Keywordsattributes patronage selection shoppers shopping centres

JEL Classification M10

Full Article

1 Introduction

Shopping centre selection has been a topic of interest for academics for many decades. However, despite the widespread investigation, it remains a topic of interest across a wide range of research topics such as marketing, business management, engineering, architecture and IT. South Africa (SA) has experienced an enormous increase in shopping centre development, numbering over 2000 shopping malls at the time of writing this paper; as such, SA has the sixth-highest number of shopping centres in the world, occupying 23 million m2 of shopping space (Innovate, 2016). Townships and rural areas are regarded as areas primed for growth because of the rapid growth in income in these areas, along with saturated retail markets in established urban areas (Aspen Networks of Developing Entrepreneurs, 2021). Consumers in rural and townships areas have a combined spending power of more than R 308 Billion annually, which represent 41 percent of total consumer spending (Eprop, 2013). The rural and township market have emerged new market for national retailers seeking growth opportunities. The expansion of shopping centres has created a wider choice of shopping destinations that can meet consumers’ needs for goods, services and entertainment (Poovalingam and Docrat, 2011), thus creating competition for shopping centres.

According to Kushwaha, Ubeja and Chatterjee (2017), a shopping centres consists of a group of retail businesses that are planned, developed, owned and managed together as a unit. Levy, Weitz and Pandit (2012) define shopping centres as “closed, climate-controlled, lighted shopping centres with retail stores on one or both sides of an enclosed walkway”. It is a commercial building that is used to accommodate the shopping activities and lifestyles of consumers while in process facilitating their socio-economic and recreational activities (Zuhri and Ghozali, 2020). Shopping centres consist of cures that involve multiple senses, including sight, smell, taste, touch and hearing, which determine if consumers will visit a mall or not (Kumar and Kashyap, 2023). How this unit is planned, developed and managed is determined by the quality of the shopping centre attributes, which differs from mall to mall. The intense competition forces shopping centre managers to create a unique and favourable image of their malls, which requires that they identify the mall attributes suitable for shopping centre selection (Singh and Dash, 2012).

Shopping centre development in SA has had a stimulating effect on the development of previously underdeveloped areas. Shopping centres have been erected throughout SA and have expanded into townships and rural areas across the nine provinces of SA. Previously, consumers in townships and rural areas would have to drive over 30 kilometres to reach the nearest shopping centre. However, this has changed; nowadays they are not far from the nearest mall. Therefore, it is important to expand on existing studies on shopping centre attributes that influence consumer selection to since they differ for different market segments (Kumar and Kashyap, 2023). Larger retailers in SA have also been expanding into previously underdeveloped areas, thus creating opportunities for shopping centre development. According to the SA Council of Shopping Centres (SACSC) (2017), the average size of shopping centres has been steadily increasing since the 1990s. This is because shopping centres aim to dominate their immediate catchment area and attract a higher proportion of national tenants, thus strengthening the centre’s position within its catchment area.

Shopping centres have become a centre of attraction for people seeking entertainment and for shopping purposes, which is why they provide an extensive range of product categories, a variety of speciality stores, as well as recreational offerings. However, some shopping centres experience serious challenges in attracting more shoppers and retailers, which leads to reduced profitability and a reduction in sales per square metre (Tsai, 2010). Iroham, OlajuAkinwale, Okagbue,. Peter and Emetere (2020) argue that shopping centre patronage leads to increased shopping rental payment, which in turn increase profitability. Although there has been a move to shopping at retailers located in shopping centres, consumers still frequent traditional stores outside shopping centres for reasons of convenience. This creates competition for shopping centres, leading them to identify attributes that can be used to position shopping centres to influence consumer choice (Competition Commission SA, 2019).

Shopping centres need to differentiate themselves from their competitors to survive and gain sustainable competitive advantages (Kursunluoglu, 2014). This requires that they identify attributes that match what shoppers consider important when selecting a shopping centre. Understanding shopping centre attributes that are important to shoppers will ensure that shopping centres are positioned accordingly and can attract the targeted shoppers (Kumar and Kashyap, 2023). Shopping centres also need to improve their offerings, attractiveness and image continually to keep up to date with new developments regarding attributes for shopping centre choice (Ortegón-Cortázar and Royo-Vela, 2017).

The SA Council of Shopping Centres (SACSC) (2020) reported the four areas which shopping centre managers can improve to attract shoppers. These include sanitation; minimizing possible visitor contact at entrances, exits and in the stores; promotional events; and offering the “shopper experience”. The latter included aspects such as security and a unique experience. This indicates the need for shopping centres to improve their entertainment and recreational offerings, as well as their experiential shopping offerings. Since most African consumers in SA still rely on public transport, especially those living in townships and rural areas, accessibility to public transport and self-propelled transport such as bicycles are a major consideration for shopping centre attraction (Busitech, 2018).

Existing studies that sought to identify shopping centre attributes identified various attributes that differ according to different locations, shoppers and across shopper demographics. This highlights the diversity of shopping centre attributes and shows that researchers do not agree on the attributes important in shopping centre selection. Gomes and Paula (2017) pointed that the differences in shopping centre attributes are a result of researchers’ using different literature sources to fit specific contexts, which creates a patchwork-type model of mall attributes. This could also be because individual shoppers place different emphasis on the importance of shopping centre attributes (Kumar and Kashyap, 2023), which calls for research on attributes important to customers across age, gender and location categories (Cvetkovic, �ivkovic and Lalovic, 2018).

The shopping centre research related to consumer choice focuses on studying the attributes that influence consumers’ buying decisions. The assumption is that consumers have a set of attributes that they consider important when they select a shopping centre and change from time to time (Borusiak, Pieranski, Florek and Mikolajczyk, 2018). Therefore, continued instigation on shopping centres is necessary to keep up to date with changes in the attributes important for shopping centre selection, especially for young consumers (Bawa, Sinha, and Kant, 2019). Shopping centres are centres of attraction for consumers who visit malls for entertainment purposes (Nthle, 2023). Consumers patronise shopping centres that best meet their needs after they have evaluated the set of attributes that they consider important in shopping (Nair, 2018). Therefore, understanding a set of attributes that consumers consider important when selecting a shopping centre helps shopping centre owners go position the mall using the attributes important to consumers (Guptaa, Mishrab and Tandon, 2020).

Existing studies have focused on various dimensions of shopping centre attributes, and they mainly focus on those attributes affecting consumers in urban areas, while excluding consumers from townships and rural areas. The fact that new shopping centres are being developed every year in SA calls for continued research on the attributes attracting consumers to a shopping centre. Consumer lifestyles also change and need a comprehensive understanding of their evolving needs (Wulandari, Suryaningsih and Abriana, 2021), and in this case, what attract them to a shopping centre. Consumer behaviour has become increasingly unpredictable due to changes in their social economic status, technological development and competition among shopping centre developers (Hasliza and Muhammad, 2012). The difficulties in predicting the attributes important in attracting consumers, especially the millennials, in shopping centres has placed calls for research on why consumers visit shopping centres (Gupta et al., 2020).

This study will therefore focus on shopping centre attributes for consumers in rural areas to determine which factors are important to them when choosing a shopping centre. Since consumers visit the shopping for various reasons, including shopping, browsing, socialising or to enjoy the shopping centre’s atmosphere and environment (Breytenbach, 2014), it is important that shopping centres attract consumers’ attention by incorporating attributes that will be favourably received by the shoppers (Park, 2016). Shopping centre managers and owners must identify shopping centre attributes relevant to their target market and formulate an appropriate their positioning (Brito,McGoldrick, and Raut (2019, 2019). This is important for them to device unique positioning strategies to attract targeted segments (Wong &Nair 2018) and to increase satisfaction and loyalty of consumers visiting the mall (Rashmi, Poojary and Deepak, 2016).

Existing studies reported demographic differences between groups of shoppers (Calvo-Porral and Lévy-Mangin, 2019; El-Adly, 2007; Kabadayi and Paksoy, 2016). Consequently, Rahmawati (2019) noted that “the differences in gender, age, status, education, and income vary widely between countries, with no specific demographic profiles being consistently identified for a specific group of shoppers”. Shopping centre managers must develop appropriate shopping centre marketing strategy relevant to the socio-demographics of their customers (Duffet and Foster, 2018). Duffet and Foster (2018) further maintain that shopping centres should take into consideration different social status and class of consumers when formulating marketing strategies. The purpose of this study was to determine the mall attributes that consumers consider when visiting a mall, as well as to determine if these attributes are influenced by demographics factors.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Theoretical Framework

The study adopted the Stimulus Organism and Response Model (S-O-R) introduced by Mehrabian and Russell (1974) as a theoretical model guiding the study. The S-O-R model has been applied widely in consumer behaviour studies (Chang, Eckman and Yan, 2011), brand management (Tan, 2020), online brand community (Rahmawati, and Kuswati, 2022), travel experience ( Chen., Fung So., Hu and Poomchaisuwan (2021), retail (Goi, Kalidas and Zeeshan, 2014) and shopping centre studies (Karim, Chowdhury, Al Masood and Arifuzzaman (2021). As stated by Mehrabian and Russel (1974), the environmental stimuli (S) that consumers are exposed to cause different types of behavioral responses (R), which can be approach or avoidance. The behaviour response occurs as a result of internal evaluations (O) to the stimuli (Harapa, 2020).

The model is relevant for this study since it investigates the stimuli, herewith regarded as the shopping centre attributes, that influence consumer decision to visit a shopping centre. The decision consumers make based on their internal evaluation of the stimuli, which are the shopping centre attributes determine their response, which can either be positive by visiting the shopping centre or negative by avoiding the shopping centre. It should be noted that consumers may respond different even though they are exposed to similar stimulus, which is why it was necessary to determine if the demographics of consumers influence the shopping centre attributes.

2.2 Shopping centre attributes

A review of the retailing literature revealed various attributes influencing consumers to visit a shopping centre, but there was no consensus on shopping centre attributes, since there are multiple attributes that include tangible and intangible aspects (North and Kotze, 2004). Earlier researchers listed diverse shopping centre attributes. Bloch et al. (1994) listed seven attributes that collectively motivate consumers to visit shopping centres, namely aesthetics, escape, flow, exploration, role enactment, social and convenience. Bearden (1977) also listed seven attributes including established location, price, parking facility, quality of merchandise, ambiance, assortment, and friendly approach by staff while Baker (2002) outlined the travel cost such as petrol and parking charges as important shopping attributes.

Wong and Nair (2018) listed child-friendliness, parking facilities and mall security/convenience followed by mall marketing activities, service offerings and convenience offered to ladies and elderly people. Jaafura (2018) added ambience of shopping malls, assortment of stores, sales promotions and comparative economic gains as important shopping centre attributes. It is important noting that some researchers focus on diverse attributes while other focusing on one important attribute as done by Iroham et al (2019) who investigated the shopping centre facilities as impact on shopping centre patronage. The variety of merchandise and the quality and status of the shopping centre proved to have the most significant effect on a shopping centre’s attractiveness (Ortegón-Cortázar and Royo-Vela, 2017). This shows that shopping centre attributes are diverse and differ for different consumer segment, countries and location of the shopping centre ( Frasquet, Gil and Molla, 2001). Gonza´lez-Herna´ndez and Orozco-Go´mez (2012) supported by Kumar and Kashyap (2023) and Koksal (2019) agree that shopping centre attributes differ for different customer segments and for different types of shopping centres. Biyase, Corbishley and Cason (2021) argued for quick response and supply chain efficiency while Stir (2018) maintained that attributes for stores and products are similar and can be argued that these attributes applies to shopping centre selection. Table 1 below summarises shopping centre attributes reported in various studies.

Table 1: Shopping mall attributes

| Study | No of factors | Factors |

| Kumar and Kashyap (2023) | 4 | Convenience, entertainment, atmosphere and architecture design |

| Saprikis, Avlogiaris and Katarachia (2021) | 6 | Enjoyment, reward, facilitating conditions, social influence, innovativeness, and trust |

| Breytenbach, 2014 | 4 | Entertainment and facilities, quality and atmospherics, convenience and way-finding and decor |

| Brito,et al. (2019) | 4 | Utilitarian: proximity, convenience and accessibility variables Hedonic: experience of feeling or emotion |

| Ying and Aun (2019) | 3 | Tenant mix, access, convenience, and ambience |

| Mansori and Chin (2019) | 6 | Communication, accessibility, convenience, tangibility, facilities, pleasure, entertainment, and product assortment |

| Kushwaha, Ubeja and Chatterjee (2017) | 7 | Service experience, internal environment, convenience, utilitarian factors, acoustics, proximity and demonstration |

| Ortegón-Cortázar and Royo-Vela (2017) | 5 | Product variety, quality, status, mobility and accessibility |

| Kabadayi and Paksoy (2016) | 7 | Aesthetics, escape, flow, exploration, role enactment, social and convenience |

| Rashmi, Poojary and Deepak, (2016) | 6 | reach ability, atmosphere, shopping experience, promotions, property management and entertainment |

| Dubihlela and Dubihlela (2014) | 7 | Merchandisers, accessibility, service, amenities, ambience, entertainment and security |

| Kursunluoglu (2014) | 6 | Location, merchandise assortment, pricing, communication, store atmosphere and customer service |

| Gudonaviciene, Sonata and Alijosiene (2013) | 8 | Accessibility, service, facilities, atmosphere, amenities, ambulance services, entertainment and security |

| Poovalingam and Docrat (2011) | 5 | Physical surroundings, social surroundings, time, task definition and antecedent states |

| Tsai (2010) | 6 | Atmospherics, product arrangement, service, mall image, special events and refreshment |

| Hedhli and Chebat (2009) | 5 | Access, price/promotion, store atmosphere, cross-category assortment and assortment within a category |

| Finn and Louviere (1996) | 6 | Merchandise, atmosphere, services, accessibility, anchor tenant and trendline |

| Bloch et al. (1994) | 7 | Aesthetics, escape, flow, exploration, role enactment, social activities and convenience |

| Hauser and Koppelman (1979) | 5 | Variety, quality, satisfaction, value and parking |

As can be seen from the table above, shopping centre attributes have been a subject of investigation for many decades. This is due to changing consumer preferences which requires that shopping centre owners and managers adapt with the changes by updating the shopping centre attributes. The table shows many different attributes that determine customers’ shopping centre selection. However, the most listed attributes are merchandise/product assortment, access and convenience, social influence, facilities/ atmospheric/ servicescape and services. Although pricing within shopping centres is less commonly mentioned among the studies, Kursunluoglu (2014) and Hedhli and Chebat (2009) reported it to be an important consideration when consumers choose a shopping centre. Gomes and Paula (2017) also listed price as one of the most cited shopping centre attributes in marketing and retail studies. Each of the abovementioned main attributes is discussed below.

Merchandise/product assortment

According to Poovalingam and Docrat (2011), the types and designs of shops within shopping malls greatly influence shopping mall patronage. This is because these aspects contribute to the ambience of the shopping mall and determine if shoppers will find it convenient or ease of use within the shopping centre. They also revealed that the merchandise/product range offered was important in attracting customers to a mall. Boatwright and Nunes (2001) suggested that consumer preferences are influenced by the perception of variety within an ensemble of selection choices, while Khei et al. (2001) considered quality and variety to be the most critical attributes to measure shopping centre. Quality and variety refer to both the shops available and the offers and/or merchandise/products (Dubihlela and Dubihlela, 2014). This also includes store variety, the presence of various products and well-known brands, as well as the quality of the products and the presence of exclusive and prestigious clothing brands (Ortegón-Cortázar and Royo-Vela, 2017).

Access and convenience

Mall convenience is one of the most important attributes for shopping mall attractiveness since it involves the accessibility of the mall for the shoppers (Ahmad, 2012). Some consumers are anti-shopping (Ahmed et al., 2007), spending little time and making few purchases at the mall (Loudon and Bitta, 1993). Other consumers are time-constrained and prefer to shop at a convenient location (Pan and Zinkhan, 2006; Loudon and Bitta, 1993). Mall access is determined by the ease of getting in and out of a shopping centre (Levy and Weitz, 1998) and includes aspects such as accessible roads (Chebat et al., 2010), how closely the mall is located to the customer’s place of work or residence and how easily available the parking facilities are within the centre (Gudonaviciene and Alijosiene, 2013; Frasquet et al., 2001). Lucia-Palacios, Raúl Pérez-Lopez and Polo-Redondo (2019) argue that shopping centre managers should take stress level of consumers who visit the mall and consider it when formulating marketing strategies. Furthermore, Soomro, Kalwar, Memon, and Bakar Kalwa (2021) argue that the inaccessibility of the mall influences the frequency of mall visit by consumers. This is supported by Lloyd, Chan, Yip and Chan (2014) who presented that the influence of convenience on mall attractiveness depend on the economic value consumers place on time and that those consumers with high economic value on time perceive service convenience as having greater impact than those without.

Consumers also want to satisfy different needs in one place (Yin and Aun, 2013). The main aim is for consumers to save time and minimise effort when accessing the shopping mall (Seiders et al., 2007; Yin and Aun, 2013). For those shoppers relying on public transport the accessibility of public transport to shopping malls and the convenience of navigation are important factors (Dubihlela and Dubihlela, 2014). Ultimately, the mall should enable shoppers to complete their shopping tasks with minimal time and effort. (El-Adly and Eid, 2015; Pan and Zinkhan, 2006).

Social influence

Social influence is an important factor in determining shopping centre patronage and satisfaction (Okoro, Okolo and Mmamel, 2019) because shopping centres create opportunities for social interactions outside the home; shoppers can meet new acquaintances at the mall or meet and visit with family and friends (Tiwari and Abraham, 2010) Shopping centres are a place for people to meet and socialise with friends – an activity that is particularly common among teens who visit a shopping centre to for lecture purposes and for recreational activities (Wulandari, et al., 2021). The shopping centre should be designed such that the recreational facilities and activities influences consumer desire to stay at the mall (Elmashhara and Soares, 2020).

Shopping centre atmosphere/servicescape

This involves the physical environment of an organisation, including aspects such as design and decoration. Juhari, Ali and Khair (2012) listed three dimensions of atmosphere, namely ambience, space layout and signage, and symbols and artefacts. The signage or directions and the décor are tools used to communicate with the customers. They help customers to locate a store that they want to visit, and they can add character, beauty and uniqueness to the image of the shopping centre (Levy and Weitz, 2004). The atmospheric has been researched by various authors, who have reported on the influence it has on consumers visiting the shopping centre (Wulandari, et al., 2021). Pereira et al. (2010) found that the effect of atmosphere, on shopping centre patronage differs across gender and that men place different value on the components of visual merchandising within stores, specifically the window display lighting and visualisation of the display from inside the store. Nevertheless Cernikovait et al. (2021) did not find a significant correlation between atmospherics and shopping centre attractions. Faria, Carvalho and Vale (2022) support the importance of store/mall design and that it influence consumer satisfaction.

Service facilities

Facilities refer to communal services, such as facilities for disabled people, emergency services, safety and security services, as well as other services such as escalators, lifts and signboards. They also include amenities (such as restrooms), as proposed by Berman and Evans (2001) and Lovelock, Patterson and Walker (1998). According to Tongue, Otieno and Cassidy (2010), the basic amenities play an important role in the decision-making process of consumers, while the absence of such services adversely affects consumers (Frimpong, 2008). The presence of support facilities enhances the service experience of the shoppers (Kushwaha et al., 2017) and customers’ experience is affected by the interaction between the customers and the employees (Bitner, 1992). Kursunluoglu (2014) refers to services as facilitative activities to customers and reported that they do not influence customer satisfaction with the shopping mall. Lee et al. (2005) regards the facilities as value-added facilities and state that they moderately influence consumers’ attraction to shopping malls. Iroham, Akinwale, Oluwunmi, Okagbue, Durodola, Ayedun, and Peter (2019) identified four categories of facilities such as recreation, children banking and health as having a great influence on shopping centre patronage.

Pricing

Prices at shopping centres were reported to affect the choice of shoppers’ patronage. It is believed that shopping centres with stores that charge lower prices are frequented more often by the majority who are price conscious (Poovalingam and Docrat, 2011). However, Mahin and Adeinat (2020) stated that price did not have any significant relationship with customer satisfaction when visiting the food court at a shopping centre. Instead, the availability of a wide variety of stores in terms of quality and pricing was an important determinant of shopping centre patronage (Khurana and Dwivedi, 2017).

Although satisfaction with visiting a shopping centre is not a shopping centre attribute it is important to determine consumer satisfaction with the shopping centre. The reason for this is that consumer satisfaction determines if the consumers will visit the mall again. Shopping centre managers and owners must strive to ensure that consumers are satisfied with their visit to the mall and that they may remail loyal to the shopping centre. Mahin and Adeinat (2020) state that it is important to identify shopping centre attributes that influence consumer satisfaction. Ahmad (2012) identified shopping centre attributes influencing consumer satisfaction and listed convenience and accessibility, product variety, entertainment, and service quality. Wong, Hing, Ng, Wong and Wong (2012); supported by Albattata, Yajida and Khatibi (2019) maintained that different factors influence satisfaction. Jackson-Macon and Ogbeide (2020) added that destination attractiveness differ between Generation Y and Z, which requires that shopping centre managers consider demographic factors when positioning a shopping centre.

2.3 Conceptual model development and hypotheses formulation

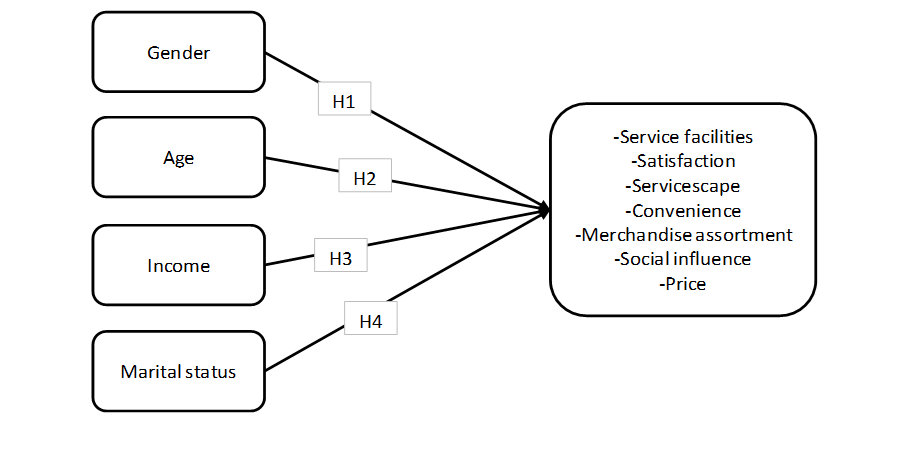

Since shopping centres are locations for retail stores, it is important to determine the demographic characteristics of shoppers visiting these centres to position the shopping centres accordingly and to plan the retail mix. The sustainability of shopping centres depends on the value that these centres can derive by servicing the final consumer. According to Rahmawati (2019), age, gender and the occupation of consumers are critical factors in their choice of a shopping centre, since consumers differ depending on their demographic characteristics. Existing studies that investigated shopping mall attributes across demographic factors found that there are demographic differences among shoppers. It is therefore important to identify the demographic characteristics of shoppers (Calvo-Porral and Lévy-Mangin, 2019; Kabadayi and Paksoy, 2016), since the demographic factors of consumers have an impact on how they evaluate shopping malls. Prasad and Arsasri (2011) state that demographic factors such as age, gender, education, occupation, income and family size influence consumer choices. The focus of this study was to determine if the shopping centre/mall attributes are influenced by demographic factors. The hypotheses tested in this study appear in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1:Proposed model

Gender and mall attributes

A study by Olonade, Busari, Idowu, Imhonopi, George and Adetund (2021) confirmed that shopping centre attributes differ across gender and age and that these demographic factors play an important role in determining consumers’ attitudes towards shopping in malls. Khare (2011) further stated that the shopping centre attributes influencing shopping centres are decor, layout, services, variety of stores and entertainment facilities; all these must be considered when planning malls in smaller cities as they affect consumers’ buying behaviour. Rahmawati, (2019) proposed that shopping centres include retail stores that are targeted to both male and female customers, since this is important for consumer choice. Olonade, et al., (2021) revealed that women visit shopping centres to purchase goods, meet new people and enjoy the beautiful ambience, while male consumers visit malls for recreational activities. Sohail (2015) supported by Mihic and Milakovic (2017) confirmed the effects of gender on the relationship between the shopping enjoyment and word of mouth. Against this background, hypothesis 1 was formulated as follows:

H1 Gender has a statistically significant influence on mall attributes in South Africa.

Age and mall attributes

Cvetkovic et al. (2018) stated that youth leisure is widely associated with shopping centres since youth seek recreational shopping, attendance at various leisure venues and events, but also browsing around when visiting shopping centres. Ahmed et al. (2007) found that students frequent shopping centres and visit more than six stores retail stores during their visits, which implies that mall merchandise is important for young consumers. More than the older respondents, these students considered the interior design of the mall; products that interest them; good alternatives for socialising with friends; and convenient one-stop shopping as important factors when visiting a mall for escapism. Rousseau and Venter (2014) stated that it would be more beneficial to shopping centres if they prioritised aspects such as adequate parking facilities, special discounts for elderly consumers and a wider variety of goods. Rahmawati (2019) reported that hedonic shoppers are mainly young consumers who are single and female; this segment of consumers is driven by gratification seeking, social shopping, value shopping and brand loyalty. Parker et al. (2019) and Dhiman et al. (2018) also reported differences in the importance of store attributes among different age groups. Based on this discussion, the next hypothesis was formulated as follows:

H2 Age has a statistically significant influence on mall attributes in South Africa.

Income and mall attributes

The Competition Commission SA (2019) found that consumers in different income bands generally spread their shopping across different outlets, which suggests that consumers might not be loyal to just one shopping centre. It was further reported that lower-income consumers do their weekly or monthly shopping outside their local area, which means that shopping centres should design shopping centres to possess mall attributes that will keep consumers at their local centres. Makhitha and Mbedzi (2021) established that income influences choice, and this was supported by Verma et al. (2015). However, Mahlangu and Makhitha (2019) reported that income does not have a significant influence on consumer choice. Therefore, the next hypothesis was formulated as follows:

H3 Income has a statistically significant influence on mall attributes in South Africa.

Marital status and mall attributes

Witek et al. (2021) reported that marital status influences the attributes that consumers consider when making a choice of where to shop. This confirmed the finding by Mahlangu and Makhitha (2019). It was also confirmed by Armaganm, Tokmak and Dikici (2017), Varadaraj and Charumathi (2019) and Özkan (2020), namely that marital status affects the attributes considered by consumers when making a choice of where to shop. Melkis, Hilmi and Mustapha (2014) came to the same conclusion, claiming that marital status has an influence on time spent and that married people are motivated by different factors from those of unmarried couples. Hence the following hypothesis:

H4 Marital status has a statistically significant influence on mall attributes in South Africa.

3 Research Methodology

The research design used for this study was a quantitative survey. A survey was found to be most appropriate since it allows researchers to target a larger population size allowing the findings to be quantified. Existing studies on shopping centre attributes also used a quantitative survey, which also influenced the researcher in to adopt a quantitative survey for this study. A survey was also deemed appropriate since shoppers were expected to select the most suitable responses from the options provided (Babbie and Mouton, 2001).

A convenience sampling method was used for this study since it is cost-effective (Cooper, 2006). Data were collected from the mall in Venda, thus targeting consumers that visited the mall during the data collection period. Shoppers were intercepted when leaving the mall to ensure that data collection did not interrupt consumers when entering the mall and that shoppers had finished their shopping. The questionnaire was handed to the shoppers, and they were required to complete it unaided. The cover letter for the questionnaire explained to shoppers that completing the questionnaire was voluntary and that they could choose not to complete it. Field workers distributed over 300 questionnaires, but only 223 were completed fully completed. The remaining questionnaires were either incomplete or were not completed at all and were therefore discarded.

Data were analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 27 for Windows. The statistical analyses used for the study were descriptive statistics, factor analysis, t-test and ANOVA to determine the demographic differences in relation to shopping centre attributes.

4 Results and Discussions

Most of the sample respondents were male (59.2%, n=125). More than two-thirds (37.7%, n=84) of the respondents were between 18 and 24 years old. The 60–65-year-old group had only three (3) respondents (1.3%). More than 75% of the respondents were unmarried (77.2%, n=169). A large proportion of the sample (60.8%, n=135) had post-school qualifications, while more than one-third of the respondents (35.7%, n= 79) were students. Three respondents indicated an occupation not listed in the questionnaire (see Table 1 below). The largest proportion of the respondents (45.7%, n=101) earned R2 500 or less per month. The respondents typically tended to buy infrequently (31.1%, n=68) and monthly (30.1%, n=66), with very few of them buying weekly (2.3%, n=5). Taxis (43.7%, n=97) were the most popular means of transport among the respondents, followed by “own vehicle” (25.7%, n=57). The largest proportion of respondents spent 1.5 to two hours (36.4%, n=82) at the mall and another 30.2% (n=68) spent two to four hours at the mall. Most respondents (80.4%, n=181) visited one to two malls and almost 30% (29.3%, n=66) of the respondents visited three to four stores per shopping centre visit.

Table 1: Demographics

| Demographics | Description | Population | Percentages |

| What is your gender? | Male | 125 | 58.7% |

| Female | 86 | 40.4% | |

| 4 | 1 | 0.5% | |

| 5 | 1 | 0.5% | |

| TOTAL | 213 | 100.0% | |

| What is your age? | 18 - 24 years | 84 | 37.7% |

| 25 - 29 years | 60 | 26.9% | |

| 30 - 40 years | 51 | 22.9% | |

| 41 - 50 years | 14 | 6.3% | |

| 51 - 59 years | 11 | 4.9% | |

| 60 - 65 years | 3 | 1.3% | |

| TOTAL | 223 | 100.0% | |

| What is your marital status? | Married | 50 | 22.8% |

| Unmarried | 169 | 77.2% | |

| TOTAL | 219 | 100.0% | |

| What is your net income per month? | 0 - R2 500 | 101 | 45.7% |

| R2 501 - R5 000 | 39 | 17.6 | |

| R5 001 - R7 500 | 20 | 9.0% | |

| R7 501 - R12 500 | 11 | 5.0% | |

| 12 501 - R20 000 | 30 | 13.6% | |

| Over R20 001 | 20 | 9.0% | |

| TOTAL | 221 | 100.0% |

4.1 Reliability and validity

The Cronbach alpha was used to determine the reliability of the constructs. According to Hair (2010) a Cronbach alpha of 0.70 and above signifies acceptable reliability. Therefore, the Cronbach alpha for each of the constructs was deemed reliable, with the satisfaction construct having a Cronbach alpha of 0.86; service (0.86); mall facilities (0.85); convenience (0.84); merchandise assortment (0.79); social influence (0.83); and price (0.80). The overall reliability for all the constructs was 0.95.

The validity of the study was determined in more than one way. First, the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) (see table 1 below) was conducted, which grouped items together producing seven factors. The communities were also used to determine validity, as communalities above 0.26 signify validity (Child, 2006). For this study, the communalities ranged from 0.55 to 0.78. The correlation coefficients among the constructs were also strong, with values ranging from 0.386 to 0.667. According to Hox et al. (2017) and Kline (2011:74), the correlation coefficients must be less than 1.0, which signifies convergent validity.

4.2 Factor analysis and importance of mall attributes

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA), using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with IBM SPSS Statistics 27, was conducted to reduce the dimensionality of the data and to examine patterns of correlations among the questions used to reveal the reasons were for selecting a shopping mall. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was 0.912, far above the recommended minimum value of 0.6 (Kaiser, 1970, 1974) and the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (Bartlett, 1954) reached statistical significance, p<.001. Thus, the correlation matrix was deemed factorable. Of the 44 items that were initially subjected to PCA, nine of the variables had to be excluded from the solution since they were not contributing to the solution for various reasons, namely items loading equally effectively on more than one factor, one item loading alone on a factor, items not loading on any factor with a loading ≥.4 and factors with only two items that were not well correlated. The remaining 35 items resulted in a 7-factor solution, explaining 65.69% of the variation in the data, as can be seen in table 2 below.

Table 2: Mall shopping factor analysis

| Mall attributes | Factor 1: Satisfaction | Factor 2: Convenience | Factor 3: Servicescape | Factor 4: Service facilities | Factor 5: Merchandise | Factor 6: Social influence | Factor 7: Price |

| The shopping centre meets my expectations | .863 | ||||||

| I am a loyal customer of this shopping centre | .759 | ||||||

| The shopping centre is my ideal place | .748 | ||||||

| I would certainly recommend this shopping centre to my friends | .656 | ||||||

| I am very satisfied with the shopping centre | .636 | ||||||

| The cleanliness of the shopping centre | .925 | ||||||

| The shopping centre has convenient hours of operation. | .817 | ||||||

| There are adequate parking facilities available. | .682 | ||||||

| The shopping centre is easily accessible from the parking area. | .628 | ||||||

| The level of security in the shopping centre is high. | .588 | ||||||

| The shopping centre has adequate luxury products/items. | .559 | ||||||

| The shopping centre is highly recommended by others. | .799 | ||||||

| The shopping centre has informative product descriptions. | .783 | ||||||

| The shopping centre has attractive product displays. | .765 | ||||||

| The shopping centre has an adequate assortment of brands. | .645 | ||||||

| The shopping centre has favourable media reports. | .577 | ||||||

| The shopping centre has a children’s play area. | .552 | ||||||

| It is easy to locate a desired store at the shopping centre | .813 | ||||||

| There are facilities for disabled people | .757 | ||||||

| The shopping centre is a one-stop destination | .649 | ||||||

| The shopping centre offers high-quality services | .646 | ||||||

| The staff at the shopping centre are friendly | .510 | ||||||

| The shopping centre provides emergency services | .418 | ||||||

| The shopping centre provides a wide variety of shops | .781 | ||||||

| The shopping centre is close to where I live/work. | .777 | ||||||

| Safety and security measures are adequate. | .732 | ||||||

| A wide variety of services are available at the shopping centre, e.g. restaurants, hair salons and banks. | .683 | ||||||

| The shopping centre makes it easy to mingle with interesting people | .757 | ||||||

| I can easily hang out with friends while at the shopping centre | .721 | ||||||

| The mall has a good reputation | .618 | ||||||

| The shopping centre is good for spending time with family | .548 | ||||||

| The shopping centre offers special discounts and promotions | .890 | ||||||

| The shopping centre provides affordable products/items. | .840 | ||||||

| The shopping centre is easily accessible when using public transport | .506 | ||||||

| It feels safe to shop at the shopping centre | .488 | ||||||

| Mean score | 4.17 | 4.34 | 4.20 | 4.17 | 4.25 | 4.24 | 4.28 |

| Standard deviation | 0.68 | 0.60 | 0.66 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.68 |

It can be seen from the above table that all factors had factor loading of 0.4 and above. Factor 2, which was named Convenience and factor 7, names price were deemed most important attributes for shoppers visiting a shopping centre with a mean score of 4.38 (SD=0.66) and 4.25 (SD=0.68) respectively followed by factor 5, namely merchandise, and factor 6, namely social influence, with mean scores of 4.25 (SD=0.66) and 4.25 (SD=0.64), respectively. The standard deviation for each of the factors was low, which shows that the shoppers mostly agree on the importance of each of the attributes. From the above table, it can be concluded that convenience is a more important shopping centre attribute for consumers than are other attributes, as shown by a high mean score of M= 4.28, followed by price (M=4.25) and social influence (M=4.24). It can also be said that all the above shopping centre attributes are important to shoppers since they all have a high mean score of above 4. Factors 3 and 4 are equally rated, with mean scores of 4.17, which implies that satisfaction and servicescape attributes are also important to consumers since the scores were both above 4.

Calvo-Porral and Lévy-Mangín (2018) reported that convenience do not influence shopping mall visitation. Kumar and Kashyap, (2023) revealed that different mall segments from emerging markets consider the variety and availability of apparels as well as price (discounts and offers) as more important attributes as they prefer to buy products at discounted prices.

4.3 Testing the Hypotheses

There were five hypotheses formulated for this study, linked to gender, age, marital status, frequency of purchase and income. The results of these hypotheses are presented and discussed below.

Gender and mall attributes

To determine whether gender has a significant effect on whether the respondents consider the different shopping centre to be a reason for them to select a mall, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was used.

Table 3: Gender and mall attributes test statistics

| Satisfaction | Access and convenience | Servicescape | Service facilities | Merchandise | Social influence | Price | |

| Mann-Whitney U | 4614.500 | 5079.000 | 4300.000 | 4656.000 | 4147.500 | 4425.500 | 4917.000 |

| Wilcoxon W | 12240.500 | 12705.000 | 11926.000 | 12282.000 | 11528.500 | 11685.500 | 12420.00 |

| Z | -1.040 | -.492 | -2.312 | -1.480 | -2.261 | -1.502 | -.208 |

| Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) | .298 | .623 | .021 | .139 | .024 | .133 | .835 |

Gender has a significant effect on whether the respondents consider shopping centre servicescape (Z=-2.312, p<.05) and shopping centre merchandise (Z=-2.261, p<.05) to be reasons for them to select a shopping centre. On average, females (MR =116.50, n=86) tend to indicate shopping centre facilities as a reason to select a shopping centre significantly more often than do males (MR=96.96, n=123). On average, females (MR=114.13, n=84) tend to indicate shopping centre merchandise as a reason to select a shopping centre significantly more often than do males (MR=95.28, n=121). Cernikovait et al. (2021) could not confirm a significant correlation between servicescape and shopping centre attractions. Perreira et al. (2010) confirmed that the influence of servicescape differs according to the gender of shoppers. Wong and Nair (2018) also reported that shopping centre servicescape is important for consumers when visiting a shopping centre and that it differs according to gender. Khare (2011) agreed that shopping centre merchandise variety influences whether consumers visit a shopping centre. Furthermore, Rousseau and Venter (2014) confirmed that shopping centre merchandise influences consumers’ shopping centre patronage. Olonade et al. (2021) believed shopping centre attributes differ according to gender and reported that men visit shopping centres for recreational activities, while women visit shopping centres to purchase goods, meet new people and enjoy the beautiful ambience. However, the results of the study by Dubihlela and Dubihlela (2014) and Breytenbach (2014) contradict the study findings since they mentioned that gender has no effect on consumers’ preference for certain shopping centre attributes.

Age and mall attributes

To determine whether age has a significant effect on whether the respondents consider the different attributes to be a reason for them to select a shopping centre, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used.

Table 4: Age and mall attributes test statisticsa,b

| Satisfaction | Access and convenience | Servicescape | Service facilities | Merchandise | Social influence | Price | |

| Kruskal-Wallis H | 6.992 | 7.320 | 13.166 | 10.020 | 4.432 | 1.919 | 5.496 |

| df | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Asymp. Sig. | .136 | .120 | .010 | .040 | .351 | .751 | .240 |

| a. Kruskal-Wallis test | |||||||

| b. Grouping variable: q6_Age What is your age? | |||||||

The Kruskal-Wallis test found that age has a significant effect on whether the respondents consider mall servicescape (H(4)=13.166, p<.05) and shopping centre service (H(4)=10.020, p<.05) to be reasons for them to select a mall. The post-hoc test was conducted to determine where the differences lay among the age groups regarding shopping centre servicescape. The 50-year-old group (MR=139.25, n=14) agreed significantly more that mall servicescape is a reason for selecting a shopping centre than did the 18–24-year-old group (MR=97.42, n=84). In addition, the 41–50-year-old group (MR=151.71, n=14) agreed significantly more that mall servicescape is a reason for selecting a shopping centre than did the 18–24-year-old group (MR=97.42, n=84) and the 30–40-year-old group (MR=106.94, n=51). This is shown in tables 4 and 5.

Table 5: Mall facilities: Pairwise comparisons of q6_Age What is your age?

| Sample 1 - Sample 2 | Test statistic | Std error | Std test statistic | Sig. | Adj. Sig.a |

| 18–24 years (N=84)-30– 40 years (N=51) | -9.525 | 11.289 | -.844 | .399 | 1.000 |

| 18–24 years (N=84)25– 29 years (N=58) | -20.178 | 10.856 | -1.859 | .063 | .631 |

| 18–24 years (N=84)>older than 50 years (N=14) | -41.833 | 18.357 | -2.279 | .023 | .227 |

| 18–24 years (N=84)>41– 50 years (N=14) | -54.298 | 18.357 | -2.958 | .003 | .031 |

| 30–40 years (N=51) 25– 29 years 9N=58) | 10.654 | 12.207 | .873 | .383 | 1.000 |

| 30–40 years (N=51)-older than 50 years | -32.309 | 19.187 | -1.684 | .092 | .922 |

| 30–40 years (N=51)-41–50 years (N=14) | -44.773 | 19.187 | -2.334 | .020 | .196 |

| 25–29 years-older than 50 years | -21.655 | 18.936 | -1.144 | .253 | 1.000 |

| 25–29 years (N=58)-41– 50 years (N=14) | -34.119 | 18.936 | -1.802 | .072 | .716 |

| Older than 50 years (N=14)- 41–50 years (N=14) | 12.464 | 24.035 | .519 | .604 | 1.000 |

Note: Each row tests the null hypothesis that the sample 1 and sample 2 distributions are the same. Asymptotic significances (2-sided tests) are displayed. The significance level is .050.

The post-hoc test was conducted to determine where the differences lie among the age groups regarding the service attribute. The 50-year-old group (MR=152.46, n=14) agreed significantly more than did the 18–24-year-old group (MR=101.35, n=84), the 30–40-year-old group (MR=106.24, n=51) and the 25–29-year-old group (MR=113.76, n=58) that service is a reason for selecting a shopping centre, as can be seen in table 5.

Table 6: Service: Pairwise comparisons of q6_Age What is your age?

| Sample 1 - Sample 2 | Test statistic | Std error | Std test statistic | Sig. | Adj. Sig.a |

| 18–24 years (N=84)- 30–40 years (N=51) | -4.890 | 11.288 | -.433 | .665 | 1.000 |

| 18–24 years N=84)- 25–29 year (N=58)s | -12.413 | 10.856 | -1.143 | .253 | 1.000 |

| 18–24 years 9N=84)- 41–50 years (N=14) | -32.048 | 18.357 | -1.746 | .081 | .808 |

| 18–24 years (N=84)- older than 50 years (N=14) | -51.119 | 18.357 | -2.785 | .005 | .054 |

| 30–40 years (N=51)- < 25–29 years (N=58) | 7.523 | 12.207 | .616 | .538 | 1.000 |

| 30–40 years (N=51)- 41–50 years (N=14) | -27.158 | 19.187 | -1.415 | .157 | 1.000 |

| 30–40 years (N=51)- older than 50 years (N=14) | -46.229 | 19.187 | -2.409 | .016 | .160 |

| 25–29 years (N=58)- < 41–50 years | -19.634 | 18.936 | -1.037 | .300 | 1.000 |

| 25–29 years (N=58)- older than 50 years (N=14) | -38.706 | 18.936 | -2.044 | .041 | .409 |

| 41–50 years (N=14)- older than 50 years (N=14) | -19.071 | 24.035 | -.793 | .427 | 1.000 |

Note: Each row tests the null hypothesis that the sample 1 and sample 2 distributions are the same. Asymptotic significances (2-sided tests) are displayed. The significance level is .050.

The above results differ from those of Khare (2011), who found that the younger generation (aged between 20 and 30 years) visits shopping centres for entertainment, services, recreational, social and exploration purposes. Khare (2011) further stated that the older generation is attracted by shopping centre merchandise variety and shopping centre service, which support this study’s findings. Rousseau and Venter (2014) further expand that support shopping centre attributes differ according to different age groups, which implies that shopping centre managers should incorporate different shopping centre attributes to attract people of different age groups. Bawa et al (2019) reported that young consumers were motivated mainly by convenience, choice, awareness, crowded/congested, ambience, parking, hedonic shopping and mall culture. This proves that shopping centre attributes do differ across age groups.

Income and mall attributes

To determine whether income has a significant effect on whether the respondents consider the different attributes to be a reason for them to select a mall, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used. The Kruskal-Wallis test found that there were no significant differences among the different income groups regarding any of the shopping centre attributes, as shown in Table 7 below. This study’s findings are supported by earlier studies that reported that income does not influence attributes influencing consumer choice (Mahlangu and Makhitha, 2019; Makhitha, 2014). However, a study by Verma et al. (2015) does not support the findings of this study since they reported that shopping centre attributes are influenced by their income.

Table 7: Income and mall attributes

| Ranks | |||

| q10_Income What is your net income per month? | N | Mean Rank | |

| Mall satisfaction | 0 - R2 500 | 98 | 99.13 |

| R2 501 - R5 000 | 38 | 106.20 | |

| R5 001 - R7 500 | 18 | 121.36 | |

| R7 501 - R12 500 | 11 | 98.27 | |

| 12 501 - R20 000 | 30 | 113.97 | |

| Over R20 001 | 18 | 130.89 | |

| Total | 213 | ||

| Mall service | 0 - R2 500 | 101 | 95.91 |

| R2 501 - R5 000 | 38 | 117.04 | |

| R5 001 - R7 500 | 20 | 126.98 | |

| R7 501 - R12 500 | 11 | 122.18 | |

| 12 501 - R20 000 | 30 | 124.23 | |

| Over R20 001 | 19 | 123.42 | |

| Total | 219 | ||

| Mall facilities | 0 - R2 500 | 101 | 99.17 |

| R2 501 - R5 000 | 38 | 120.89 | |

| R5 001 - R7 500 | 20 | 122.23 | |

| R7 501 - R12 500 | 11 | 130.32 | |

| 12 501 - R20 000 | 30 | 117.07 | |

| Over R20 001 | 19 | 109.97 | |

| Total | 219 | ||

| Mall convenience | 0 - R2 500 | 101 | 102.12 |

| R2 501 - R5 000 | 38 | 118.09 | |

| R5 001 - R7 500 | 20 | 117.50 | |

| R7 501 - R12 500 | 11 | 101.95 | |

| 12 501 - R20 000 | 30 | 114.82 | |

| Over R20 001 | 19 | 124.84 | |

| Total | 219 | ||

| Mall merchandise | 0 - R2 500 | 100 | 101.82 |

| R2 501 - R5 000 | 38 | 100.11 | |

| R5 001 - R7 500 | 19 | 108.00 | |

| R7 501 - R12 500 | 11 | 139.14 | |

| 12 501 - R20 000 | 30 | 120.55 | |

| Over R20 001 | 18 | 125.08 | |

| Total | 216 | ||

| Mall social | 0 - R2 500 | 96 | 103.61 |

| R2 501 - R5 000 | 38 | 119.99 | |

| R5 001 - R7 500 | 18 | 126.69 | |

| R7 501 - R12 500 | 11 | 94.27 | |

| 12 501 - R20 000 | 29 | 94.76 | |

| Over R20 001 | 19 | 94.42 | |

| Total | 211 | ||

| Mall price | 0 - R2 500 | 98 | 99.22 |

| R2 501 - R5 000 | 38 | 116.53 | |

| R5 001 - R7 500 | 20 | 112.40 | |

| R7 501 - R12 500 | 11 | 128.64 | |

| 12 501 - R20 000 | 30 | 110.68 | |

| Over R20 001 | 18 | 115.81 | |

| Total | 215 | ||

Marital status and mall attributes

To determine whether marital status has a significant effect on whether the respondents consider the different attributes to be a reason for them to select a shopping centre, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used. The Kruskal-Wallis test found that marital status does not have a significant influence on consumers’ reasons for selecting a mall, as shown in Table 8 below. The study’s findings are contradicted by Makhitha and Mbedzi (2022), who found that marital status has a significant impact on consumer choice. Other studies also confirmed the effect of marital status on the importance of shopper attributes (Mahlangu and Makhitha, 2019; Witek et al., 2021).

Table 8: Marital status and Mall attributes

| Ranks | ||||

| q7_Marital Status What is your marital status? | N | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | |

| Mall satisfaction | Married | 49 | 115.38 | 5653.50 |

| Unmarried | 164 | 104.50 | 17137.50 | |

| Total | 213 | |||

| Mall service | Married | 50 | 122.04 | 6102.00 |

| Unmarried | 167 | 105.10 | 17551.00 | |

| Total | 217 | |||

| Mall facilities | Married | 50 | 117.05 | 5852.50 |

| Unmarried | 167 | 106.59 | 17800.50 | |

| Total | 217 | |||

| Mall convenience | Married | 50 | 117.44 | 5872.00 |

| Unmarried | 167 | 106.47 | 17781.00 | |

| Total | 217 | |||

| Mall merchandise | Married | 49 | 122.47 | 6001.00 |

| Unmarried | 164 | 102.38 | 16790.00 | |

| Total | 213 | |||

| Mall social | Married | 49 | 104.66 | 5128.50 |

| Unmarried | 161 | 105.75 | 17026.50 | |

| Total | 210 | |||

| Mall price | Married | 49 | 119.81 | 5870.50 |

| Unmarried | 163 | 102.50 | 16707.50 | |

| Total | 212 | |||

5. Recommendations, Conclusion and Limitations

In this study the researcher investigated shopping centre attributes. The results indicated that convenience, followed by price, merchandise and social influence are important shopping centre attributes. Shopping centre managers must create a holistic shopping experience for consumers by incorporating the relevant attributes into their marketing strategies for the shopping centre. This study is important for the expansion of shopping centres in SA into rural areas, since data were collected from a regional shopping centre located in a rural area of Venda, SA. This is so because shopping centre preferences for different consumer segments and locations. The fact that price was considered the most important shopping centre attribute in this study could be attributable to the shopping centre’s location in a rural area, where consumers have less income than those in urban areas. Therefore, shopping centre managers must consider retail tenant mix, being sure to include shops selling at lower prices and able to grant discounts to consumers. Ensuring a variety of merchandise is also crucial for consumers since it allows them to shop for a variety of items and thus fulfil various needs in one location. Shopping centres have also become a meeting place for people, thus enabling them to fulfil their social needs. Therefore, the design of the shopping centre and the servicescape facilitate socialisation.

The study also found that shopping centre attributes differ according to gender, age and frequency of purchase, but that the preference for certain attributes did not differ according to consumers’ income and marital status. Therefore, shopping centre managers should ensure that attributes that attract both genders are incorporated into their retail marketing strategies to ensure that both genders are satisfied with the mall. Since the preferences for certain shopping centre attributes also differ according to age groups, shopping centre managers must ensure that the attributes important to different age groups are part of their retail marketing strategies. This will ensure that all the shoppers visiting the mall as part of a family or group will be enticed by certain attributes, since the attributes important to them are part of the retail marketing strategy.

This study contributes theoretically to the existing body of knowledge. The study investigates shopping centre attributes for rural consumers, which has not been done before. However, the findings as reported above demonstrate that the shopping attributes for rural consumers are similar to those of some urban consumers since they also reported convenience, price, merchandise and social influence as important shopping centre attributes. Rural consumers are price sensitive, which is why price is regarded as the 2nd most important attributes in this study. The study also determined if shopping centre attributes differ for consumers with different demographics factors. The findings support some of the existing studies that proved that demographics influence shopping centre attributes and also agree that some of the demographics factor have no influence on shopping centre attributes.

This study focused on consumers in one shopping centre in Venda, SA. Therefore, the results of this study should not be generalised to shoppers across the country and should be interpreted with the specific location in mind. Future studies could target shopping centres across the country and could also compare shopping centre attributes for consumers in different areas, such as urban versus rural areas. Future studies could also compare attributes in terms of consumers in the different provinces of SA. Finally, future studies could focus on specific market segments, such as Gen Z consumers, to determine if Gen Z and Gen X consumers have different preferences for shopping centre attributes.

---

Conflicts of Interest: The author states that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmad, A.E.M.K., 2012. Attractiveness factors influencing shoppers’ satisfaction, loyalty, and word of mouth: an empirical investigation of Saudi Arabia shopping malls. International Journal of Business Administration, 3(6), pp. 101-112.

- Ahmed, Z.U., Ghingold, M. and Dahari, Z., 2007. Malaysian shopping mall behavior: an exploratory study. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 19(4), pp. 331-348.

- Armağan, E.A., Tokmak, M. and Dikici, G., 2017. Hedonic consumers’ consumption: causes of differences in terms of socio-demographic characteristics: a survey on consumers living in Nazilli. Research on Communication, pp. 29-42.

- Aspen Networks of Developing Entrepreneurs. 2021. Ecosystem snapshot: South Africa township economy. [Online] Available at: https://ecosystems.andeglobal.org/snapshot/south-africa-township-economy/2021/ [Accessed on 5 June 2023].

- Berman, B. and Evans, J., 2001. Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, 8th ed. Prentice Hall, United States.

- Bernardo, V., Da Silva, M.F., Miguel, R. and Lucas, J., 2010. The effect of visual merchandising on fashion stores in shopping centres. 5th international textile, clothing and design conference – Magic World of Textiles, 3-6 October 2010, Dubrovnik, Croatia.

- Bitner, M.J., 1992. Servicescapes: the impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), pp. 69-82.

- Biyase, N., Corbishley, K. and Mason, R.B., 2021. Quick Response and the Supply Chain in Fast Fashion in South Africa: A Case Study. Expert Journal of Marketing, 9(2), pp.66-81.

- Bloch, P.H., Ridgway, N.M. and Dawson, S.A., 1994. The consumer mall as shopping habitat. Journal of Retailing, pp. 23-42.

- Boatwright, P. and Nunes, J., 2001. Reducing assortment: an attribute-based approach. Journal of Marketing, 65(3), pp.50-63.

- Breytenbach, A. 2014. Black consumers’ shopping patronage and perceptions of Riverside mall’s attractiveness. Thesis, University of Pretoria.

- Brito, P.Q., 2009. Shopping centre image dynamics of a new entrant. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 37(7), pp. 580-599.

- Brito, P.Q., McGoldrick, P.J. and Rau, U.R. Shopping Centre Patronage: Situational Factors Against Affect. Vision: the journal of Business Perspectives, 23(2), pp.189–196.

- Busitech., 2018. South African shopping centres will slowly start to ditch their massive parking garages. [online] Available at: https://businesstech.co.za/news/technology/239483/south-african-shopping-centres-will-slowly-start-to-ditch-their-massive-parking-garages [Accessed on 6 January 2023].

- Calvo-Porral, C. and Lévy-Mangin, J. P., 2019. Profiling shopping mall customers during hard times. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 48, pp. 238-246.

- Chebat, J.C., Sirgy, M.J. and Grzeskowiak, S., 2010. How can shopping mall management best capture mall image? Journal of Business Research, 63(7), pp. 735-740.

- Cvetković, M., Živković, J. and Lalović, K., 2018. Shopping centre as a leisure space: case study of Belgrade. 5th international academic conference – Places and Technologies, 26-27 April 2018.

- Dhiman, R., Chand, P.K., and Gupta, S., 2018. Behavioural aspects influencing decision to purchase apparels amongst young Indian consumers. FIIB Business Review, 7(3), pp. 188-200.

- Dubihlela, D. and Dubihlela, J., 2014. Attributes of shopping mall image, customer satisfaction and mall patronage for selected shopping malls in Southern Gauteng, South Africa. Journal of Economics and Behavioural Studies, 6(8), pp. 682-689.

- Duffet, R.G and Foster, C. 2018. The influence of shopping characteristics and socio-demographic factors on selected in-store buying practices in different socio-economic regions. Southern African Business Review, 22(91), pp.1-30.

- El-Adly, M.I. and Eid, R., 2015. Measuring the perceived value of malls in a non-Western context: the case of the UAE. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 43(9), pp. 849-869.

- El-Adly, M.I., 2007. Shopping malls’ attractiveness: a segmentation approach. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 35(11), pp. 936-950.

- Finn, A. and Louviere, J.J., 1996. Shopping centre image, consideration, and choice: anchor store contribution. Journal of Business Research, 35(3), pp.241-251.

- Frasquet, M., Gil, I. and Molla, A., 2001. Shopping-centre selection modeling: a segmentation approach. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 11(1), pp. 23-38.

- Frimpong, N.O., 2008. An evaluation of customers’ perception and usage of rural community banks (RCBs) in Ghana. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 3(2), pp. 181-196.

- Gomes. R.M. and Paula, F. 2017. Shopping mall image: systematic review of 40 years of research. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 27(1), pp. 1-27.

- Gudonaviciene, R. and Alijosiene, S., 2013. Influence of shopping centre image attributes on customer choices. Economics and Management, 18(3), pp.545-552.

- Gupta, A, Mishra, V. and Tandon, A. 2020. Assessment of Shopping Mall Customers’ Experience through Criteria of Attractiveness in Tier-II and Tier-III Cities of India: An Exploratory Study. American Business Review, 23(1), pp. 70-93. https://doi.org/10.37625/abr.

- Hasliza, H and Muhammad, M.S. 2012. Extended Shopping Experiences in Hypermarket. Asian Social Science; 8(11), pp 138-144.

- Hauser, J.R. and Koppelman, F.S. 1979. Alternative perceptual mapping techniques: relative accuracy and usefulness. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), pp.495-506.

- Hedhli, K.E. and Chebat, J.C., 2009. Developing and validating a shopper-based mall equity measure. Journal of Business Research, 62(6), pp. 581-587.

- Innovate, 2016. Exploring South Africa’s retail landscape. [online] Available at: https://www.coursehero.com/file/105569101/innovate-11-2016-exploring-sa-retail-landscapezp111498pdf/ [Accessed on 6 January 2023].

- Juhari, N.H., Ali, H.M. and Khair, N., 2012. The shopping mall servicescape affects customer satisfaction. 3rd International conference on business and economic research (3rd ICBER 2012) proceedings: March 2012. Golden Flower Hotel, Bandung, Indonesia.

- Kabadayi, S. and Paksoy, B., 2016. A segmentation of Turkish consumers based on their motives to visit shopping centres. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 26(4), 456-476. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2016.1157513.

- Khare, A., 2011. Mall shopping behaviour of Indian small town consumers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 18, pp. 110-118.

- Khei, M.W.G., Lu, Y. and Lan, Y.L., 2001. SCATTR: an instrument for measuring shopping centre attractiveness. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 29(2), pp. 76-86.

- Khurana, T. and Dwivedi, S., 2017. Customer satisfaction towards mall attributes in shopping malls of Udaipur. International Journal of Environment, Ecology, Family and Urban Studies (IJEEFUS), 7(2), pp. 25-28.

- Kursunluoglu, E.M., 2014. Shopping centre customer service: creating customer satisfaction and loyalty. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 32(4), pp. 528-548.

- Kushwaha, T., Ubeja, S. and Chatterjee, A.S., 2017. Factors influencing selection of shopping malls: an exploratory study of consumer perception. Vision 21(3), pp. 274-283.

- Kusumowidagdo, A., Sachari, A. and Widodo, P., 2014. Visitors’ perception towards public space in shopping center in the creation sense of place. 5th Arte Polis International Conference and Workshop – “Reflections on Creativity: Public Engagement and The Making of Place”, Arte-Polis 5, 8-9 August 2014, Bandung, Indonesia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 184, pp. 266-272.

- Lee, S.L., Ibrahim, M.F. and Hsueh-Shan, C., 2005. Shopping-centre attributes affecting male shopping behaviour. Journal of Retail and Leisure, 4(4), pp. 324-340.

- Levy, M., Weitz, B. and Pandit, A., 2012. Retail Management, 8th ed. New Delhi: McGraw Hill Education.

- Levy, M. and Weitz, B., 2004. Retailing Management. The McGraw-Hill Companies.

- Levy, M. and Weitz, B., 1998. Retailing Management, 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill, United States: New York, NY.

- Loudon, D.L. and Bitta, A.J.D., 1993. Consumer Behavior: Concepts and Applications, 4th ed. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

- Lovelock, C., Patterson, P. and Walker, R., 1998. Services Marketing: Australia and New Zealand. Prentice Hall: New South Wales, Australia.

- Mahin, M.A. and Adeinat, M.A., 2020. Factors driving customer satisfaction at shopping mall food courts. International Business Research, 13(3), 27-38.

- Mahlangu, E.N. and Makhitha, K.M., 2019. The impact of demographic factors on supermarket shopping motivations in South Africa. Journal of Business and Retail Management Research, 13(3), 11-25.

- Makhitha, K., 2014. The importance of supermarket attributes in supermarket choice among university students. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(23), 1751.

- Melkis, M., Hilmi, M.H. and Mustapha, Y., 2014. The influence of marital status and age on the perception of fast-food consumers in an emerging market. International Journal of Business and Innovation, 1(3), 33-43.

- Mihić, M. and Milaković, I.K., 2017. Examining shopping enjoyment: personal factors, word of mouth and moderating effects of demographics. Economic Research- Ekonomska Istraživanja, 30(1), 1300-1317.

- Nthle, D. 2023. The Social Dimension of Shopping Centres in South Africa Journal of Business and Management Review, 4(4), pp. 270-282.

- Okoro, D.P., Okolo, V.O. and Mmamel, Z.U., 2019. Determinants of shopping mall patronage among consumers in Enugu Metropolis. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9(11), 400-420.

- Olonade, O.Y., Busari, D.A., Idowu, B.O., David Imhonopi, D., George, T.O. and Adetund, C.A., 2021. Gender differences in lifestyles and perception of megamall patrons in Ibadan, Nigeria. Cogent Social Sciences, 7, 1-9.

- Ortegón-Cortázar, L. and Royo-Vela, M., 2017. Attraction factors of shopping centers. Effects of design and eco-natural environment on intention to visit. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 26(2), 199-219.

- Özkan, B., 2020. Evaluation of hedonic consumption habits of men in terms of demographic variables and horoscopes. Celal Bayar Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 18, pp.325-344.

- Pan, Y. and Zinkhan, G.M., 2006. Determinants of retail patronage: a meta-analytical perspective. Journal of Retailing, 82(3), pp.229-243.

- Park, S., 2016. What attracts you to shopping malls? The relationship between perceived shopping value and shopping orientation on purchase intention at shopping malls in suburban areas. In ‘Celebrating America’s Pastimes: Baseball, Hot Dogs, Apple Pie and Marketing’. Springer International, Denver, CO, pp 663–669.

- Parker, C.J. and Wenyu, L., 2019. What influences Chinese fashion retail? Shopping motivations, demographics and spending. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 23(2), pp. 158-175.

- Poovalingam, K. and Suleman Docrat, S., 2011. Consumer decision-making in the selection of shopping centres around Durban. Alternation, 18(1), pp.215-251.

- Rahmawati, R., 2019. Profiling shopping mall costumer based on demographics and shopping motivation. J-MKLI Jurnal Manajemen dan Kearifan Lokal Indonesia, 3(2), pp. 74-83.

- Rashmi, B.H., Poojary, H and Deepak, M.R. 2016. Factors Influencing Customer behaviour and its impact on Loyalty towards shopping malls of Bangalore City. IJEMR, 6(7), pp.1-14.

- Rousseau, G.G. and Venter, D.J.L., 2014. Mall shopping preferences and patronage of mature shoppers. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology/SA Tydskrif vir Bedryfsielkunde, 40(1), pp. 1-12.

- SACSC., 2020. Attracting shoppers back to malls post-lockdown. June. [online] Available at: https://sacsc.co.za/news/attracting-shoppers-back-to-malls-post-lockdown [Accessed on 14 December 2022].

- SACSC., 2017. Average shopping centre size on the rise. December. [online] Available at: https://sacsc.co.za/news/average-shopping-centre-size-on-the-rise#:~:text=Last%20year%2C%20Menlyn%20Park%20in%20Pretoria%2C%20now%20the,Fourways%20Mall%20expansion%20project%20in%20Johannesburg%20broke%20ground [Accessed on 13 December 2022]..

- Saprikis, V., Avlogiaris, G. and Katarachia. A., 2021. Determinants of the intention to adopt mobile augmented reality apps in shopping malls among university students. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res, 16, pp. 491-512.

- Singh, H. and Dash, P.C., 2012. Determinants of mall image in the Indian context: focus on environment. Asia-Pacific Journal of Management Research and Innovation, 8(4), pp. 407-415.

- Sit, J., Merrilees, B. and Birch, D. 2003. Entertainment‐seeking shopping centre patrons: the missing segments. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 31(2), pp. 80-94.

- Soomro, F., Kalwar, S., Memon, I.A. and Kalwar, A.B., 2021. Factor for boulevard shopping mall, Hyderabad City, Pakistan. International Research Journal of Innovations in Engineering and Technology (IRJIET), 5(10), pp. 19-22.

- Știr, M., 2018. Product Quality Evaluation in Physical Stores versus Online Stores. Expert Journal of Marketing, 6(1), pp. 7-13.

- Tongue, M.A., Otieno, R. and Cassidy, T.D., 2010. Evaluation of sizing provision among high street retailers and consumer buying practices of children’s clothing in the UK. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 14(3), 429-450.

- Tsai, S., 2010. Shopping mall management and entertainment experience: a cross-regional investigation. The Service Industries Journal, 30(3), pp. 321-337.

- Wong, S.C. and Nair, P.B., 2018. Mall patronage: dimensions of attractiveness in urban context. International Journal of Business and Society, 19(2), pp. 281-294.

- Wong, G.K.M., Lu, Y. and Yuan, L.L., 2001. SCATTR: an instrument for measuring shopping centre attractiveness. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 29(2), pp. 76-86.

- Wulandari, G.A., Suryaningsih, I.B. and Abriana, R.M. 2021. Co-shopper, mall environment, situational factors effects on shopping experience to encourage consumers shopping motivation. Journal of Applied Management (JAM), 19(3), pp. 547-560.

- Ying, H.C., Ng, A. and Aun, B., 2019. Examining factors influencing consumer choice of shopping mall: a case study of shopping mall in Klang Valley, Malaysia. BERJAYA Journal of Services and Management, 11, pp. 82-102.

Article Rights and License

© 2023 The Author. Published by Sprint Investify. ISSN 2359-7712. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.