Keywordsattitude Clothing emerging-market consumers intention mediation perceived risks

JEL Classification M10

Full Article

1. Introduction

The total sales value of the online retail sector in South Africa was estimated at around 30.2 billion rand in 2020, with the projection for the total online retail expected at around R42 billion in 2021 (Engineeringnews, 2021). In emerging markets, substantial growth in online shopping has been witnessed (Do, Nguyen and Nguyen, 2019, p. 1). Emerging market-consumers in South African townships and informal settlements are vital to the online shopping industry because these markets represent billions of rand in consumer spending power. However, there is very limited research available to help marketers understand where and what these consumers spend their money on, what affects their shopping behaviour, and their preferred payment methods and forms of marketing communication messages (Rogerwilco, 2021, p. 1). Online retailers in this country have been in operation for at least two decades, with Kalahari.com, one of the initial online retailers, having launched in 1998. From the vantage point of 2023, Takealot.com is the most popular online retailer, while other prominent players are mainly large traditional retailers that provide alternative outlets for online sales (businesstech.co.za, 2022; Goga, Paelo and Nyamwena 2019, p. 5). Social media marketplaces such as Facebook Marketplace have grown in popularity (businesstech.co.za, 2022). Additionally, small businesses can easily market their goods and target particular customer demographics with the help of social media and search engine advertising (XtraSpace, 2022). The growth of the South African online shopping industry is still, however, limited by a number of issues, including high data costs, poor infrastructure, high delivery costs (Goga et al., 2019, p. 2), a lack of standardised residential address systems, security concerns, and inefficient inventory management (XtraSpace, 2022).

A variety of product categories are sold online in South Africa, including food, furniture, clothing and footwear, electronics, toys, movies, alcohol, flowers, cars, houses and accessories such as watches, jewellery and sunglasses. Euromonitor (2017) identified electronics, television sets, fashion and clothing as being among the fastest-growing consumer categories. Bizcommunity (2018) identified clothing as the most popular online shopping category in South Africa, accounting for 53 per cent of all purchases, followed by entertainment/education (51%), and tickets (51%). Regardless of the growth of online shopping in South Africa, consumers nevertheless perceive some degree of risk when shopping online for clothing. The above statement is confirmed by a study conducted by Pentz, du Preez and Swiegers (2020a), in which it was observed that experienced South African online consumers perceived psychological and social risk when purchasing clothing online, whereas inexperienced South African online consumers perceived considerable financial and social risk when purchasing clothing online.

Online shopping is a business-to-consumer (B2C) form of e-commerce activity (Sheikh and Basti, 2015, p. 76; Statista, 2019) which has reshaped the retail industry by providing a platform that facilitates the process of purchasing goods and services through the internet (Malapane, 2019, p. 1; Singh and Rana, 2018, p. 27). Online shopping is convenient, providing consumers with a wide variety of products and services (Tanadi, Samadi and Gharleghi, 2015, p. 226; Tandon, Kiran and Sah, 2018, p. 58), anywhere and at any time (Arora and Sahney, 2018, p. 1040). Despite the benefits of online shopping, however, several studies have identified perceived risk as a factor preventing consumers from completing their purchases (Hong, 2015, p. 25; Hsieh and Tsao, 2014, p. 24; Wolny and Charoensuksai, 2014, p. 324), particularly in the South African consumer market (Malapane, 2019; Makhitha and Ngobeni, 2021b; Mapande and Appiah, 2018).

Studies investigating perceived risk in respect of online shopping behaviour have been conducted by researchers from around the world (Bhatti, Saad and Gbadebo, 2018; Chaturvedi, Gupta and Hada, 2016; Farhana, Khan and Noor, 2017; Mosunmola, Omotayo and Mayowa, 2018; Tandon et al., 2018). Existing studies have determined which risk factors influence consumers’ attitudes towards online shopping (Aghekyan-Simonian, Forsythe, Kwon and Chattaraman, 2012; Ariffin, Mohan and Goh, 2018; Nawi, Mamun, Binti Hamsani and Muhayiddin, 2019). There are, however, inconsistencies in the findings, with some studies measuring general perceived risk and others concentrating on a specific type of risk. Marza, Idris and Abror (2019, pp. 594) state that more research is needed to examine perceived risk in different contexts and categories, as the outcomes could differ between various product levels, types and individuals. Bhatti et al., (2018) concur and suggest that more research is needed to investigate perceived risk factors concerning purchasing behaviour in developing countries. This suggests that online retailers may be able to adopt a variety of strategies to reduce the perceived risks associated with online shopping depending on the context, product type, and product level.

Statistics demonstrate that in South Africa, the least-purchased items in online shopping platforms are products like clothing, furniture, and accessories as opposed to food and beverages, tickets, accessories, and digital entertainment (Payflex, 2022). Studies examining perceived risks associated with buying clothing online have been conducted in South Africa (Maziriri and Chuchu, 2017; Pentz, et al., 2020a; Swiegers, 2018). Several studies have also found that the perceived risk that deters consumers from successfully completing online clothing shopping transactions originates in their inability to physically examine products (Farhana et al., 2017, p. 225; Tanadi et al., 2015, p. 227), and visualise fit (Hilken, Heller, Chylinski, Keeling, Mahr and de Ruyter, 2018, p. 510; Hong and Yi, 2012, p. 1306), and online distrust stemming from concerns relating to factors ranging from privacy to security (Arora and Sahney, 2018, p. 1040). This is because in the online consumer decision-making process, the price of a product is considered a substantial factor influencing purchasing (Pappas, 2016, p. 100), which implies that consumers perceive more risk when the price of a product is too high. The reason for this is that expensive products require extended problem-solving, which affects the decision-making process (Wolny and Charoensuksai, 2014, p. 319). Thus, it is important to determine the risk factors that affect consumers' decision- making when buying highly priced products like clothing online, as well as how those risk factors could be mediated to promote more online shopping behaviour.

A number of studies have tested different factors that can be used to mitigate risk in online shopping: website quality (Hsieh and Tsao, 2014), trust (Bhattacharya, Sharma and Gupta, 2021; Lavuri, Jindal, and Akram, 2022; Qalati, Vela, Li, Dakhan, Hong Thuy, and Merani, 2021), attitude (Bhatti et al., 2018; Tran and Nguyen, 2022), e-commerce experience (Mofokeng, 2021), demographics (Makhitha and Ngobeni, 2021a), usefulness and ease of use (Mutahar, Alam, Daud, Alam, Thurasamy, Isaac, and Alam, 2018), brand awareness (Rahmi, Ilyas, Tamsah and Munir, 2022), and COVID-19 (Toska, Zeqiri, Ramadani and Ribeiro-Navarrete (2022). Although studies have been conducted testing the mediation effect of attitude on the relationship between perceived risks and online shopping intention, some were investigated from a developed country perspective. Studies that tested this relationship from the perspective of developing nations were conducted in countries outside Africa, and specifically outside South Africa (Bhatti et al., 2018; Tran and Nguyen, 2022). Kaur and Thakur (2021) concluded that emerging countries differ regarding various aspects, suggesting that attitude and perceived risk factors in online shopping differ in different emerging markets.

Smolian (2020) argues the need to determine consumer attitude in online shopping, stating that consumer attitude towards online shopping is determined by their level of trust and the fact that perceived risk is experienced during online shopping. Bhattacharya et al., (2021) conclude that consumer attitude towards online shopping and intention to engage in online shopping differ depending on the country in question. It was considered necessary to determine whether attitude mediates the relationship between perceived risk and consumer intention to shop online in the case of emerging-market consumers, since Bhatti et al., (2018) argue that perceived risk must be moderated by certain factors so as to reduce negative impact in online shopping. Therefore, this study will answer the following research question: Does attitude mediate the relationship between perceived risks and online shopping intention? The study therefore investigates the perceived risk factors influencing the attitudes and online shopping intentions of emerging consumers in South Africa in respect of clothing products as well as the mediation role of attitude on the relationship between perceived risk factors and online shopping intention. Since an individual’s intent to act may not always be realised due to various constraints (Samaradiwakara and Gunawardena, 2014, p. 28), consumers' attitudes and purchase intentions were explored. The following research objectives were thus formulated to address the above research question:

- To determine the risk factors that influence emerging-market consumers’ attitude to shop online for clothing.

- To determine the risk factors that influence emerging-market consumers’ intentions to shop online for clothing.

- To determine the mediating effect of attitude on risk factors and online shopping intention for clothing.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Grounding for the Study

The theory of reasoned action (TRA), developed by Fishbein and Ajzen (1975), has been applied in various studies to determine consumers’ attitude and online shopping behaviour, and has been proven to be a reliable theoretical basis (Arora and Aggarwal, 2018; Bhusene, 2018; Tandon et al., 2018). The TRA posits that the behaviour of an individual is an outcome of a behavioural intention, and that a behavioural intention is dictated by an individual’s attitude and subjective norms towards a behaviour (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975).

Behavioural intention is the cognitive reflection of an individual’s willingness to engage in a particular behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). At the same time, a subjective norm refers to that person’s perception of what the social group to which they belong thinks about whether or not the behaviour should be engaged in (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975). Whereas attitude is defined as an individual’s feelings towards carrying out a particular behaviour (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975), it is also a positive or negative appraisal of their behaviour. Consequently, perceived risk represents the consumer’s perception that certain negative effects will result from their purchasing of a product (Pathak and Pathak, 2017). Therefore, the TRA provides a strong theoretical grounding for investigating the perceived risk factors influencing the attitudes of emerging-market consumers towards online shopping.

2.2 Perceived Risk in Online Shopping

Perceived risk is an important factor affecting consumer decision-making in an online shopping environment (Pappas, 2016; Hong and Yi, 2012). Pham and Ho (2015) state that perceived risk in that context refers to the subjective expectation of loss or sacrifice associated with using an electronic platform. The above statement implies that during the online shopping process, consumers who purchase clothing products will focus on minimising the probability of loss and maximising the value of the purchase. Ariffin et al., (2018) state that perceived risk has an influence on consumer attitudes, with Featherman and Wells (2010) having classified online perceived risk into six dimensions, namely financial, psychological, performance, time, social and privacy risks. According to Canguende-Valentim (2022, pp. 316), social and financial risk have an impact on consumers’ attitudes and intention to purchase luxury goods. Koay (2018, p. 498) highlights that social and performance (product) risk are two risk factors that affect consumers’ intention to purchase luxury items, while a study by Khan, Razzaque and Hazrul (2017) reported that performance risk, financial risk, time risk and social risk have a negative influence on consumers’ purchase intention in respect of luxury goods. Similar to buying clothing online, luxury goods are pricey, and demand extended problem-solving; thus, the study investigated five online perceived risk factors as reported by Khan et al., (2017), namely financial, product, time/convenience, social and privacy risks.

Perceived Financial Risk

Financial risk is the potential monetary loss that can occur during the purchasing process (Ilmudeen, 2014). This risk increases when consumers shop online, as the transactional nature of such shopping requires consumers to pay for products and services in advance, without physical evaluation and immediate exchange. To mitigate the risk, most online stores have added an additional payment method, which allows consumers to place orders online and make the payment on delivery. Nevertheless, financial risk still deters onsumers from purchasing online. Financial risk was found to be the most prominent perceived risk factor in the South African online shopping market (Malapane, 2019, p. 1). According to Wai, Dastane, Johari and Ismail (2019), financial risk has a negative yet insignificant effect on online shopping behaviour, while Ariffin et al., (2018) established that financial risk has a signi?cant negative in?uence on consumers’ online purchase intention. Furthermore, Hsu and Luan (2017) found financial risk to have a significant negative influence on consumer attitude. However, these findings contradict those of a study conducted by Han and Kim (2017), which explored consumers’ hesitation and perceived risk in online shopping and concluded ?nancial risk to be positively related to trust and purchase intention, suggesting that consumers felt financially secure about shopping online.

Siu and Ismail (2022) reported that perceived financial risk negatively affects online purchase intention, while Pentz et al., (2020a) observe that the purchase intention of inexperienced online shoppers is influenced by perceived financial risk. This bears out the work of Swiegers (2018), who also reported that inexperienced online consumers are affected by perceived financial risks. Therefore, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1: Perceived financial risk has a significant and positive influence on the attitude of emerging-market consumers towards online shopping for clothing.

H2: Perceived financial risk has a significant and positive influence on the intention of emerging-market consumers to shop online for clothing.

Perceived Time/Convenience Risk

Purchasing products online causes consumers a certain degree of discomfort, as products may not be shipped or may be damaged in the distribution process, delays could occur, or the products may be delivered to the incorrect destination. All of these potential obstacles are related to delivery and time risk. Delivery risk is the potential loss consumers might incur as a result of delayed product deliveries, non-delivery, or the delivery of damaged products (Tanadi et al., 2015, p. 227), whereas time risk refers to time and effort spent navigating the website, completing the purchase, waiting for delivery, and returning the product in the case of dissatisfaction (Aghekyan-Simonian et al., 2012, p. 327). Therefore, convenience risk can be defined as the risk associated with products being delivered to the wrong consumer, being damaged or being misplaced during transportation (Bhatti et al., 2019).

The existing body of research, however, reflects opposing views regarding the impact of time risk. According to Cherrett, Dickinson, McLeod, Sit, Bailey and Whittle (2017), time risk is not a significant barrier to consumers’ intentions to purchase online. By contrast, Wai et al., (2019) deem time risk to exert a significant negative influence on consumers’ online shopping intention. Additionally, a study conducted by Hsu and Luan (2017) found time risk to have a negative influence on consumers’ attitude toward online shopping, as confirmed by a number of researchers (Ariffin et al., 2014; Tanadi et al., 2015; Tariq, Bashir and Shad, 2016). Furthermore, consumers' attitudes regarding online shopping in South Africa were found to be negatively influenced by delivery risk (Makhitha and Ngobeni, 2019b, p. 7). Pentz et al., (2020b) and Tham, Dastane, Johari and Ismail (2019) reported that inexperienced online shoppers are influenced by product risk, Against the above discussion, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H3: Perceived convenience risk has a significant and positive influence on the attitude of emerging-market consumers towards online shopping for clothing.

H4: Perceived convenience risk has a significant and positive influence on the intention of emerging-market consumers to shop online for clothing.

Perceived Product Risk

Consumers who shop online experience a certain level of uncertainty and insecurity arising from a sense that they have minimum control over the outcome of their virtual purchase because they are not able to physically touch and feel the product (Farhana et al, 2017, p. 225). This insecurity and uncertainty are linked to the risk associated with the product, and particularly its performance (Tariq et al., 2016, p. 96). Product risk refers to the loss consumers feel when the product fails to meet or exceed their expectations (Tandon et al., 2018, p. 68). According to Tariq et al (2016, pp. 98), product risk has no significant effect on consumers’ attitudes towards online shopping behaviour. Several studies have, however, found product risk to adversely affect the intention of consumers to purchase online (Aghekyan-Simonian et al., 2012, p. 329; Han and Kim, 2017, p. 24). This is consistent with studies that found product risk to have a negative influence on consumers’ attitudes towards online shopping (Bhatti et al., 2018, p. 7; Hsu and Luan, 2017, p. 25).

Furthermore, product risk was revealed to have an effect on the attitudes of South African consumers regarding online shopping (Makhitha and Ngobeni, 2021, p. 7). Siu and Ismail (2022) found perceived risk to affect online purchase intention negatively, while Tham et al., (2019) reported a positive impact.

H5: Perceived product risk has a significant and positive influence on the attitude of emerging-market consumers towards online shopping for clothing.

H6: Perceived product risk has a significant and positive influence on the intention of emerging-market consumers to shop online for clothing.

Perceived Social Risk

Consumers who anticipate possible disapproval on the part of their social group of an online purchasing decision are more likely to discard their online carts to avoid criticism from those groups. Online shopping carts are in some instances discarded because consumers seek feedback from their families, friends, and opinion leaders so as to minimise negative opinions regarding their purchasing behaviour. Social factors are recognised as being an important influence on consumer attitudes and online buying behaviour (Singh and Kashyap, 2017). Social risk in this context refers to the probability of a consumer’s peer group forming a negative perception about the purchasing behaviour (Shang, Pei and Jin, 2017). Pentz et al., (2020b) investigated the impact of perceived risk factors on online consumers' shopping behaviour and concluded that both experienced and inexperienced South African online shoppers perceive social risk when shopping for clothing online. Hsu and Luan (2017), who examinedconsumers' attitudes and purchase intentions in Vietnam, found a negative relationship between social risk and online shopping attitude, which suggests that those consumers are not concerned about the social risk of purchasing online. Of importance is the fact that Han and Kim (2017) found social risk to adversely affect customers’ intention to purchase online. Furthermore, Maziriri and Chuchu (2017) found perceived social risk to be a factor influencing the online shopping behaviour of South African consumers. Pentz et al., (2020b) also mention that social risk influences the online purchase intention of inexperienced shoppers. Based on the above evidence, it can be postulated that:

H7: Perceived social risk has a significant and positive influence on the attitude of emerging-market consumers towards online shopping for clothing.

H8: Perceived social risk has a significant and positive influence on the intention of emerging-market consumers to shop online for clothing.

Perceived Security Risk

Consumers avoid purchasing products online because most online retailers request personal information before a purchase can be made. In turn, privacy and security issues arise during the check-out process, leading to customers discarding their shopping carts. The use of online payment systems creates a certain degree of insecurity for consumers who shop online (Tanadi et al., 2015), as they fear that their personal and financial information will be misused (Thakur and Srivastava, 2015; Yadav, Sharma and Tarhini, 2016). Privacy and security risks have been reported as factors commonly affecting the online purchasing behaviour of consumers (Farhana et al., 2017; Hong and Yi, 2012; Rahman, Islam, Esha, Sultana, Chakravorty and Molnar, 2018). A correlation has also been found between perceived security risk, perceived privacy risk, and consumers’ attitudes toward engaging in online shopping (Jun and Jaafar, 2011). Privacy risk is defined as the fears consumers have about the privacy of their personal data and credit card details, which may be misused by the seller (Ariffin et al., 2014), whereas security risk refers to concerns about monetary loss through the use of online payment systems (Thakur and Srivastava, 2015). Dai and Chen (2015) report that security issues have a negative effect on the purchasing intentions of customers on online shopping platforms. The above-mentioned finding is consistent with past studies, which found privacy risk to have a significant negative influence on consumers’ attitudes towards online shopping behaviour (Hsu and Luan, 2017; Orubu, 2016). Moeti, Mokwena and Malebana, (2021) support the finding by Dai and Chen (2015) that security issues have a negative influence on online consumers’ purchase intention.

H9: Perceived security risk has a significant and positive on the attitude of emerging-market consumers towards online shopping for clothing.

H10: Perceived security risk has a significant and positive influence on emerging-market consumers’ intention to shop online for clothing.

2.3. Consumer Attitude as Mediator: Perceived Risk and Intention to Shop Online

Consumer decision-making is influenced by attitudes, which are formed through assessments of the outcomes of a particular action (Reyes-Mercado, Karthik, Mishra and Rajagopal, 2017, p. 330). As such, consumer attitudes play a critical role in shaping the impact of perceived risks on consumer intents, influencing the extent to which perceived risks affect their decision to engage in online shopping. Jiang, Qin, Gao and Gossage (2022) support this statement by stating that perceived risks operate differently depending on the buying circumstances, which requires that different mediation factors be used.

One of the mediators of perceived risk and consumer purchase intention has been identified as attitude (Liebenberg, Benade, and Ellis, 2018). Tyrvainen and Karjaluoto (2022) identified attitude as a key factor mediating between determinants and intents. Existing research has also demonstrated that, in online shopping, consumer attitude mediates the influence of perceived risk and purchase intention (Lavuri et al., 2022; Siu and Ismail, 2022; Tarawneh et al., 2021). Putra, Rochman, and Noermijati (2017, pp. 477), for example, reported that the relationship between purchasing intention and consumer attitudes is negative and insignificant, implying that an increase in risk factors will not have a significant impact on purchasing intention reduction through consumer attitudes, whereas Bhatti et al., (2018) concluded that attitude significantly moderates the effect of convenience/time risk.

In other contexts of adoption, such as tourism, it was discovered that attitude had no mediation effect between perceived risks and behavioural intention (Hasan, Ray and Neela, 2021, p. 963). There was no evidence of a mediation influence of attitude in the automotive sector between risk and adoption intention of electronic vehicles (Jaiswal, Kaushal, Kant and Singh, 2021, p. 1). In the online banking sector, attitude was found to fully mediate the relationship between perceived financial cost (financial risk) and behavioural intention (Shanmugam, Savarimuthu and Wen, 2014, p. 240). In line with the evidence cited, it was proposed that attitude, which describes an individual's positive or negative appraisal of a behaviour (Arora and Aggarwal, 2018, p. 96), function as a mediator between perceived risk variables and purchase intention.

Therefore, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H11: Consumer attitude has a significant and positive influence on emerging-market consumers’ intention to shop online for clothing.

H12: Consumer attitude mediates the relationship between perceived financial risk and the intention of emerging-market consumers to shop online for clothing.

H13: Consumer attitude mediates the relationship between perceived convenience risk and emerging-market consumers’ intention to shop online for clothing.

H14: Consumer attitude mediates the relationship between perceived product risk and the intention of emerging-market consumers to shop online for clothing.

H15: Consumer attitude mediates the relationship between perceived social risk and emerging-market consumers’ intention to shop online for clothing.

H16: Consumer attitude mediates the relationship between perceived security risk and emerging-market consumers’ intention to shop online for clothing.

2.4. Purchase Intention

Consumer decision-making is influenced by attitudes, which are formed through assessments of the outcomes of a particular action (Reyes-Mercado et al., 2017, p. 330). As such, a consumer will be more inclined to purchase products and services online if they have a positive attitude towards online shopping. Purchase intention describes a consumer's willingness to purchase an item or service (Stravinskiene, Dovaliene and Ambrazeviciute, 2013, p. 765). The term "purchase intention" in an online setting refers to a consumer's inclination to purchase a good or service online (Tjhin and Permatasari, 2019, p. 5). In attempting to mitigate various external factors that deter consumers from shopping online, it is imperative for businesses to favourably impact consumers' perceptions.

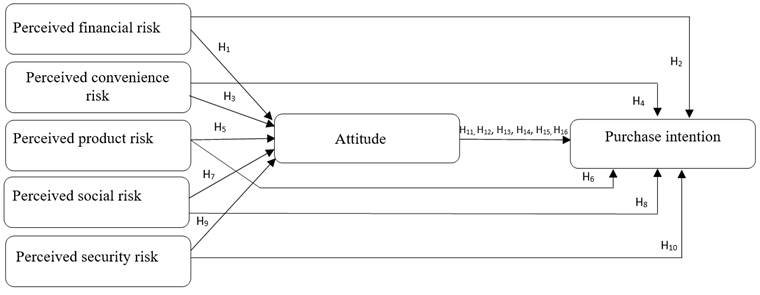

Figure 1 shows the conceptual model for the study. The figure shows five risk factors that could influence the attitude of emerging consumers towards online clothing shopping.

Figure 1. Conceptual model

3. Research Methods and Design

3.1. Study Design and Sample

A quantitative research method was adopted for the study; this was deemed appropriate, as quantitative research approaches have been widely adopted by researchers investigating online shopping (Orubu 2016; Tandon et al., 2018). It was therefore identified as suitable for achieving the main objective of the study reported on here, which was to determine the influence of perceived risk as a factor on consumer attitudes and intentions to shop online for clothing as these related to emerging-market consumers.

The study population comprised emerging-market consumers residing in Soweto township, who purchase clothing products. The market, consisting mainly of black consumers, is regarded as the market with high buying power. Its population exceeds two million people with a consumption value of R34 billion ($1.8 billion) (Bizcommunity, 2019). Consumers living in this township have a per capita consumption of R18 300 per person and varying social and class divisions (New York Times, 2019). They have access to smartphones, which are used mainly for online shopping instead of computers; however, internet penetration is lower than the rest of South Africa (GFK, 2017). The targeted population sample consisted of those shoppers who had in the past shopped online.

3.2. Data Collection and Research Instrument

A self-completion questionnaire was used for the survey, which was necessary since data was collected online. A survey questionnaire was used in existing studies on perceived risk and was deemed appropriate for this study to achieve the set objectives. The questionnaire was designed on the basis of prior research studies investigating online shopping, with a specific focus on those that investigated risk in online shopping. The following sources were drawn on during the questionnaire design stage in order to formulate questionnaire items: perceived finance risk (Ariffin et al., 2014; Hsu and Luan 2017; Masoud, 2013); perceived convenience risk (Bhatti et al., 2018; Pi and Sangruang, 2011), product risk (Aghekyan-Simonian et al., 2012; Ariffin et al., 2018; Hsieh and Tsao, 2014; Javadi, Dolatabadi, Nourbakhsh, Poursaeedi and Asadollahi, 2012; Tandon et al., 2018; Tariq et al., 2016; Thakur and Srivastava, 2015; Vijayasarathy, 2004), perceived security risk (Ariffin et al., 2018; Hsieh and Tsao, 2014; Thakur and Srivastava, 2015) perceived social risk (Pi and Sangruang, 2011; Thakur and Srivastava, 2015) and perceived security risk (Hong and Yi, 2012; Javadi et al., 2012; Tandon et al., 2018; Tariq et al., 2016). There were 32 items measuring risk in online shopping, with seven measuring perceived financial risk, eight measuring perceived convenience risk, six measuring perceived product risk, four measuring perceived social risk and four measuring perceived security risk. The questionnaire consisted of 13 demographic questions and 21 statements linked to risk factors influencing consumers when shopping online. There were three items linked to intention to shop online. The questions investigating perceived risk factors were measured using a five-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating “highly disagree” and 5 “highly agree”. The researcher sought ethical clearance from the Department of Marketing and Retail Management at Unisa prior to conducting the study.

Data was collected by an independent specialist research company during June 2021. The research company had access to over 3 000 consumers residing in Soweto and who shop online. The online link from where respondents could access the questionnaire was conveniently distributed via emails and WhatsApp to all the consumers in the database. In total, 290 questionnaires were completed online by the respondents; however, over 80 of these questionnaires were either incomplete or did not meet the survey criteria and were therefore discarded, resulting in 210 fully completed questionnaires. Since the plan was to source data from 300 participants, an additional 90 participants were sourced by field workers who visited the township and conveniently intercepted people meeting the qualifying criteria, e.g., that they shop for clothing online and also that they reside in the township. The sample size matched those of other studies investigating online shopping (Muda, Mohd and Hassan, 2016).

3.3. Analysis of Data

The SAS JMP version 15 for Mac and the R language version 3.5.2 were used to analyse the data. The following statistical tests were conducted to achieve the objectives of the study: descriptive analyses (e.g., mean and standard deviation), exploratory factor analysis, and structural equation modelling (SEM). SEM is used mostly to test conceptual models developed to achieve the objectives of a study, which is why it was selected for this study. For example, Kaplan, (2001) states that when SEM is used, researchers evaluate the model fit first and, if found fit, they then evaluate individual path. Since the model was conceptualised in this study, it was necessary to use SEM to test the hypothesis formulated.

4. Results and Findings

This section presents the results of the study, starting with the profile of the respondents.

4.1. Demographics of the Respondents

Over 70 per cent of the population (73.6%, n=221) was female, and 25.6% (n=77) male. Of the respondents, 42 per cent (n=126) were between the ages of 18 and 24, 28 per cent (n=84) were between the ages of 18 and 29 (n=84), and 22 per cent (n=65) were between the ages of 30 and 40. Most of the respondents (72%, n=216) were unmarried. Over one third of the respondents had post-school qualifications in the form of a degree (38%, n=115), followed by those with Grade 12 (37%, n=110) and those holding a post-school qualification in the form of a diploma/certificate (23%, n=68). Regarding monthly income, most of the respondents earned between R5 000 and R7 500 (62%, n=186), with only 9 per cent (n=27) earning above R20 000.

4.2. Validity and Reliability

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to determine whether the individual risk factors loaded onto the constructs as intended in the questionnaire. EFA also determined the construct validity of the study. The communalities ranged from 0.57 to 0.88, which is higher than the minimum threshold of 0.2 proposed by Child (2006). Constructs were developed from the existing questionnaire, as reported in the data collection instrument section, to achieve construct validity.

To assess the reliability of the different constructs in the questionnaire, the Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficient was calculated. A Cronbach alpha of 0.96 was achieved for all the constructs: 0.97 (perceived financial risk), 0.94 (perceived convenience risk), 0.95 (perceived product risk), 0.94 (perceived social risk) and 0.90 (perceived security risk). The Cronbach’s alpha for the attitude construct was 0.97. As proposed by Malhotra (2010), a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of less than 0.50 is deemed unacceptable; those between 0.50 and 0.69 are considered adequate, and those above 0.70 are regarded as acceptable. Due to the score for security risk being unacceptable, this was not used for further analysis.

4.3. Factor Analysis

An exploratory principal factor analysis with axis factoring, in SAS JMP version 15, was conducted on all the perceived risk factors with the purpose of determining how well they would group together to a factor. EFA with axis factoring was considered appropriate for the correlation patterns between the questions used to determine the respondents’ perceptions of online shopping risks in South Africa. Principal axis factoring was used to extract the risk factors, followed by a quartimin (oblique) rotation. Five factors which had eigenvalues greater than 1 were identified, with a total variance of 78.48 per cent (see Table 1).

According to Stevens (in Field and Miles, 2010, p. 557), a factor loading of 0.36 is accepted for a sample of 200. For this study, items loading 0.40 or greater were considered for further analysis, since the population size was 300. Factor 1, “perceived financial risk”, loaded nine items. The eigenvalue for this factor was 15.30, with a percentage of variance of 36.56. One of the items that loaded in this factor was more relevant to security. The factor had a mean score (M) of 3.53 and a standard deviation (SD) of 1.00. The next factor, “perceived convenience risk”, loaded eight items and had an M score of 3.32 and an SD of 1.02. The eigenvalue for this factor was 3.35, with a percentage of variance of 35.35. The first and second factors loaded most of the items (nine and eight items respectively). The third factor, “perceived product risk”, loaded six items, with an M score of 3.70, the highest of all the factors, showing product to be the most important factor for consumers when shopping online. The SD for this factor was 1.05, which is also higher than for other factors, showing that the respondents had varied perceptions regarding the importance of this when shopping online. The eigenvalue and the percentage of variance were 2.25 and 33.06 respectively. Loaded onto the fourth factor, “perceived social risk”, were four items, an M score of 2.82 and an SD of 1.12. The SD for this factor was higher than for all the other factors, which indicates a difference of opinion among the respondents regarding its importance in online shopping, as indicated by Field and Miles (2010, pp. 37). The last factor, “perceived security risk”, loaded four items with an M score of 2.63 and an SD of 1.00. The eigenvalue for this factor was 1.26, and the percentage of variance was 21.70. Attitude had an M score of 3.35 with an SD of 1.14, higher than for other variables, which indicates differences among the respondents’ attitude towards online shopping. According to Field and Miles (2010, pp. 37), an SD closer to 1 indicates variations in the responses.

Table 1. Factor analysis

| Factor 1: Perceived financial risk | Factor 2: Perceived convenience risk | Factor 3: Perceived product risk | Factor 4: Perceived social risk | Factor 5: Perceived security risk | Attitude | |

| My credit card number may not be secure | 0.91 | -0.03 | 0.05 | -0.03 | -0.01 | |

| I may not get what I want | 0.88 | 0.05 | 0.05 | -0.06 | 0.00 | |

| Can’t trust the online company | 0.88 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | -0.05 | |

| Might be overcharged | 0.86 | -0.01 | 0.07 | 0.03 | -0.06 | |

| My personal information may not be kept safe | 0.85 | 0.03 | -0.00 | -0.02 | 0.10 | |

| May not get the product | 0.78 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.02 | -0.01 | |

| May purchase something by accident | 0.72 | 0.04 | -0.02 | 0.09 | 0.02 | |

| The online shopping company may disclose my personal information | 0.47 | -0.01 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.31 | |

| Information about the online shopping company may be insufficient | 0.46 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.39 | |

| The online vendor makes accurate promises about the delivery of the product | -0.09 | 0.88 | -0.04 | 0.02 | 0.11 | |

| Using the Internet for my apparel/clothing shopping enables me to accomplish tasks more quickly | -0.08 | 0.85 | -0.03 | -0.01 | 0.09 | |

| If I shop online, I have to wait until the product arrives | -0.03 | 0.80 | 0.18 | -0.17 | 0.09 | |

| I feel that it will be difficult settling disputes when I shop online | 0.12 | 0.79 | 0.09 | -0.01 | -0.10 | |

| It is not easy to cancel orders when shopping online | 0.06 | 0.78 | 0.03 | 0.07 | -0.05 | |

| It is difficult to find appropriate websites | 0.20 | 0.71 | 0.01 | 0.08 | -0.05 | |

| Pictures of merchandise on the website take too long to come up | 0.10 | 0.65 | -0.06 | 0.27 | -0.00 | |

| Finding the right product through online shopping is difficult | 0.11 | 0.61 | 0.08 | 0.22 | -0.09 | |

| I am unable to touch and feel the item | -0.01 | -0.04 | 0.95 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| I must pay for shipping and handling costs | -0.03 | -0.05 | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.07 | |

| I must wait for merchandise to be delivered | -0.05 | 0.02 | 0.88 | -0.00 | 0.05 | |

| Finding the right size may be a problem with clothes | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.86 | -0.02 | -0.04 | |

| I cannot try on clothing online | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.85 | -0.00 | -0.03 | |

| I cannot examine the actual product | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.73 | 0.04 | -0.03 | |

| Online shopping may result in others thinking less of me | 0.02 | 0.05 | -0.02 | 0.91 | 0.01 | |

| The purchased product may result in disapproval from my family | -0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.89 | 0.01 | |

| Online shopping may affect my image among people around me | 0.05 | -0.02 | 0.03 | 0.86 | 0.05 | |

| Online products may not be recognised by relatives and friends | -0.03 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.78 | 0.07 | |

| I feel safe in my transactions with this website | -0.03 | -0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.86 | |

| I feel I can trust this website | -0.07 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.83 | |

| I feel safe to use my credit or debit card when shopping online | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.75 | |

| The website has adequate security features | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.01 | -0.08 | 0.62 | |

| Total percentage of variance | 36.56 | 33.36 | 33.06 | 23.39 | 21.70 | |

| Eigenvalues | 15.30 | 3.35 | 2.25 | 2.15 | 1.26 | |

| Mean score | 3.53 | 3.32 | 3.70 | 2.82 | 2.63 | 3.35 |

| Standard deviation (SD) | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.05 | 1.12 | 1.00 | 1.14 |

4.4. Model Testing

The model was tested using SEM, the lavaan version 0.6–1 (Rosseel 2012) in R version 3.5.2 for structural equation modelling (R Core Team 2018). To produce the test statistics, a maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (maximum likelihood mean (MLM)), was used. The MLM chi-square test statistic is also referred to as the Satorra-Bentler chi-square with robust standard errors. The latent factors were standardised, allowing for free estimation of all factor loadings – the R version 3.5.2 with the lavaan library. The purpose of this phase was to assess causative relationships among latent constructs (Nusair and Hua, 2010). The chi-square value over degree of freedom, normed fit index (NFI), incremental fit index (IFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI) and standard root mean residual (root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)) were the indices used to measure the model fit of the study. Since the model had five factors, they were all tested to determine their influence on attitude towards online shopping. Table 2 shows the results of model fit testing. According to Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham (2006), in order to show model fit, the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), CFI, TLI, IFI, relative fit index (RFI) and NFI must be greater than or equal to 0.9; however, a value greater than 0.8 can marginally be accepted. As is evident in Table 2, there was a good model fit with the following indices: a chi-square = 1200.786, degree of freedom = 686; p = 0.000, the relative chi-square = 1.45, RMSEA of 0.054 90% CI (0.043, 0.059), SRMSR = 0.059, CFI = 0.976 (robust) and TLI of 0.973 (robust). The 90% confidence interval for the RMSEA statistics ranged from 0.043 to 0.059, meaning that it was possible that the population RMSEA statistic might be as low as 0.043 or as high as 0.059. The RMSEA of 0.051 was attained, as supported by Steiger (2007), signifying the model fit. According to Hu and Bentler (1999), a cut-off value close to 0.08 for SRMR signifies a good fit between the model and the data under observation. An SRMSR of 0.059 was attained in the study. The structural model is shown with standardised coefficients of the five perceived risk factors (financial, convenience, product, social and security risk) that were tested to determine whether they influenced consumers’ attitudes towards online shopping (see Table 2).

Table 2. Model fit indices

| Model fit index | Value indicator |

| Chi-square (X2/DF) | 1.45 |

| GFI (goodness-of-fit) | 0.8 |

| CFI (comparative fit index) | 0.976 |

| TLI (Tucker-Lewis index) | 0.973 |

| IFI (incremental fit index) | 0.976 |

| RFI (relative fit index) | 0.92 |

| NFI (norm fit index) | 0.927 |

| RMSEA root (mean square error of approximation) | 0.051 CI 90% |

4.5. Hypothesis Testing Results

The statistical analysis involved a regression analysis being performed as part of the structural section of the SEM model. The purpose of the first regression was to determine the influence of perceived financial risk (PFR), perceived convenience risk (PCR), perceived product risk (PPR), perceived social risk (PSR) and perceived security risk (PSecR) on attitudes towards online shopping. To test the statistical significance in the SEM model, the z-values with Wald tests were used.

The perceived convenience risk (PCR) factors had a more marked effect on attitude towards online shopping, with a beta coefficient of 0.379 (z = 3.241); Therefore, H3 is supported. This was followed by perceived financial risk (PFR), with a negative beta coefficient of -0.228 (z = -2.262); therefore, H1 is also supported. The perceived security risk (PSecR) had a negative effect on attitude towards online shopping, with a beta coefficient of –0.239 and a z value of -2.005, which shows that the hypothesis was not significant (see Table 3); therefore, H9 is supported. Perceived product risk (PPR), p=0.251, H5 is rejected and perceived social risk (PSR), p=0.634 had no effect on attitude towards online shopping; therefore, H7 is rejected.

Table 3. Regression model – risk factors and attitude

| Intention | Hypothesis | Beta coefficient | Std error | z-value | p-value | Std. coefficient | Decision |

| PFR à Att | H1 | -0.228 | 0.101 | -2.262 | 0.024 | -0.228 | Supported |

| PCRà Att | H3 | 0.379 | 0.117 | 3.241 | 0.001 | 0.379 | Supported |

| PPR à Att | H5 | 0.126 | 0.110 | 1.147 | 0.251 | 0.126 | Rejected |

| PSR à Att | H7 | -0.040 | 0.083 | -0.476 | 0.634 | -0.040 | Rejected |

| PSecR à Att | H9 | -0.239 | 0.119 | -2.005 | 0.045 | -0.239 | Supported |

None of the perceived risks influence consumer intention to shop online and are all rejected, as shown by the p values higher than 0.005-perceived financial risk (PFR)( p= 0.721, H2), perceived convenience risk (PCR) ( p= 0.473, H4), perceived product risk (PPR) (p=0.585, H6 ), perceived social risk (PSR) (p= 0.205, H8 ) and perceived security risk (PSecR, (p= 0.449, H10 ). Consumer attitude towards online shopping has a significant effect on intention to shop online (p=0.000, b =0.832, H11). The results appear in Table 4 below.

Table 4: Regression model – risk factors and Intention

| Intention | Hypothesis | Beta coefficient | Std error | z-value | p-value | Std. coefficient | Decision |

| PFR àInt | H2 | 0.016 | 0.046 | 0.357 | 0.721 | 0.016 | Rejected |

| PCRàInt | H4 | 0.049 | 0.068 | 0.718 | 0.473 | 0.046 | Rejected |

| PPR àInt | H6 | 0.031 | 0.056 | 0.546 | 0.585 | 0.027 | Rejected |

| PSR àInt | H8 | -0.059 | 0.047 | -1.267 | 0.205 | -0.059 | Rejected |

| PSecR àInt | H10 | 0.049 | 0.065 | 0.756 | 0.449 | 0.034 | Rejected |

| Att à Int | H11 | 0.832 | 0.037 | 22.526 | 0.000 | 0.866 | Supported |

Table 5 below presents the results for the mediation of attitude on the relationship between perceived risks and consumer intention to adopt online shopping.

Table 5. Regression model: indirect effect

| Intention | Hypothesis | Beta coefficient | Std error | z-value | p-value | Std. coefficient | Decision |

| PFC àAtt à Int | H12 | -0.190 | 0.085 | -2.243 | 0.025 | -0.181 | Supported |

| PCR àAtt à Int | H13 | 0.316 | 0.105 | 3.006 | 0.003 | 0.299 | Supported |

| PPR àAtt à Int | H14 | 0.105 | 0.096 | 1.103 | 0.270 | 0.094 | Rejected |

| PSR àAtt à Int | H15 | -0.031 | 0.072 | -0.439 | -0.661 | -0.031 | Rejected |

| PSecR àAtt à Int | H16 | 0.199 | 0.105 | 1.906 | 0.057 | 0.140 | Supported |

The mediation test devised by Baron and Kenny (1986) was used to determine the mediation. Attitude was found to fully mediate the path relationship between PFR and intention to shop online (b = -0.190, p = 0.025); therefore, hypothesis H12 is supported. This is shown by the p-value of 0.025, which is below the required p-value of 0.05. The effect of the mediation of -0,190, is negative, showing the negative effect that attitude has on the relationship between perceive financial risk (PCR) and consumer intention to shop online. This implies that attitude negatively influences consumer intention to shop online due to perceived risk.

Attitude was found to fully mediate the path relationship between PCR and intention to shop online (b = -0.316, p = 0.003); therefore, hypothesis H13 is supported. Consumer attitude was also found to mediate the relationship between perceived convenience risk (PCR) and consumer intention to shop online (p-value = 0.03). The mediation effect of attitude on the relationship between perceived convenience risk (PCR) and consumer intention to shop online is stronger than for other perceived risk types, as shown by the high b value of 0.316, which shows the percentage of the effect that the mediation of attitude has on the relationship between perceived convenience risk (PCR) and consumer intention to shop online.

Attitude was found not to mediate a significant path relationship between PPR and intention to shop online (b = -0.105, p = 0.270); therefore, hypothesis H14 is rejected. This is due to the p-value of 0.270, which is greater than the acceptable value of 0.05.

Attitude was also found not to mediate a significant path relationship between PSR and intention to shop online (b = -0.031, p = 0.661); therefore, hypothesis H15 is rejected. This is due to the b value of 0.661, which is greater than the acceptable value of 0.05.

Attitude was found to fully mediate a significant path relationship between PSecR and intention to shop online (b = -0.199, p = 0.057); therefore, hypothesis H16 is supported. Consumer attitude was found to mediate the relationship between perceived convenience risk (PCR) and consumer intention to shop online (p-value = 0.03). The mediation effect of attitude on the relationship between PSecR and consumer intention to shop online is stronger than for other perceived risk types, as shown by the high Z values of 0.199, which shows the percentage of the effect that the mediation of attitude has on the relationship between perceived convenience risk (PCR) and consumer intention to shop online. Attitude has the second strongest effect on relationship between perceived risk, in this case, perceived security risk and consumer intention, due to the b value of 0.199.

5. Discussion

Perceived finance risk was found to have a statistically significant influence on consumers’ perceived attitude towards online shopping, but did not have an effect on online shopping intention. Attitude was found to mediate a significant path relationship between perceived finance risk and intention to shop online, which means that reducing this risk has an effect on consumer intention to shop online. It is important to note that this influence was negative, which could mean that consumers were negatively affected by finance when shopping online. These findings are supported by existing studies that report that perceived finance negatively affected consumers’ attitudes towards online shopping (Ariffin et al., 2014; Hong, Zulkiffli and Hamsani, 2019; Nawi et al., 2019) while Dai, Forsythe and Kwon (2014) identified the marginal effect of perceived finance risk on consumer online shopping intention. Although the study reported on here found finance to have less influence than perceived convenience risk, other studies have found perceived finance risk to have a low influence on attitudes towards online shopping (Hong et al, 2019). The findings of other studies also differ in this regard in that they reported the influence of perceived risk on intention to shop online (Tanadi et al., 2015). Tran and Nguyen, (2022) found attitude to mediate the effect of perceived risk on purchase intention (Tran and Nguyen, 2022), which is in support of the findings of our study and, in turn, confirms research hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 12. Hypothesis 2 could not be confirmed in this study but is supported by existing studies, proving that perceived risk influences consumer buying intention (Ariffin et al., 2018; Katta and Patro, 2017; Ha, 2020).

Perceived convenience risk had a statistically significant influence on consumers’ perceived attitudes towards online shopping, but no effect on intention to shop online. Since the influence was negative, it could mean that consumers were positively affected by convenience when shopping online. Attitude was found to mediate a significant path relationship between perceived convenience risk and intention to shop online. Therefore, hypotheses 3 and 13 have been confirmed while hypothesis 4 was not confirmed in this study. This implies that changing consumer attitude towards perceived convenience risk had an effect on their intention to shop online. Ariffin et al., (2018) found that perceived convenience risk had a positive influence on consumers’ attitudes towards online shopping, which supports the findings of our study, while Tanadi et al., (2015) reported that perceived risk influenced intention to shop online, contradicting the findings of our study. Nawi et al., (2019) reported different findings, namely that perceived convenience risk had no influence on attitudes towards online shopping. A study by Bhatti et al., (2018) found perceived convenience risk to have a greater effect on attitude towards online shopping, and that attitude moderated the relationship between perceived finance risk and online shopping intention. Although this study could not confirm hypothesis 4, it is supported by findings on existing studies (Ariffin et al., 2018; Katta and Patro, 2017; Ha, 2020). c

Perceived product risk had no statistically significant influence on consumers’ perceived attitudes towards online shopping, and did not have an effect on intention to shop online. However, the effect of perceived product risk on consumer intention to shop online is mediated by attitude. This study could not confirm hypotheses 5, 6 and 14. By contrast, Makhitha and Ngobeni (2021b), Hong et al., (2019) and Ariffin et al., (2018) confirmed product risk as having an influence on online shopping behaviour. Bhatti et al (2018) concluded that the effect of perceived product risk on intention to shop online is mediated by attitude, which shows that without the mediator, perceived product risk does not influence online shopping intention. Furthermore, Bhatti and Rahman (2019) also found that intention mediated the relationship between perceived risk and online purchase behaviour. Other studies supported the findings reported in this study, namely that perceived product risk has no significant influence on attitude towards online shopping (Tariq et al., 2016). Dai et al., (2014) reported consumer perceptions of perceived product risk as negatively influencing consumers’ online shopping intentions. Other studies also found that perceived risk influence consumer buying intention (Ariffin et al., 2018; Katta and Patro, 2017; Ha, 2020).

Perceived social risk had no statistically significant influence on consumers’ attitudes towards online shopping, and also no effect on intention to shop online. This study could not confirm hypothesis 7; however, this hypothesis is supported by Nawi et al., (2019), who found perceived social risk to have an influence on consumers’ attitudes towards online shopping. Hypothesis 8 could not be confirmed in this study and differs from that of Siu and Ismai (2022), who found social influences to affect the relationship between perceived risk and online purchase intention. The study findings did not confirm hypothesis 15, which is in contrast with a study by Zang, Qian and Song (2022) that found community interaction to partially mediate the relationship between perceived risk and repurchase intention.

Perceived security risk had a statistically significant influence on consumers’ attitude towards online shopping, but no effect on consumer intention to shop online. Attitude was found to mediate a significant path relationship between perceived security risk and intention to shop online. This study could confirm hypothesis 9 but could not confirm hypothesis10. Hypothesis 16 was also confirmed, since attitude was found to mediate the relationship between perceived security risk and attitude in online shopping. The findings of Mapande and Appiah (2018) support the findings reported on here, as do those of Keisidou, Sarigiannidis and Maditinos (2011) and Dai and Chen (2015). However, Dai et al., (2014) also concluded that perceived privacy risk does not influence consumer intention to shop online. The fact that attitude mediates the relationship between perceived risk and online shopping is supported by Bhatti and Rahman (2019), who found that intention mediates the relationship between perceived risk and online purchase behaviour.

6. Implications

The study findings show perceived financial risk, perceived convenience risk and perceived security risk to have a significant influence on attitude, with perceived product risk and perceived social risk found to have no significant influence on consumers’ attitude towards online shopping. What is interesting is that all perceived risk factors had no direct influence on consumers’ intention to shop online either. The three perceived risks – perceived finance risk, perceived convenience risk and perceived security risk – were shown to have an indirect positive effect on the intention to shop online through the mediation of attitude. The study has both theoretical and practical implications.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The study made a number of contributions to existing research. First of all, the study determined the effect of attitude on risk factors in online shopping for clothing in a particular area in South Africa. Although existing studies have determined the effect of perceived risk on consumer attitude in online shopping, none of them focused on online shopping for clothing in South Africa. Therefore, the study contributes to existing knowledge from a South African perspective, and particularly that regarding online apparel shopping. The investigation conducted also determined the effect of perceived risk factors on consumer intention to shop online. Moreover, the study adds to the existing body of knowledge in that no study thus far has determined the effect of perceived risk factors on both attitude and intention to shop online.

The study investigated the mediation by attitude of the relationship between perceived risk factors and consumers’ intention to shop online, and in doing so filled a knowledge gap in the developing nations context; previous studies conducted in this field were carried out in the context of developed countries. As was stated previously, perceived risk factors differ depending on region, as do consumer attitude and intention to shop online.

6.2. Practical Implications

The study findings have a number of practical implications for online retailers who direct their offerings at emerging-market consumers. These retailers would benefit by responding to those perceived convenience risk factors that have the greatest influence on online shopping behaviour. To mitigate risk, online clothing retailers should manage the quality of their websites by ensuring that images of the merchandise come up more quickly and are of good quality, and that the websites are easy to navigate. Images should show the products as they are, and not misrepresent their quality to consumers. E-tailers should also ensure that products are conveniently available and delivered on time, and should make it easy for consumers to complain or return merchandise should this be necessary.

To respond to the perceived financial and security risks influencing consumers’ attitudes towards online shopping, online retailers should ensure that transactions are secure, and that customers’ personal information is protected against fraudulent activities. Retailers could use various payment systems convenient to consumers, such as PayPal or payment on delivery (for consumers who do not feel comfortable using online payment systems). Further to this, retailers should ensure that consumers receive the products they have paid for. Online retailers should give consumers the opportunity to review both the company and its products, so that potential consumers may use the information to determine the trustworthiness of the company. Consumers should also have the freedom to cancel their order and receive a refund.

Although perceived product risk was found to have no influence on attitude towards online shopping, retailers should nevertheless integrate product-related issues in retail and marketing strategies directed towards emerging-market consumers. This implies that retailers should make sure that merchandise is delivered on time, and that waiting time is communicated to consumers during the ordering period, so that they are aware of what to expect from the company. Product sizes should be clearly communicated, with accurate information to assist consumers in selecting the correct size. This is more applicable to international retailers, as sizes may differ from country to country.

6.3. Conclusion and Limitations of the Study

The purpose of this study was to answer the following research question: does attitude mediate the relationship between perceived risk and intention to shop online? To address the research question, three research objectives were formulated, as follows: to determine the perceived risk factors influencing the attitudes towards online shopping of clothing in South Africa; to ascertain if the perceived risk factors in online shopping influence consumer intention to online shopping of clothing in South Africa and to determine if consumer attitude in online shopping mediate the relationship between perceived risk and online shopping intention. All the objectives of the study have been achieved since it has been determined which perceived risk factors influence consumer attitude, and in this case, it had been determined that perceived convenience risk, perceived financial risk and perceived security risk have a significant influence on attitude towards online shopping and that perceived product risk and perceived social risk did not have significant influence on consumers’ attitude towards online shopping. It was also ascertained that none of five types of perceived risk influenced consumer intention to shop online. Regarding objective three, it was determined that consumer attitude in online shopping fully mediates the relationship between the three perceived risks – perceived finance risk, perceived convenience risk and perceived security risk and consumer online shopping intention. The two other perceived risks are not mediated by consumer attitude.

The study had some limitations, which could form the basis of future research. First, concerning the interpretation of the findings, a convenience sample comprising adult consumers restricts the generalisability of findings to other customer segments. Therefore, future research could focus on samples that are more representative of the entire consumer population. Second, this study centred on one particular product type, namely clothing; however, perceived risk factors may differ as they relate to different types of products. Future studies could therefore explore perceived risk factors in online shopping for other products. The study also involved emerging-market consumers residing in Soweto. Since risk factors might differ across different market segments, this could be investigated to determine if they indeed differ for different market segments. Future studies could also determine why perceived social risk and perceived product risk could be mediated by other factors e.g., word of mouth or website quality, since they are not mediated by consumer attitude in online shopping.

---

Author Contributions: KM Ngobeni wrote the literature section of the article and KM Makhitha designed the questionnaire, arranged for data collection, guided KM Ngobeni in the writing of the article, and completed the empirical section of the article. KM Makhitha assisted in writing some sections of the literature review, the results and the findings. KM Makhitha also arranged the statistical analyses.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article. The views expressed in the submitted article are the authors’ own, and not an official position of the institution.

---

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The views, statements, opinions, data and information presented in all publications belong exclusively to the respective Author/s and Contributor/s, and not to Sprint Investify, the journal, and/or the editorial team. Hence, the publisher and editors disclaim responsibility for any harm and/or injury to individuals or property arising from the ideas, methodologies, propositions, instructions, or products mentioned in this content.

References

- Aghekyan-Simonian, M., Forsythe, S., Kwon W.S. and Chattaraman, V., 2012. The role of product brand image and online store image on perceived risks and online purchase intentions for apparel. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 19(3), pp.325–331.

- Ajzen, I., 1991. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), pp. 179–211.

- Ariffin, S.K., Mohan, T. and Goh, Y.N., 2018. Influence of consumers’ perceived risk on consumers’ online purchase intention. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 12(3), pp. 309–327.

- Arora, N. and Aggarwal, A., 2018. The role of perceived benefits in formation of online shopping attitude among women shoppers in India. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 7(1), pp. 91–110.

- Arora, S. and Sahney, S., 2018. Consumer’s webrooming conduct: an explanation using the theory of planned behavior. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 30(4), pp. 1040–1063.

- Baron, R.M. and Kenny, D.A., 1986. The moderator‒mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, pp. 1173-1182.

- Bhatti, A., Saad, S. and Gbadebo, S.M., 2018. Convenience risk, product risk, and perceived risk influence on online shopping: moderating effect of attitude. Science Arena Publications International Journal of Business Management, 3(2), pp. 1–11.

- Bhatti, A. and Ur Rahman, S., 2019. Perceived benefits and perceived risks effect on online shopping behavior with the mediating role of consumer purchase intention in Pakistan. International Journal of Management Studies, 26(1), pp. 33-54.

- Bhattacharya, S., Sharma, R. P. and Gupta, A., 2021. Does e-retailer’s country of origin influence consumer privacy, trust and purchase intention? Journal of Consumer Marketing, pp. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-04-2021-4611.

- Bhusene, P.A. 2018. Consumers’ attitude towards online shopping in Tanzania. Doctoral dissertation, University of Dar es Salaam.

- Bizcommunity., 2019. South Africa's most lucrative and fastest-growing retail markets. [online] Available at: https://www.bizcommunity.com/Article/196/168/192803.html.

- Bizcommunity., 2018. #BizTrends2018: Township retail is taking its rightful place at the top. [online] Available at: https://www.bizcommunity.com/Article/196/730/172155.html

- Businesstech.co.za., 2022. The explosive growth of e-commerce in South Africa. [online] Available at: https://businesstech.co.za/news/business/568272/the-explosive-growth-of-e-commerce-in-south-africa/ [Accessed: 28 September 2023].

- Canguende-Valentim, C.F., 2022. Determining consumer purchase intention toward counterfeit luxury goods based on the perceived risk theory. In Handbook of Research on New Challenges and Global Outlooks in Financial Risk Management (pp. 316-339). IGI Global.

- Chaturvedi, S., Gupta, S. and Hada, D.S., 2016. Perceived risk, trust and information seeking behavior as antecedents of online apparel buying behavior in India: an exploratory study in context of Rajasthan. International Review of Management and Marketing, 6(4), pp. 935–943.

- Cherrett, T., Dickinson, J., McLeod, F., Sit, J., Bailey, G. and Whittle, G., 2017. Logistics impacts of student online shopping – evaluating delivery consolidation to halls of residence. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 78, pp. 111–128.

- Child, D., 2006. The essentials of factor analysis. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Continuum.

- Dai, H. and Chen, Y., 2015. Effects of exchange benefits, security concerns and situational privacy concerns on mobile commerce adoption. Journal of International Technology and Information Management, 24(3), pp. 41–56.

- Dai, B., Forsythe, S. and Kwon, W., 2014. The impact of online shopping experience on risk perceptions and online purchase intentions: does product category matter? Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 15(1), pp. 13–24.

- Do, T., Nguyen, T. and Nguyen, C., 2019. Online Shopping in an Emerging Market: The Critical Factors Affecting Customer Purchase Intention in Vietnam. Journal of Economics and Management Sciences, 2(2), pp. 1-11.

- Engineeringnews.co.za, 2021. Online retail booms, set to stabilise at higher level. [online] Available at: https://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/online-retail-booms-set-to-stabilise-at-higher-level-2021-05-12/rep_id:4136.

- Euromonitor., 2017. Growth of retail in South Africa. [online] Available at: https://blog.euromonitor.com/2017/10/growth-internet-retail-south-africa.html

- Farhana, N., Khan, T. and Noor, S., 2017. Factors affecting the attitude towards online shopping: An empirical study on urban youth in Bangladesh. Aust. Acad. Bus. Econ. Rev, 3(4), pp. 224–234.

- Featherman, M.S. and Wells, J.D., 2010. The intangibility of e-services: effects on perceived risk and acceptance. ACM SIGMIS Database: The Database for Advances in Information Systems, 41(2), pp.110–131.

- Field, A. and Miles, J., 2010. Discovering statistics using SAS. Richmond: Sage Publications.

- Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I., 1975. Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: an introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

- GFK., 2017. Connecting with the township consumer: Aligning your brand and marketing with the needs and motivations of township consumers to add value to their lives. [online] Available at: https://www.gfk.com/insights/connecting-with-the-township consumerpdfs/fileadmin/user_upload/country_one_pager/za/documents/gfk_township_marketing_report.pdf.

- Goga, S.I., Paelo, A. and Nyamwena, J., 2019. Online retailing in South Africa: an overview. 1–39.

- Ha, N.T., 2020. The impact of perceived risk on consumers’ online shopping intention: An integration of TAM and TPB. Management Science Letters, 10, pp. 2029–2036.

- Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E. and Tatham, R.L., 2006. Multivariant data analysis. New Jersey: Pearson International.

- Han, M.C. and Kim, Y., 2017. Why consumers hesitate to shop online: perceived risk and product involvement on Taobao.com. Journal of Promotion Management, 23(1), pp. 24–44.

- Hasan, M.K., Ray, R. and Neela, N.M., 2021. Tourists’ behavioural intention in coastal tourism settings: Examining the mediating role of attitude to behaviour. Tourism Planning & Development, pp.1-18.

- Hilken, T., Heller, J., Chylinski, M., Keeling, D.I., Mahr, D. and de Ruyter, K., 2018. Making Omnichannel an augmented reality: the current and future state of the art. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 12(4), pp. 509–523.

- Hong, I.B., 2015. Understanding the consumer's online merchant selection process: the roles of product involvement, perceived risk, and trust expectation. International Journal of Information Management, 35(3), pp. 322–336.

- Hong, L.M., Zulkiffli, W.F. and Hamsani, N.H., 2019. The impact of perceived risks towards customer attitude in online shopping. International Journal of Accounting, Finance and Business, 1(2), pp. 13–21.

- Hong, Z. and Yi, L., 2012. Research on the influence of perceived risk in consumer online purchasing decision. Physics Procedia, 24(B), pp. 1304–1310.

- Hsieh, M. and Tsao, W., 2014. Reducing perceived online shopping risk to enhance loyalty: website quality perspective. Journal of Risk Research, 17(2), pp. 241–261.

- Hsu, S.H. and Luan, P.M., 2017. The perception risk of online shopping impacted on the consumer’s attitude and purchase intention in Hanoi, Vietnam. Journal of Business & Economic Policy, 4(4), pp. 19–29.

- Hu, L.T. and Bentler, P.M., 1999. Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modelling, 6(1), pp. 1–55.

- Ilmudeen, A., 2014. Consumers' perceived security risks in online shopping: A survey study in Sri Lanka. Proceedings of International Conference on Contemporary Management, pp. 857–866.

- Jaiswal, D., Kaushal, V., Kant, R. and Singh, P.K., 2021. Consumer adoption intention for electric vehicles: Insights and evidence from Indian sustainable transportation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, pp. 1–13.

- Javadi, M.H.M., Dolatabadi, H.R., Nourbakhsh, M., Poursaeedi, A. and Asadollahi, A.R., 2012. An analysis of factors affecting online shopping behavior of consumers. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 4(5), pp. 81–98.

- Jiang, X., Qin, J., Gao, J. and Gossage, M.G., 2022. The mediation of perceived risk’s impact on destination image and travel intention: An empirical study of Chengdu, China during COVID-19. PLOS one, 17(1), pp. 1-23.

- Jun, G. and Jaafar, N.I., 2011. A study on consumers’ attitude towards online shopping in China. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(22), pp. 122–132.

- Kaplan, D., 2001. Structural equation modeling. In N. J. Smelser and P. B. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences, 11, pp. 15215-15222. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Katta, R.M.R and Patro, C.S., 2017. Influence of Perceived Risks on Consumers' Online Purchase Behaviour: A Study. International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development (IJSKD), 9(3), pp. 17–37. https://10.4018/IJSKD.2017070102.

- Keisidou, E., Sarigiannidis, L. and Maditinos, D., 2011. Consumer characteristics and their effect on accepting online shopping, in the context of different product types. International Journal of Business Science & Applied Management (IJBSAM), 6(2), pp. 31–51.

- Khan, N.J., Razzaque, M.A. and Hazrul, N.M., 2017. Intention of, and commitment towards, purchasing luxury products. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 8(3), pp. 476–495.

- Kaur, A., and Thakur, P., 2021. Determinants of Tier 2 Indian consumer’s online shopping attitude: a SEM approach. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 33(6), pp.1309–1338. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-11-2018-0494.

- Koay, K.Y., 2018. Understanding consumers’ purchase intention towards counterfeit luxury goods: An integrated model of neutralisation techniques and perceived risk theory. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 30(2), pp. 495-516.

- Lavuri, R., Jindal, A. and Akram, U., 2022. How perceived utilitarian and hedonic value influence online impulse shopping in India? Moderating role of perceived trust and perceived risk. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 14(4), pp. 615–634.https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-11-2021-0169.

- Liebenberg, J., Benade, T. and Ellis, S., 2018. Acceptance of ICT: Applicability of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) to South African Students. The African Journal of Information Systems, 10(3), pp. 160-173.

- Makhitha, K.M. and Ngobeni, K., 2021a. The influence of demographic factors on perceived risks affecting attitude towards online shopping. South African Journal of Information Management, 23(1), a1283. https://doi.org/10.4102/ sajim.v23i1.1283.

- Makhitha, K.M. and Ngobeni, K.M., 2021b. The impact of risk factors on South African consumers’ attitude towards online shopping. Acta Commercii, 21(1), pp. 1–10.

- Malapane, T.A., 2019, April. A risk analysis of e-commerce: a case of South African online shopping space. In 2019 Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium (SIEDS), pp. 1–6.

- Malhotra, N.K., 2010. Marketing research: an applied orientation. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice-Hall.

- Mapande, F.V. and Appiah, M., 2018. The factors influencing customers to conduct online shopping: South African perspective. International Conference on Intelligent and Innovative Computing Applications (ICONIC), Mon Trésor, Mauritius, December 6–7, pp. 1–5.

- Marza, S., Idris, I. and Abror, A., 2019. The influence of convenience, enjoyment, perceived risk, and trust on the attitude toward online shopping. Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, 64, pp. 588–597.

- Maziriri, E.T and Chuchu, T., 2017. The Conception of Consumer Perceived Risk towards Online Purchases of Apparel and an Idiosyncratic Scrutiny of Perceived Social Risk: A Review of Literature. International Review of Management and Marketing, 7(3), pp. 257-265.

- Moeti, M.N., Mokwena, S.N. and Malebana, D.D., 2021. The acceptance and use of online shopping in Limpopo province. SA Journal of Information Management, 23(1), pp. 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajim.v23i1.1313.

- Mofokeng, T. E., 2021. The impact of online shopping attributes on customer satisfaction and loyalty: Moderating effects of e-commerce experience. Cogent Business & Management , 8(1), pp. 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1968206

- Mosunmola, A., Omotayo, A. and Mayowa, A., 2018. Assessing the influence of consumer perceived value, trust and attitude on purchase intention of online shopping. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on E-Education, E-Business, E-Management and E-Learning, pp. 40–47.

- Masoud, E.Y., 2013. The effect of perceived risk on online shopping in Jordan. European Journal of Business and Management, 5(6), pp.76-87.

- Muda, M., Mohd, R. and Hassan, S., 2016. Online purchase behavior of generation Y in Malaysia. Procedia Economics and Finance, 37(16), pp. 292–298.

- Mutahar, A. M., Alam, S., Daud, N. M., Alam, S., Thurasamy, R., Isaac, O. and Alam, S., 2018. The mediating of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use: The case of mobile banking in Yemen. (2021). International Journal of Technology Diffusion, 9(2), pp. 21–22. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJTD.2018040102.