Keywordsentertainment LGBTQ promotion queer social identity theory

JEL Classification M31

Full Article

1. Introduction

In 2018, a gay romance TV series became popular throughout Japan. The show, Ossan’s Love [Middle-Age Men in Love], was broadcast on one of Japan’s six major TV stations and became popular with both homosexual and heterosexual audiences (News Post Seven, 2018). The show’s official Instagram account amassed more than 400,000 followers, and the official fake account, which was created to be the account of the show’s character called Musashi, amassed almost 500,000 followers. The hashtag ‘ossanslove (in Japanese)’ became the top Twitter trend handle worldwide when the show was first broadcast on TV in 2018. The show gained popularity through word of mouth, a phenomenon that was extraordinary because generally, entertainment content with sexual minority themes generally does not draw wide audiences (Cavalcante, 2013). Thus, publicists tend to avoid emphasising sexual minority themes explicitly in promotional materials (Cavalcante, 2013). In Japan, publicists traditionally replace ‘homosexual romance’ with ‘human romance’ and rarely mention sexual minority themes in synopses when promoting gay-themed films (Real Sound, 2018). However, Ossan’s Love was advertised as a love story about men openly from the beginning in its poster art. From the perspective of social identity theory, it is difficult to explain why this show attracted both homosexual and heterosexual viewers.

Extant studies have found that media content with controversial themes, including gay themes, often have used paratextual promotional strategies (Brookey and Westerfelhaus, 2002; Cooper and Pease, 2008; King, 2010; Lotz, 2004). Paratexts concern ‘the thresholds of interpretation’ (Genette, 1997). According to Genette (1997), paratexts influence people when they decide whether, for example, to read a book and also control readers’ interpretations while reading the text of published literature. However, published literature comprises more than the main text and includes cover art with a title, the author’s name, and the publisher’s name on it. Also, it may have a preface, introduction, illustrations, author’s notes etc. All these materials can be viewed as paratexts and can neutralise and domesticate potentially negative points, such as minority themes, in a story (Cavalcante, 2013; Martin and Battles, 2021). Paratexts in other entertainment media, including TV shows and movies, include audience reviews, promotional tools and interviews with producers. Paratexts create various expectations and guide viewers as they enter a show’s world (Gray, 2008). Thus, this research analysed relevant paratexts of Ossan’s Love – such as promotional posters, media articles and audience reviews – to determine why a wide audience was attracted to the show’s gay themes. This analysis determined that important paratexts were in play that enabled both heterosexual and homosexual audiences to embrace this minority-themed entertainment.

This study provides practical implications for creators and marketers of entertainment products such as TV dramas and movies. It also theoretically contributes to the thesis that consumers will overlook the line between different social groups when they perceive positive emotions in promotional materials.

2. Literature Review

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and/or questioning (LGBTQ) issues have been a growing topic in entertainment media worldwide, including films, TV programmes and music videos (Bond, 2014). Numerous researchers have conducted case studies on specific films or TV shows with LGBTQ themes or LGBTQ recognition, such as TransAmerica, Xena: Warrior Princess, Queer as Folk, Sherlock, Happiest Season, and Love, Simon (Cavalcante, 2013; Francis, 2021; Greer, 2014; Manuel, 2009; Maris, 2016). Some studies focussed on the non-LGBTQ audience’s perception of LGBTQ shows in society (Manuel, 2009; Sabharwal and Sen, 2012). For example, Manuel (2009) examined Queer as Folk, a US gay-themed TV series broadcasted from 2000 to 2005 that both heterosexual and homosexual audiences embraced. Through a semiotic reading, Manuel (2009) found that an overtly sexualised homosexual makes heterosexual viewers become ‘homovoyeurs’, a new type of audience that enjoys observing the gay world. Characters with sex appeal attract heterosexual viewers, mostly female viewers, despite the gay-themed story. Thus, the show must be ‘sexy’ to capture viewers’ attention (Shiller, 2003).

Similarly, Boys’ love (BL), a genre of Japanese manga comics that explicitly deals with homoerotic male interaction, is very popular, particularly among young women, not only in Japan, but also in other countries (Martin, 2012). Martin (2012) conducted interviews with female BL readers and found that they enjoy romantic, pornographic scenes between young men as fantasy romance. Considering that female readers cannot have a romantic relationship with another man as a gay male, BL is not realistic, but rather a dream world for them. Simultaneously, BL is a great opportunity for readers to consider their own gender, sexuality and generation (Martin, 2012). It has been posited that readers use BL to escape from social norms in their society (Suter, 2013).

However, Manuel (2009) stated that straight people can enjoy homosexual stories because the medium – whether TV, movies or books – functions as a bridge between themselves and the gay world. This bridge plays an important role in offering meaningful interaction across the heterosexual and homosexual identity boundary (Manuel, 2009).

Although many consumers have preferences concerning gay-themed content, entertainment professionals ordinarily tend to hide LGBTQ aspects of their films or TV shows when they promote them to a mainstream audience (Cavalcante, 2013). From the perspective of social identity theory, it is natural for heterosexual consumers to prefer heterosexual imagery over homosexual imagery, while homosexual consumers have responded negatively to heterosexual imagery in advertising (Eisend and Hermann, 2019; Gong, 2019; Sánchez-Soriano and García-Jiménez, 2020). Accordingly, it would seem to be very difficult to send positive promotional messages to both heterosexual and homosexual audiences with the same promotional materials. Cavalcante (2013) examined paratexts from the 2015 US comedy-drama film TransAmerica, whose main character was a transgender woman. Through analysis of paratexts such as audience reviews, movie posters and director commentary on DVDs, Cavalcante (2013) found that people who saw the film were upset about its marketing strategy because the film’s transgender themes were totally hidden, and the marketing team seemed to try and make the potential audience think the film was a simple family drama. However, their ‘marketing ploy’ actually caused wider discussion about sexuality issues (Cavalcante, 2013). It can be stated that TransAmerica’s marketing strategy was successful, as the film gathered attention from a wider audience as a family drama before its release and provided an opportunity to reflect on discrimination against transgender people after its release. It is uncertain whether the film would have attracted both heterosexual and homosexual audiences had the marketers revealed its transgender themes in the promotional materials. However, when considering the marketing approach from the transgender perspective, trans people would not have been able to discern that the film’s main character was a transsexual woman based on the film’s marketing materials. While it was suggested that entertainment media can be important sexual socialisation agents for LGBTQ people (Bond, 2014), there may be better ways to promote media products than hiding their LGBTQ elements.

As noted earlier, the marketing strategy for Ossan’s Love took a direct approach and attracted both gay and heterosexual viewers with the same promotional tools, i.e., paratexts from Ossan’s Love created various expectations that guided viewers as they entered the show’s world, as Gray (2008) suggested. Prior researchers have indicated that paratexts cover up or domesticate the potential meanings of controversial themes in entertainment or other media content (Lotz, 2004; Mendelsohn, 2006). Paratexts such as promotional posters and interviews with producers shape marketing messages from the creators’ perspective, which can mislead consumers who have no idea what a show or movie is about. If consumers feel that the marketers and promoters misled them after watching a show, the reviews are more likely to be negative, similar to the ones for TransAmerica, which Cavalcante (2013) studied. However, in the case of Ossan’s Love, this kind of ‘marketing ploy’ did not exist.

Thus, today’s research question is: What kind of paratextual messages from Ossan’s Love positively influenced both heterosexual and homosexual audiences?

3. Method

This research engaged in a textual analysis based on Cavalcante (2013), who analysed paratexts from the US film TransAmerica. Cavalcante (2013) chose two promotional posters, the cover art for its DVD and the director commentary on the DVD extra for analysis. Other than these, it is suggested that film reviews and other promotional tools can be effective product paratexts (Cavalcante, 2013). Among various paratexts of Ossan’s Love, this research chose promotional posters, articles that included interviews with the producer, and online reviews from both heterosexual and homosexual viewers. There are some reasons why paratextual materials were chosen for this study. Promotional posters and interviews with the producer should be reasonable choices for analysis considering that Cavalcante (2013) also chose such materials. The online audience reviews will be helpful in revealing how people view the show’s homosexuality. Considering that some reviewers disclosed their homosexual orientation in their reviews, it is possible to compare heterosexual and homosexual viewers’ thoughts and feelings about this gay-themed show. This research uses reviews from Yahoo! Japan TV (tv.yahoo.co.jp/review/356787/), one of the most popular TV review sites in Japan. Also, blog articles were collected through online searches using keywords such as Ossan’s Love, review and blog. Altogether, 361 reviews were selected for analysis.

4. Results

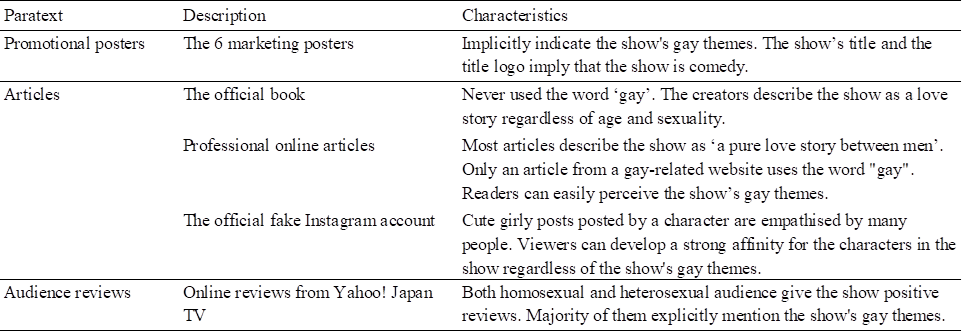

The research results are described after the summary of the analysis shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. The summary of the analysis

4.1. Promotional Posters

The six marketing posters (#1 to #6) were used to promote the show. They were displayed together in public places.

The lead character is in Poster #1. One man, who has an anxious look on his face, is putting his hand on another man’s shoulder as the two are hugging. The advertising copy of the poster says, ‘One day, my boss confessed his love for me’. Consumers clearly recognised that this man is expressed homosexual affection from his boss. The actor is Kei Tanaka, who started his acting career in 2003 and landed his first lead TV role in 2008. Thus, he was an experienced and famous actor before Ossan’s Love, so many people probably recognised him when they saw this poster. However, considering that he has played myriad types of characters in various film and TV genres, he has no fixed image as an actor. Thus, few people would have had preconceptions about this show just because Tanaka was the star. Moreover, he never had played an explicitly gay character before this role.

The boss, who is referred to in the copy of Poster #1, is shown in Poster #2, in which a middle-age man with a moustache, eyes closed, is shown clinging tenderly to another man’s chest. The advertising copy says, ‘I happened to fall in love with a man. That’s all there is to it’. This poster may make people feel strange because the man’s facial expression can be viewed as that of a young girl in love. Another experienced actor, Kotaro Yoshida, played the boss. He is a famous supporting actor from films, other TV shows and theatrical productions. Considering that Yoshida sometimes plays funny characters in comedy films and TV dramas, some consumers may have assumed that Ossan’s Love is a comedy after seeing this poster.

Another male character in Poster #3 looks straight at the camera with strong eyes, and the copy says, ‘I confessed my love for my colleague. And said, “just kidding” at the end’. People may not be able to recognise that the colleague clearly is a male, but the poster implies it by showing the chest of another man wearing a suit behind the character in the foreground. Young actor Kento Hayashi plays this character. He has played gay characters twice before Ossan’s Love – in the 2010 Japanese film Akuno Kyoten [Lesson of the Evil] and in the 2016 Japanese film Nigakute Amai [Bitter Sweet]. However, his character in Akuno Kyoten was not the lead role, and Nigakute Amai was an independent film with a limited release although his character was the lead role. Hayashi is more famous for the main roles in other many films and dramas such as Arakawa under the bridge (2011) and Hibana [Spark] (2016). Thus, not so many viewers would have view him as an actor who often plays homosexual characters, and it is unlikely that many viewers would have assumed that Ossan’s Love was a gay drama merely because he was in it. The poster delivered the message that it was a gay drama. Compared with the rest of the cast, Hayashi is young, and some viewers may have had high expectations that he would have a romantic relationship with another older male character. BL fans in particular likely were happy to see the young and handsome Hayashi playing a gay role.

In Poster #4, another man is shown, with the quote, ‘If I had known it would be so painful, I wouldn’t have fallen in love’. The statement didn’t clearly indicate that this character’s lover was a guy, but it implicitly indicates his homosexuality by showing all other posters at once. Also, another male in a suit could be seen in the background of this poster as well. Thus, some consumers may have become interested in this drama because they imagined that this character's tormented love interest in this marketing copy was actually a man. However, Hidekazu Mashima, who played the character in Poster #4, did not have a gay image based on previous roles.

Two other posters featured female characters saying, ‘I totally thought it was another woman when he wanted a divorce’ (Poster #5) and ‘Women’s love rivals are always other women. Such a stereotype is no longer true now’ (Poster #6). This suggested that these female characters were heterosexual and seemed that they are not homophobic. Viewers easily could guess that these women were in relationships with male characters on the show.

These posters’ images and text might have made consumers think the show was a serious homosexual love story, but considering that the word Ossan is an impolite form of middle-age-man and would be inappropriate for social issue drama, most Japanese consumers viewed the show as a comedy. Along with the show’s title, the title logo implied that the show was not a serious drama. Thus, many audience members may have thought there would be gay romances they could laugh at on the show. However, others may have felt sexual attraction after seeing the posters. According to Tabata (2018), many online comments focussed on the actors’ appearance in these posters, e.g., ‘The marketing copy and the actors’ looks are perfect!’, ‘The boss is cute’, and ‘Kei Tanaka is really sexy’. Shiller (2003) suggested that gay-themed shows must be sexy to attract an audience, even if the bulk of the audience is heterosexual. Although the Ossan’s Love posters were not explicitly erotic, the expectation of good-looking actors in love with another handsome guy may be sexy enough for consumers.

The L Word, a US TV series about the lesbian community in LA, included real-life lesbians and bisexuals in its staff and cast, but no actors or creative personnel behind the camera on this show officially had disclosed their sexual orientation publicly. Some, including Tanaka, have opposite-sex spouses in their private lives. This may be a negative point for homosexual viewers, but considering that very few TV show creators and actors in Japan are openly homosexual to begin with, many LGBTQ people likely did not expect to see people from their community participating in the show. Some of them may have assumed that this was another homosexual show made by heterosexuals, but this show was known for having strong support from the gay community, which is discussed later.

4.2. Articles

In the official book of the show Ossan’s Love (TV Asahi, 2018), the producer and writer talk about the process of making the series. They never used the word ‘gay’, nor did theyrefer to gay themes in the show, similar to the director’s audio commentary on the TransAmerica DVD (Cavalcante, 2013). Both the producer and writer of Ossan’s Love like girls’ manga (manga comics for young girls that focus mostly on teen love and relationships) and romance TV series. They stated that they just wanted to make a classic love story that resembled their favourite manga and TV series. They actually didn’t view the show as a comedy, but knew that the audience would focus on the homosexual relationships between ‘Ossan’ (middle-age men) rather than the story when they first watched the show. Even so, they tried to show the audience ‘what love is’ through the story regardless of age and sexuality.

However, most online articles described the show as ‘a pure love story between men’, and they rarely used the word ‘gay’, particularly in headlines. Only one LGBTQ-related website described the show as ‘A love triangle story among gay and straight’ in a headline (Rainbow Life, 2018). However, readers easily could have perceived the show’s gay themes, unlike the TransAmerica case that Cavalcante (2013) studied. By not using the word ‘gay’ or ‘queer’, Ossan’s Love viewers may have assumed that the show’s creators believe heterosexuality and homosexuality do not need to be distinguished.

Many articles discussed the official fake Instagram account for Ossan’s Love, which was supposed to be owned by the boss character, Musashi Kurosawa (played by Kotraro Yoshida). The name of the Instagram account was Musashi-no-heya (Musashi’s room). On the show, Musashi falls in love with the lead character, Soichi Haruta (played by Kei Tanaka), and consumers could see unpublished photos of Soichi taken secretly by Musashi on the Instagram page. This account quickly captured viewers’ attention and amassed 126,000 followers within a month after Ossan’s Love debuted in April 2018 (ORICON NEWS, 2018). The phenomenon was so extraordinary that the show’s social media marketing was highly regarded in online articles with headlines such as ‘Viewers are addicted to the official fake Instagram account “Musashi’s room”’, ‘The official Instagram account “Musashi’s room” rapidly gained over 120,000 followers’ and ‘Ossan’s Love: The official Instagram account which has a lot of cute girly posts by Kotaro Yoshida started secretly. He takes sneak shots of Kei Tanaka’.

Musashi acted like a shy and naive teen girl, a character typically seen in girl’s manga. Several articles kiddingly called him a ‘female lead’. Some people just laughed at these posts, while others empathised with Musashi, who was depicted as a pure person in one-way love. The former group may have thought that the drama was a comedy, but the latter group might have viewed the drama as a heart-rending love story. In the official book, the producer stated, ‘Instagram followers are very sympathetic to the boss (Musashi). I am impressed that they posted lots of comments on Instagram to comfort the boss when he is heartbroken in the show’ (TV Asahi, 2018, p. 83). It is possible that the Instagram posts were effective at causing viewers to develop a strong affinity for the characters, viewing them like real-life friends. However, viewers may not have cared whether the show had homosexual themes, as they might have just wanted to see their favourite characters and stories. The boss character may not have really existed, but he has succeeded at grabbing viewers’ attention as a relatable character.

4.3. Audience Reviews

Viewers evaluated this show highly as a ‘hetero-produced gay drama that obtained few complaints from gay people’ (News Post Seven, 2018). One gay blogger wrote, ‘There are no characters who are negative towards homosexuals in this show. Moreover, the creators express our subtle feelings without using the word “gay”’. Another gay audience member wrote, ‘I thought this show might be one of the typical Japanese gay comedies that make fun of a gay who confesses his love for a straight man. But I was wrong. Nobody denies homosexuals in this show’. A bisexual female fan of the show wrote, ‘Nobody dies or gets a serious disease on this show like other typical gay-themed dramas and films. Guys who fall in love with other guys, and guys who are loved by other guys are living very normally with heterosexual people on this show. Yes, I’ve wanted to see such a drama!! I can really empathise with the characters’. A bisexual male audience member also empathised with the characters and posted an article on his blog, stating, ‘The struggle of the boss who has a feeling for Kei Tanaka and the feelings of Kento Hayashi, who involuntarily treats Kei Tanaka badly, are painfully depicted in this show. I know it is very hard when LGBTQ people fall in love with straight people because I’m bisexual (crying)’. It has been posited that LGBTQ audience members were tired of tragic or hetero-normative sexual minority stories. Existing research indicates that sexual minorities connect with gay- and lesbian-oriented media based on their own experiences as LGBTQ individuals (e.g. Bond, 2015; Winderman and Smith, 2016). Winderman and Smith (2016) also suggested that sexual minority viewers might watch LGBTQ-inclusive TV to see their sexual identities portrayed positively. Thus, it was natural that Ossan’s Love, in which the gay characters existed in a normal manner in the show’s world, would attract sexual minority viewers. The viewer reviews included many homosexuals who wanted to thank the creators of the show for showing an ideal world for them. However, the potential audience from the LGBTQ community may have had positive expectations for this show in the first place, reflected in these favourable reviews.

However, the bulk of the heterosexual audience also gave the show positive reviews. A heterosexual audience member said, ‘I don’t feel upset because this show has gay relationships. Rather, I feel empathy for them and can’t help rooting for them’. Other heterosexual audience members stated, ‘Usually, I’m not interested in homosexual shows. If anything, I don’t like them, but I laughed a lot watching this show. I will keep watching their triangular relationships through the end of the season’, ‘There are no reasons to love someone. I felt that it was OK to just love, regardless of all the barriers and laws. I actually didn’t like romantic drama, but I’m hooked on this show’ and ‘I’m a middle-age woman and watched the first episode. It was so fun and totally blew my mind! It not only made me laugh, but also made me think about the meaning of “falling in love with someone”’. In reviews by heterosexual audience members, it was found that most reviewers stated that the show could be amusing and recommended the show as a quality comedy, rather than a gay drama. Also, many reviewers wrote that they liked this show as a pure love story, while others recognised that the show dealt with delicate themes. However, many reviewers did not care that romance emerged between men, as they seemed to be touched by the characters’ way of loving, and sexuality did not matter to them. Thus, the show generated empathy even among the heterosexual audience. One review stated, ‘They are full of compassion and unconditional love for loved ones in this show. No one dies, no one gets injured or sick, and no one is a jerk. It’s a rare drama full of laugh-out-loud moments’.

Most reviewers positively reviewed the show, with the average review score from 427 viewers at 4.81 stars out of five on Yahoo! Japan TV. These positive reviews may have drawn attention from potential viewers who wanted to see a good show regardless of their gender and sexuality.

However, few reviews suggested watching this drama to discuss LGBTQ issues. Manuel (2009) stated that gay-themed shows need to ask what homosexual representation can do for the gay and lesbian civil rights agenda as an influential medium. In this sense, the contribution of Ossan's Love to the LGBTQ community appears to be low. However, in the show’s universe, the gay characters appear to have secured their civil rights because other characters never discriminate against them. This could be viewed as a way to show viewers an ideal world that they should aim for in the future. The audience appeared to have accepted this setting.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

According to Cavalcante (2013), paratexts performed a complex ‘double work’ in the case of TransAmerica. The film’s marketers hid the film’s sexual minority themes to attract a wider audience when they promoted the film, which elicited discussions about transgender issues without marketers’ intentions. Paratexts can be used to deceive people, and paratextuality usually has been theorised as an ability to distance media products from specific themes, including LGBTQ issues (Cavalcante, 2013). However, consumers already have realised that paratext is not completely reliable because every consumer probably has been misled or deceived by paratexts once or twice in the past. Therefore, when major themes, such as LGBTQ themes, are hidden, some consumers from a particular audience segment cannot afford to overlook them. Moreover, considering that this hetero-normative society often excludes the LGBTQ community, viewing it as a threat to the status quo, consumers who are sensitive to human rights issues, including sexual minority consumers themselves, should be able to discuss them. This may be how ‘double work’ occurs. In the case of Ossan’s Love, the creators and marketers didn’t use the word ‘gay’, like in the case of TransAmerica, whose transgender themes were hidden in the promotional materials. This means that paratexts from Ossan’s Love could perform ‘double work’, and there was a distinct possibility that consumers could have criticised the show for hiding the controversial themes on purpose. However, it seems that ‘double work’ was not perceived in the case of Ossan’s Love. Although the word ‘gay’ was not used in the show’s promotional materials, people easily could discover that the show included homosexual relationships through paratexts such as posters, marketing materials and interviews with the show’s creative team. Simultaneously, it is likely that consumers understood the creators’ intention for this show, which was to depict pure love relationships regardless of gender. Consumers who watched the drama may have realised that marketers did not use the word ‘gay’ because, paradoxically, the marketers did not perceive it as something that had to be hidden to attract heterosexual viewers. Based on online reviews, most viewers, regardless of their sexuality, appreciated that this drama was a romantic comedy. It is also noteworthy that none of the show’s characters discriminated against gay people, and some consumers may have noticed this when they read the marketing copy in the promotional posters. This also may be one of the reasons why there were few critical discussions about any ‘marketing ploy’ in reviews or blog articles. Viewers positively accepted the promotional methods and agreed with the creators’ ideas. Some homosexual viewers thanked the creators in their reviews for portraying the gay characters as people with whom viewers can empathise. Even heterosexual viewers wrote that they could empathise with the gay characters beyond sexual orientation. Furthermore, such viewers’ voices may influence potential viewers through the paratext of word of mouth. In that sense, it can be asserted that paratexts of Ossan’s Love performed ‘amplifying work’ instead of ‘double work’.

However, extant research found that heterosexual females have more tolerance for homosexuality than heterosexual males do (Akermanidis and Venter, 2014). Thus, it would seem more difficult to gain attention from heterosexual males when publicists promote gay-themed shows. If this show had been a serious gay drama, many heterosexual male audience members might not have agreed to watch it. Considering that the paratexts indicated the show was a comedy, heterosexual males might have felt more comfortable watching this show, as some strongly refused to watch dramas that include gay scenes. In this case, they could avoid watching the show after realising the show contains homosexual relationships based on the show’s paratexts. One female audience member’s review stated, ‘I love reading other positive reviews here since there is no other viewers around me, including my husband. My husband refuses to watch this show in the first place’. If the homosexual themes were completely hidden in paratexts of Ossan’s Love, such male audience members may have criticised the show’s marketing strategy, and ‘double work’ might have occurred in the paratexts.

Among homosexual audiences, some at first seemed to think that the show was a stereotypical comedy that laughed at gay people. However, they basically were interested in gay-themed entertainment and had few reasons to be reluctant to watch this show. As Bond (2014) suggested, LGBTQ-themed media can be important resources when living as a sexual minority in this society for homosexuals. Moreover, the fact that this show did not have any evil characters who bullied or despised gay people elicited positive reactions from both heterosexual and homosexual audiences. Simultaneously, it is possible to criticise the show for turning away from the reality that gay people have difficulties living in our society; however, many audience members thought that the show offered an ‘ideal society’ in which everyone accepts diversity and different sexualities. The show’s promotional materials, including posters and books, may have been designed under such a concept. It also can be assumed that the show’s creators set up this show’s universe based on such a concept in the first place. Therefore, it can be concluded that heterosexual audiences accepted the show’s homosexual themes consciously or unconsciously after positively reacting to the promotional materials. Although gay-themed content should be consumed mainly by homosexual consumers from the perspective of social identity theory, it has been suggested that homosexuals and heterosexuals can be united under the same social identity beyond sexual identity when they share the idea of an ideal society.

5.1. Limitations and Future Research

This research aimed to determine what kinds of paratextual messages in gay-themed content attract both homosexual and heterosexual consumers. Considering the case of Ossan’s Love, it has been suggested that if the paratext conveys a peaceful and ideal universe for the show, then viewers will perceive the gay drama positively regardless of their sexual orientation. However, if gay-themed dramas need to play a role in provoking social discussion, a paratext in which ‘double work’ does not occur may be an obstacle to creating an ideal society. It can be said that the paratexts of TransAmerica succeeded in promoting social understanding of transgender people by generating discussions. Although the paratexts of Ossan’s Love brought heterosexuals and homosexuals together by sharing an ideal society, it is unclear whether this drama promoted society’s understanding of LGBTQ communities. Japan is a country in which understanding of the LGBTQ community is far from advanced. In a report published in 2019 by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) on the status of LGBTQ laws and regulations in its member countries, Japan ranked 34th out of 35 OECD countries, the second worst after Turkey (OECD, 2019). Considering the current situation in Japan, influential media content, such as TV shows, may be required to send out powerful messages to change societal perceptions. If the paratexts had been analysed from a social perspective, this study’s results might have been different.

However, this show actually had a sequel series, called Ossan’s Love in the Sky, which aired in November and December 2019. The lead and boss characters’ story continued, but other characters and settings were completely redesigned. Although the show’s creative team, including the producer and writer, remained, this second series was not as enthusiastically supported as the first. The difference in popularity between the first and second seasons was obvious because many people wrote reviews on Yahoo! Japan TV stating that they were disappointed. This might have been tied to production reasons, major changes in settings or the loss of popular characters from the first season. However, paratexts also may have influenced this. An interesting future study could compare both seasons.

Paratext may affect promotional content while simultaneously bringing society together and eliciting discussion. Nevertheless, as Cavalcante (2013) noted, academic research on paratext remains lacking. Future studies should examine paratexts in various fields.

---

Funding:This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest: The author states that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akermanidis, E. and Venter, M., 2014. Erasing the line between homosexual and heterosexual advertising: A perspective from the educated youth population. The Retail and Marketing Review, 10, pp. 50–64.

- Bond, B. J., 2014. Sex and Sexuality in Entertainment Media Popular With Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adolescents. Mass Communication and Society, 17, pp. 98–120.

- Bond, B. J., 2015. The mediating role of self-discrepancies in the relationship between media exposure and well-being among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents. Media Psychology, 18, pp. 51–73.

- Brookey, R.A. and Westerfelhaus, R., 2002. Hiding homoeroticism in plain view: The Fight Club DVD as digital closet. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 19(1), pp. 21–43.

- Cavalcante, A., 2013. Centering Transgender Identity via the Textual Periphery: TransAmerica and the “Double Work” of Paratexts. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 30(2), pp. 85–101.

- Cooper, B. and Pease, E., 2008. Framing Brokeback mountain: How the popular press corralled the “gay cowboy movie”. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 25(3), pp. 249–273.

- Eisend, M. and Hermann, E., 2019. Consumer Responses to Homosexual Imagery in Advertising: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Advertising, 48(4), pp. 380–400.

- Francis, I., 2021. Homonormativity and the queer love story in Love, Simon (2018) and Happiest Season (2020). Women’s Studies Journal, 35(1), pp. 80–93.

- Genette, G., 1997. Paratexts: Thresholds of interpretation. Translated by J. E. Lewin. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Gong, Z. H., 2019. Crafting Mixed Sexual Advertisements for Mainstream Media: Examining the Impact of Homosexual and Heterosexual Imagery Inclusion on Advertising Effectiveness. Journal of Homosexuality, 67(7), pp. 916–939.

- Gray, J., 2008. Television pre-views and the meaning of hype. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 11(1), pp. 33–49.

- Greer, S., 2014. Queer (Mis)recognition in the BBC’s Sherlock. Adaptation, 8(1), pp. 50–67.

- King, C.S., 2010. Un-queering horror: Hellbent and the policing of the “gay slasher”. Western Journal of Communication, 74(3), pp. 249–268.

- Lotz, A., 2004. Textual (im)possibilities in the US post-network era: Negotiating production and promotion processes on Lifetime’s Any day now. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 21(1), pp. 22–43.

- Manuel, S. L., 2009. Becoming the homovoyeur: consuming homosexual representation in Queer as Folk. Social Semiotics, 19(3), pp. 275–291.

- Maris, E., 2016. Hacking Xena: Technological innovation and queer influence in the production of mainstream television. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 33(1), pp. 123–137.

- Martin, F., 2012. Girls who love boys’ love: Japanese homoerotic manga as trans-national Taiwan culture. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 13(3), pp. 365–383.

- Martin Jr., A.L. and Battles, K., 2021. The straight labor of playing gay, Critical Studies in Media Communication, 38(2), pp. 127–140.

- Mendelsohn, D., 2006. An affair to remember. The New York Review of Books. [online] Available at: http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2006/feb/23/an-affair-to-remember/ [Accessed on 3 December 2021].

- News Post Seven., 2018. ‘Ossan’s Love’: LGBT kanren no kujo ga hobonai noha nazeka [translation: ‘Ossan’s Love’: Why the show has few claims regarding LGBT.] [online] Available at: https://www.news-postseven.com/archives/20180519_677192.html/2 [Accessed on 3 December 2021].

- OECD, 2019. Society at a Glance 2019: OECD Social Indicators, OECD Publishing. [online] Available at: https://doi.org/10.1787/soc_glance-2019-en [Accessed on 3 December 2021].

- ORICON NEWS., 2018. Koshiki Insta ‘Musashi-no-heya’ follower 12 mannin koeta-o. [Official fake account ‘Musashi’s room’ got more than 120,000 followers. [online] Available at: https://www.oricon.co.jp/news/2110839/full/ [Accessed on 3 December 2021].

- Rainbow Life, 2018. Special issue: Ossan’s Love ni aete yokatta [It was great to meet ‘Ossan’s b Love’]. [online] Available at: https://lgbt-life.com/topics/OssansLove/ [Accessed on 3 December 2021].

- Real Sound, 2018. Sexual minority no eiga ha dou hensenshita? Rainbow Reel Tokyo tantosha ni kiku [How have sexual minority themed films developed? Interview with the person in charge of Rainbow Reel Tokyo.]. [online] Available at: https://realsound.jp/movie/2018/07/post-219624.html [Accessed on 3 December 2021].

- Sabharwal, S. K. and Sen, R., 2012. Portrayal of Sexual Minorities in Hindi Films. Global Media Journal, 3(1), pp. 1–13.

- Sánchez-Soriano, J.-J. and García-Jiménez, L., 2020. The media construction of LGBT+ characters in Hollywood blockbuster movies. The use of pinkwashing and queerbaiting. Revista latina de comunicación social, 77, pp. 95–116.

- Shiller, R., 2003. The show was never written for straight women. So why is Queer as Folk making women wet?. Fab: The Gay Scene Magazine, 213, pp. 3–6.

- Suter, R., 2013. Gender Bending and Exoticism in Japanese Girls’ Comics. Asian Studies Review, 37(4), pp.546–558.

- Tabata, A., 2018. Drama Ossan’s Love no poster to catch copy ga kanpeki dato wadai ni [People are talking that the posters and the marketing copies of TV Drama Ossan’s Love are perfect]. [online] Available at: https://youpouch.com/2018/04/21/504702/ [Accessed on 3 December 2021].

- TV Asahi., 2018. The official book: Ossan’s Love. Tokyo: Bungeishunju.

- Winderman, K. and Smith, N. G., 2016. Sexual Minority Identity, Viewing Motivations, and Viewing Frequency of LGB-Inclusive Television Among LGB Viewers. Sexuality & Culture, 20, pp. 824–840.

Article Rights and License

© 2022 The Author. Published by Sprint Investify. ISSN 2359-7712. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.