Keywordsbrand identity Brand Personality content analysis corporate branding higher education

JEL Classification M30, M31

Full Article

1. Introduction

Marketing is no longer about the products or services that one sells, but about the personal touch that a company puts forth in communicating with their target audience. Digital transformation, opened the pathway for businesses to communicate, approach, react, and deliver services to customers in a personalised and unique manner (He et al., 2023). The Higher education (HE) landscape is also affected by this transformation, and this amplifies the need for distinctiveness (Zapp et al., 2021). HE institutions across the globe are operating in a highly competitive industry faced with intense challenges (Natalia & Ellita, 2019). Furthermore, HE is a complex system that requires multiple levels of analysis to understand the dynamics, context, and actions concerning technological innovations (Castro, 2019). To deal with these challenges and transformation within the educational landscape, higher education institutions (HEIs) are increasingly adopting marketing and branding strategies that are typically associated with the for-profit sector (Balaji et al., 2016; Clark et al., 2020; Kaushal and Ali, 2020; Lim et al., 2020; Tien et al., 2019). HEIS must develop and implement sound strategies to differentiate themselves in the minds of their students as well as other stakeholders. This paper focuses specifically on how brand personality (BP) is applied as a positioning strategy for seven specific types of HEIs in an emerging country context.

BP is the human traits or characteristics that the brand holds if it were to come alive as a person (Mao et al., 2020). The personality of a brand is thus the way a company portrays itself to the market. Brand differentiation and image creation are key considerations in the strategy of any organisation (Ramesh et al., 2019). The strategic plans of universities thus play an important role, not only in guiding an organisation's decisions and actions toward success but also in revealing their planned BP and identity (Naheen and Elsharnouby, 2021).

Systematic reviews of the evolution of BP themes published over the past two decades showed that the initial focus was on consumer brands, whereafter it shifted to include corporate brands (e.g. Anaya-Sánchez and Ekinci, 2023; Calderón-Fajardo et al., 2020). The potential role that the personality of a brand can play in HEI positioning has largely been neglected until the 21st century. Academic studies on the potential of BP for HE slowly started to surface over the past two decades, but the need for more research into this matter is crucial (Kaushal and Ali, 2020; Opoku, et al., 2006). Some researchers conducted surveys to determine students’ perceptions regarding the BP of universities in India (Kaushal and Ali, 2020), Malaysia (Balaji, et al., 2016), Germany, North America (Rauschnabel et al., 2016), the USA, Egypt (Mourad et al., 2020) and in Kenia (Simiyu et al., 2020). These studies offered valuable insight into students’ perspectives of HEIs’ BP. They however did not consider how the brand qualities are planned as part of a strategy aimed at influencing their internal and external stakeholders. Other scholars applied content analysis to determine how university BP is reflected in traditional media (e.g. Rutter et al., 2017) and digital media (e.g. Frank et al., 2020; Opoku et al., 2006). These scholars however have not examined BP specifically in the strategic or marketing plans of HEIs). There is thus an opportunity to leverage the analytical approaches embraced in the study of BP in Higher education, and to understand the role BP plays in the positioning of HEIs. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to conduct a lexical analysis of HEIs’ strategic plans, in order to determine how the BP dimensions are being applied at all the Universities of Technologies (UoTs) in South Africa.

Literature on HE and the role that BP plays in it is discussed next. Then, the methods and results of the study are considered. Lastly, the article offers implications, limitations, directions for future research, and conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Higher Education Institutions and Branding

Organisations within the educational sector are classified as mass service providers, based on the low level of customisation and high levels of participation (Kang, 2021). In higher education, a wide variety of general qualifications and programs are offered that cannot be customised to the individual needs of each student. However, upon acceptance, the learner participates actively in the teaching and learning activities, provided by the university (Raza et al., 2020).

Within South Africa, the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) oversees the functions, planning and development of sustainable universities within the country (Heleta, 2022). Three types of universities are found within the HE sectors namely, traditional universities, Universities of Technology (UoT) and comprehensive universities (Department of Higher Education and Training, 2023). Traditional universities are known to offer theoretical-oriented qualifications whereas UoTs offer vocational-oriented diplomas and degrees. Comprehensive universities, on the other hand, offer both theoretical and vocational qualifications (Department of Higher Education and Training, 2023).

The functions of UoTs in South Africa are unique in the sense that these universities are duly concerned about the human resource needs within the country (Mtotywa et al., 2023). Additionally, these universities prepare learners to practically apply theory and technology within the work situation. The UoTs also work closely in collaboration with industry, to ensure that the curriculum is in line with industry needs (Bouwer, 2020). Quality within HE is becoming critical seeing that global competitiveness, managerialism, and internalisation are shaping the institutional ranking and rating of the institution (Antoniuk, 2019; Ntshoe and Letseka, 2010). Globally, universities are starting to promote their key priorities by focusing on their best practices which ultimately create and attractive teaching and learning environment for students (Antoniuk et al., 2019).

The use of marketing strategies within HE is like those used within other industries; since the elements and use of the brand are generally similar (De Wit and Altbach, 2021). The brand of a company assists in the facilitation of communication efforts by informing the target market of any new product or service offering, which could ultimately lead to repeat purchases and loyalty (Lim, 2023). The increase of competitors within the educational space necessitates the need for differentiation through branding (Ogunmokun et al., 2021). The brand of an organisation can influence the perceptions of the target market and when it comes to HEIs, how a university portrays itself can influence the decision-making process of students (Rutter et al., 2017).

2.2. Corporate Branding and Identity

During the previous century, cattle ranchers used to brand their cattle to distinguish their animals from those of their neighbours. Big companies followed the same principle by adding recognisable labels to their products, to differentiate them (Lloyd, 2019). Since 1880, corporate branding evolved to such an extent that nowadays, all companies are using some form of identification to present their brands and various product offerings across many different sectors (LaMarco, 2019). A corporate brand is generally rich in tradition and heritage; has a high level of capability and or assets; has a local and international presence; is influential; has values and excellent performance records (Nukhu, and Singh 2020). On the other hand, corporate identity is defined as how an organisation views and portrays itself to the public (Melewar et al., 2021). The word, colour schemes, trademarks, and designs all form part of building the corporate identity of a company (Melewar et al., 2021).

Brand identity and corporate identity are related concepts, and both play a crucial role in how organisations present themselves to the public to establish a unique image (Balmer and Podnar, 2021). Corporate identity and branding are based on the mission, vision, and direction of an organisation and provide a strategic focus for positioning stakeholders in a personalized manner (Goncharova et al., 2019).

A brand can be defined as a term, name, symbol, design, or any other feature that distinguishes one good or service from another (Tien et al., 2021). Corporate identity entails how an organisation views itself and how it portrays itself to the public (Balmer et al., 2021). Brand identity is created using features such as words, colour schemes, trademarks, and the design of a brand to build the corporate identity of the company (Alvarado-Karste and Guzmán, 2020). Corporate identity is thus the overall image and behaviour of the entire company.

2.3. Brand Personality

Personality from a psychological perspective, entails the individual differences and traits between people, and the way they feel, think and behave (Bergner, 2020). BP is defined as “the set of human characteristics associated with the brand” (Aaker 1997). The personality of a brand emerges once the mission, vision and purpose of the brand are uncovered and defined (Tien et al., 2021). BP is thus a mechanism that organisations, including universities, can use to create awareness of and loyalty towards the brand within the minds of the consumers (Bastug et al., 2020). The set of human characteristics assigned to the brand, are developed in line with the strategic objectives of the organisation to which consumers can relate (Traver, 2020).

Over the years, research found that consumers can easily assign human characteristics to products or brands, to personify and build a relationship with the brand (Braxton et al., 2020). Selecting a brand with personality characteristics that the consumer can identify with, can assist with the development of a visible presentation of the consumer’s ideal self (Liu et al., 2020). A well-established brand with a strong unique personality in the mind of consumers increases preference and usage of the product and/or a service and ultimately increases loyalty (Gilovich and Gallo, 2020; Yang et al., 2020).

The use of BP within HEIs can assist with the differentiation and competitiveness that enable students to relate and identify themselves with the university’s brand (Balaji et al., 2016). Jennifer Aaker (1997) introduced the concept of BP, and scholarly studies into BP have since become widespread (Batra, 2019). Aaker developed the BP scale based on the human dimensions of personality that comprise excitement, sincerity, competence, ruggedness, and sophistication (Hompes, 2021). Over the years various scholars applied the BP as per Aaker’s model to education and some even adapted it. A summary of the studies is depicted in Table 1.

Table 1. Prior research on the use of Brand Personality in HEIs

|

Source Research aim |

Methods/Material and Context | Findings |

|

Kaushal, and Ali, 2020 The mediating role of BP components and how it translates into loyalty |

Questionnaires A large university in India |

BP has a great impact on loyalty toward the university. Prestige, appeal, sincerity, cosmopolitan, lively and conscientiousness were identified as visible BP dimensions. |

|

Balaji et al., 2016 The role of university BP, knowledge, prestige in student-university identification |

Self- administrated questionnaires University in Malaysia | Br& knowledge and br& prestige of the university play an important role in determining student identification. By being able to personally identify with the university drives the desire of the students to engage in university supportive behaviours. |

|

Mourad, et al., 2020 The influence of BP on equity at HEIs |

Mixed Research Methodology: questionnaires and focus group in U.S.A and Egypt |

BP and social image are important however they vary depending on the maturity of the HEIs as well as the cultural context. |

|

Simiyu, et al., 2020 The effect of attitude on the relationship between social media and BP in HE |

Self-administrated questionnaires Students in Kenya | BP has a mediating effect on the relationship between social media and the intentions to enroll in studies at the university. The higher the BP elements the higher the behaviour intentions to enroll. |

|

Rauschnabel, et al., 2016 To develop a theoretically based measurement model to assess BP in HE. |

A mixed-method study Germany and the U.S.A. |

The prestige/performance personality factor was ranked amongst the top and it represents the university's overall reputation. This was followed by sincerity and lively as personality dimensions. |

|

Rutter et al., 2017 The relative positions of BP dimensions |

Quantitative content analysis and multiple correspondence analysis of prospectuses. Top U.K universities |

A clear differentiation between the various universities was found, however, excitement and competence were present for all universities. The top universities are high in terms of Sophistication and Competence but lower in terms of Excitement and Ruggedness. |

|

Opoku et al., 2006 The BP dimensions portrayed by Business Schools |

Content analysis of websites of South African Business Schools | Competence and sincerity were the most visible dimensions. |

|

Frank, et al., 2020 The BP of business schools |

Content analysis of the business school’s website The U.S.A. |

Public universities highlighted competence more, while private universities focused on excitement and sincerity. Those with higher enrolment numbers portray themselves as more competent while those with lower enrolments view themselves as sincere. |

Source: Own compilation

When considering these findings, it is clear that the use of BP in HE is evolving and successfully used by different HEIs to create a strong and unique brand presence in competing environments. Furthermore, these HEIS across the globe mostly rely and build predominantly on the Performance (Competence), Leading (Sophistication) Credibility (Sincerity) BP dimensions as strategic differentiators, while Exciting (Excitement) and Resilience (Ruggedness) are less prominent. However, more in-depth research on the use of BP by HEIs in other developing countries such as South Africa is needed (Mourad et al., 2020; Opoku et al., 2006).

3. Research Methodology

The purpose of this research is to examine the BP dimensions projected within the strategic plans of UoTs. Strategic plans not only describe these institutions’ mission, goals, and strategic plans (Flores and Leal, 2023) but also reveal their planned BP and identity (Naheen and Elsharnouby, 2021; Jain et al., 2014). A content analysis was applied as research method, to analyze the data for this study. Researchers can analyze and quantify the presence of certain concepts, words or themes when conducting a content analysis (Manthiou, Klaus and Luong, 2022). The data analysis tool, Atlas.ti, was used to calculate the frequencies of the BP elements that appear within the strategic plans of the selected universities. Thereafter, the data were grouped according to the specific dimensions of BP.

3.1. Sample

Through Judgement sampling, UoTs were selected as sample units in this study because the program offerings of these UoTs are similar and therefore the need to differentiate themselves through their BP. Judgement sampling is a non-probability sampling technique, in which sample units are selected based on the researcher's own experience, judgement and knowledge (Adeoye, 2023). These HEIs regularly experiment with new practices and approaches to deliver and design new teaching and learning initiatives (Council of Higher Education, 2010).

Table 2. Universities of Technology in South Africa

| Sample: Universities of Technology |

| Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT) |

| Central University of Technology (CUT) |

| Durban University of Technology (DUT) |

| Mangosuthu University of Technology (MUT) |

| Tshwane University of Technology (TUT) |

| Vaal University of Technology (VUT) |

| Walter Sisulu University of Technology and Science (WSU) |

The strategic plans are used by both internal and external stakeholders to understand and evaluate the mission, vision, strategic goals, and objectives of the university (Morphew and Hartley, 2006). The strategic plans of the selected UoTs were obtained and downloaded from the respective websites of the universities. These documents were then uploaded into the statistical software program Atlas.ti for analysis.

3.2. Data Analysis and Measurement

Content analysis entails the analyses of images, text and significant sources to make valid conclusions, to the context of their usage (Roller, 2019). Content analysis is a well-accepted method in marketing and has been widely applied to analyse commercial companies’ brand communication on different advertising and media platforms (Belch and Belch, 2013; Greer and Ferguson, 2011; Shen and Bissell, 2013; Vázquez-Herrero, et al., 2022). It has also been applied within the educational environment to analyse institutions' representation and communication in traditional media, and online media (Frank, et al., 2020, Kahan and McKenzie, 2020; Opoku et al., 2006; Rutter et al., 2017). In this study it has been applied to examine BP dimensions in the strategic plans of HEIs.

The assessment of the textual data in a quantifiable manner for this study was managed with content analysis. To analyse the text in the strategic plans of HEIs, a BP dictionary (see Table 3) was developed and refined by the researchers informed by the scale of Opoku et al. (2006). Five BP dimensions were included namely i) Performance which emphasises the functional brand associations relevant to HEIs such as professionalism and science. ii) Leading which emphasises the brand's role as a pioneer and trendsetter iii) Credibility relating to a brand’s trustworthiness and helpfulness to form emotional relationships and minimize perceived risk. Iv) Exciting which highlights the visionary aspects such as opportunities and transformation v) Resilience signifies the durability and adaptability to thrive in demanding environments. The dimensions dictionary comprised of broad terms and higher education-specific terms, to reflect the context of the industry. This is aligned with the practices of other studies which apply adjusted BP dimensions to suit the context of the industry (Frank, et al., 2020; Kaushal and Ali, 2020; Mourad et al., 2020; Opoku et al., 2006; Rauschnabel, et al., 2016). Examples of the frequently found words within the strategic documents related to each of the brand dimensions are tabled below.

Table 3. Higher Education Brand Personality Dictionary

| BP Dimensions | Broad terms | Higher Education specific terms |

|

Performance (Competence) |

Global, international, impactful, best, excellent, successful, dynamic | Academic, Professional, science intellectual, research, intelligence analysis, business-driven, employability |

|

Leading (Sophistication) |

Leadership, quality, excellence, success, innovative, impactful, leading, progress, lead, best, cutting edge, excellent, positioning, reputation | Research, technology, smart innovation, science, international economic partnerships, technology, industry practice |

|

Credibility (Sincerity) |

Understanding, ethical, integrity, embracing, safe, caring, trust, encourage, friendly, fair, trust, tolerance | Transparency, community engagement, society, humane, cultural, wellness, mutual, equality, collegiality |

|

Exciting (Excitement) |

Readiness, creativity, play, energy, potential, living, life, freedom, play, reimagining | Vision, future, opportunities, transformation, initiatives, diverse, revolution |

|

Resilience (Ruggedness) |

Work, enhance, strengthen, strong, resilient, actively, strong, act | Practical, independent, operate, agile, robust, business, baseline, sustainable, employable |

Source: Own compilation

Using content analysis, the textual data BP words within the strategic plans) were counted. Table 4 below shows the word counts within the strategic plans for each UoT. The seven strategic plans provided a total of 36982 words (excluding numbering, single character words, hyphens, and underscores), and for analysis.

Table 4. Total number of words per the strategic plan

| Name of University of Technology | Total number of words |

| Cape Peninsula University of Technology | 6635 |

| Central University of Technology | 9378 |

| Durban University of Technology | 2438 |

| Mangosuthu University of Technology | 5152 |

| Tshwane University of Technology | 1277 |

| Vaal University of Technology | 5076 |

| Walter Sisulu University of Technology and Science | 7025 |

To determine whether the UoTs used distinct BP words in their strategic plans, the researchers applied content analysis. Word count and word percentage for each of the five BP dimensions were determined. After the analysis of the strategic plans, the collected data were examined, to identify patterns and to draw conclusions in response to the research question.

4. Results

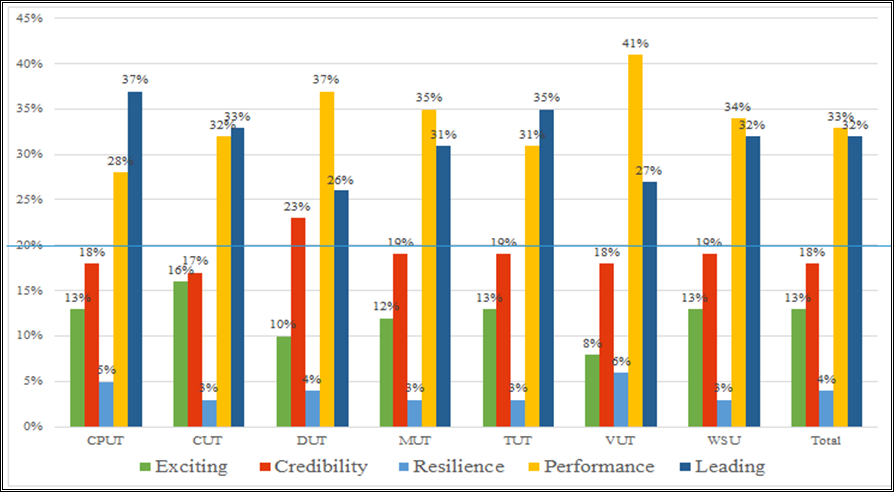

When comparing the relative focus per BP dimension across all the UoTs analysed, the distributions between the five dimensions are relatively similar (see Figure 1). This implies that these institutions must be careful not to develop and implement strategies that are so similar that they do succeed in differentiating themselves in the minds of their stakeholders.

Figure 1. The brand personality dimensions of South African Universities of Technologies

Source: Own compilation

When comparing the word percentage by BP dimension the focus is mostly on the performance- (33%) and leading dimensions (32%) as strategic differentiators. The emphasis on performance is like other studies on the BP portrayed in the media of top business schools in South Africa (Opoku et al., 2006) as well as globally (Frank et al., 2020; Rutter et al., 2017). The attention paid to leading (32%) can be explained considering that leadership within HE is crucial in providing excellence, justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion within a university (Russell et al., 2021). Being a pioneer also relates to the use of digital technologies within teaching and learning to provide complementary insights that can align leading and learning goals (Castro, 2019). The relatively high emphasis placed on credibility (18%) in this study is aligned with the focus of top business schools on trustworthiness in South Africa (Opoku et al., 2006) and smaller institutions in the USA positioning them as sincere to attract students (Frank et al., 2020).

The exciting (13%) and resilience (4%) dimensions were found to receive limited attention in the strategic plans of the selected UoTs. The findings collate with those of Opoku et al., 2006) who found that ruggedness was amongst the least visible dimensions used within HEIs in South Africa.

Table 5. The brand personality dimensions of South African Universities of Technologies

| Institutions | ||||||||

| BP dimensions | CPUT | CUT | DUT | MUT | TUT | VUT | WSU | Total |

| Exciting | ||||||||

| Word count | 278 | 338 | 71 | 178 | 40 | 106 | 211 | 1222 |

| Percentage | 13% | 16% | 10% | 12% | 13% | 8% | 13% | 13% |

| Credibility | ||||||||

| Word count | 392 | 358 | 155 | 277 | 58 | 234 | 309 | 1783 |

| Percentage | 18% | 17% | 23% | 19% | 19% | 18% | 19% | 18% |

| Resilience | ||||||||

| Word count | 101 | 66 | 25 | 42 | 10 | 73 | 48 | 365 |

| Percentage | 5% | 3% | 4% | 3% | 3% | 6% | 3% | 4% |

| Performance | ||||||||

| Word count | 613 | 677 | 251 | 499 | 97 | 543 | 570 | 3250 |

| Percentage | 28% | 32% | 37% | 35% | 31% | 41% | 34% | 33% |

| Leading | ||||||||

| Word count | 814 | 702 | 179 | 448 | 108 | 356 | 528 | 3135 |

| Percentage | 37% | 33% | 26% | 31% | 35% | 27% | 32% | 32% |

| Total | 2198 | 2141 | 681 | 1444 | 313 | 1312 | 1666 | 9755 |

| 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

5. Discussion and Conclusion

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

Informed by previous studies that explored the use of BP within HE, this study aimed to examine the BP dimensions projected within the strategic plans of universities in South Africa. The aim was achieved by examining the content of the strategic plans of seven Universities of Technology within South Africa. Aaker (1997) identified excitement, sincerity, competence, ruggedness, and sophistication as BP dimensions while Opoku et al. (2006) adapted it for education to exiting, credibility, resilience, performance, and leading.

This paper is one of the first to conduct a lexical analysis of HEIs’ strategic plans to analyze the BP dimensions. A novel Higher Education Brand Personality Dictionary was developed to be used by other marketing scholars and practitioners.

5.2. Managerial Implications

Despite UoT each having its own set of values, requirements, norms, beliefs, and target markets, the results revealed little differences in terms of BP dimensions within their strategic plans, hence the need for differentiation. The target markets and stakeholders of the UoTs are different because the UoTs are located within different provinces in South Africa each with unique challenges and opportunities. Objective SWOT analysis and further research to understand the needs and perceptions of their target markets and unique contexts are advised to assist with BP customization and personalization in the strategic plan.

Overall performance and leading dimensions were planned to be used as key strategic differentiators, but resilience seem to be ignored. Focusing on the ability of the university to adapt and identify potential opportunities inside and outside the university as well as how the university identifies potential threats and critical issues can enhance resilience. Additionally, making stakeholders aware of how the university acts during risky and challenging times can also contribute to this dimension.

The success of a corporate-brand strategy is linked to the brand-personality traits that can give universities a competitive edge and the lack thereof opens room for competitors within the market space. Leadership, innovation, and student-centeredness alone are not sufficient to create and maintain a strong and unique brand presence. Universities therefore need to establish strong collaborations and partnerships that could assist in closing the gap between the university and the community at large to become more identifiable with the brand. The use of the adapted brand-personality model for HE can benefit universities such as UoTs in communicating effectively with their target audience.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions of Research

Understanding the role and influence of BP on the target market could assist the management of universities with the necessary knowledge to create strategies that all stakeholders can identify and relate with. By doing so, loyalty and trust towards the brand can be established seeing that those involved would feel a sense of belonging which they identify with. Some limitations were identified and should be mentioned. Firstly, only the strategic plans of Universities of Technologies in South Africa were analyzed thus excluding the traditional universities. Secondly, this study only considered the actual strategic plans of the universities and did not measure the perceptions of the students or any other stakeholders regarding how they perceive the use of brand personality by the university. With that said, in order to understand the application of BP within HEI, more research is needed to compare how the strategic plans of UoTs differ from traditional universities in South Africa. Additionally, international comparisons are also needed since HEIs no longer only compete locally. Furthermore, by measuring the perceptions of students and other stakeholders can provide more in-depth knowledge on how HEI’s can adapt the current use of brand personality in order to be more aligned with their target market. A well-designed strategic plan is a must-have in today’s competitive environment and must not be overlooked or overtaken by irrelevant terms that are not customer-focused. One must always remember that “Your brand is what other people say about you when you’re not in the room” – Jeff Bezos.

---

Author Contributions: Author1: Conceptualization and theoretical framework, Writing of the draft article, Editing, Data Collection and Validation. Author 2: Research Methodology, Data Analysis, Visualization, Validation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aaker, J., 1997. Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 34(3), pp.347-356, doi:10.1177/002224379703400304.

- Adeoye, M.A., 2023. Review of Sampling Techniques for Education. ASEAN Journal for Science Education, 2(2), pp.87-94.

- Alvarado-Karste, D. and Guzmán, F., 2020. The effect of brand identity-cognitive style fit and social influence on consumer-based brand equity. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 29(7), pp.971-984.

- Antoniuk, L., Kalenyuk, I., Tsyrkun, O. and Sandul, M., 2019. Rankings in the higher education competitiveness management system. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 17(4), p.325.

- Balaji, M.S., Roy, S.K. and Sadeque, S., 2016. Antecedents and consequences of university brand identification. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), pp.3023-3032.

- Balmer, J.M. and Podnar, K., 2021. Corporate brand orientation: Identity, internal images, and corporate identification matters. Journal of Business Research, 134, pp.729-737.

- Baştuğ, S., Şakar, G.D. and Gülmez, S., 2020. An application of brand personality dimensions to container ports: A place branding perspective. Journal of Transport Geography, 82, p.102552.

- Belch, G. E. and Belch, M.A., (2013). A Content Analysis Study of The Use of Celebrity Endorsers In Magazine Advertising. International Journal of Advertising, 32(3), pp. 369– 389. doi:10.2501/IJA-32-3-369-389

- Bergner, R.M., 2020. What is personality? Two myths and a definition. New Ideas in Psychology, 57, p.100759.

- Bouwer, R., 2020. UoT’s and strategic transformation of educational programs: Where and how should UoT’s connect. Available at:https://www.cput.ac.za/images/Faculties/Business/HEQF/UOTs%20and%20strategic%20transformation%20of%20educational%20programmes.pdf. [Accessed: 14 July 2023].

- Braxton, D. and Lau-Gesk, L., 2020. The impact of collective brand personification on happiness and brand loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 54(10), pp.2365-2386.

- Calderon-Fajardo, V., Molinillo, S., Anaya-Sánchez, R. and Ekinci, Y., 2023. Brand personality: Current insights and future research directions. Journal of Business Research, 166, p.114062.

- Castro, R., 2019. Blended learning in higher education: Trends and capabilities. Education and Information Technologies, 24(4), pp.2523-2546.

- Clark, P., Chapleo, C. and Suomi, K., 2020. Branding higher education: an exploration of the role of internal branding on middle management in a university rebrand. Tertiary Education and Management, 26, pp.131-149.

- Coelho, F.J., Bairrada, C.M. and de Matos Coelho, A.F., 2020. Functional brand qualities and perceived value: The mediating role of brand experience and brand personality. Psychology & Marketing, 37(1), pp.41-55.

- Council of Higher Education., 2023. Universities of Technology: Deepening the debate. Kagisano No 7.

- Crimmins, G. ed., 2022. Strategies for supporting inclusion and diversity in the academy: Higher education, aspiration and inequality. Springer Nature.

- Department of Higher Education and Training., 2023.Together moving post school together. [online] Available at: https://www.dhet.gov.za/SitePages/UniversitiesinSA.aspx. [Accessed 16 July 2023].

- De Wit, H. and Altbach, P.G., 2021. Internationalization in higher education: Global trends and recommendations for its future. In Higher Education in the Next Decade (pp. 303-325). Brill

- Flores, A. and Leal, D.R., 2023. Beyond enrollment and graduation: Examining strategic plans from Hispanic-serving institutions in Texas. Journal of Latinos and Education, 22(2), pp.454-469.

- Frank, B., Beldona, S. and Wysong, S., 2020. Website words matter: an analysis of business schools' online brand personalities. Journal for Global Business Advancement, 13(1), pp.53-69.

- Gilovich, T. and Gallo, I., 2020. Consumers’ pursuit of material and experiential purchases: A review. Consumer Psychology Review, 3(1), pp.20-33.

- Goncharova, N.A., Solosichenko, T.Z. and Merzlyakova, N.V., 2019. Brand platform as an element of a company marketing strategy. International Journal of Supply Chain Management, 8(4), p.815.

- Greer, C.F. and Ferguson, D.A., 2011. Using Twitter for promotion and branding: A content analysis of local television Twitter sites. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 55(2), pp.198-214.

- He, Z., Huang, H., Choi, H. and Bilgihan, A., 2023. Building organizational resilience with digital transformation. Journal of Service Management, 34(1), pp.147-171.

- Heleta, S., 2022. Critical review of the policy framework for internationalisation of higher education in South Africa. Journal of Studies in International Education, p.102.

- Hompes, J., 2021. Co-creation in brand development between Europe and China: Creating a tool using Artificial Intelligence to improve collaboration.

- Kahan, D. and McKenzie, T.L., 2020. School websites: A physical education and physical activity content analysis. Journal of School Health, 90(1), pp.47-55.

- Kang, B., 2021. How the COVID-19 pandemic is reshaping the education service. The Future of Service Post-COVID-19 Pandemic, Volume 1: Rapid Adoption of Digital Service Technology, pp.15-36.

- Kaushal, V. and Ali, N., 2020. University reputation, brand attachment and brand personality as antecedents of student loyalty: A study in higher education context. Corporate Reputation Review, 23, pp.254-266

- LaMarco, N., 2019. Corporate Branding vs. Product Branding. https://smallbusiness.chron.com/ corporate-branding-vs-product-branding-37269.html

- Lloyd, T., 2019. Defining What a Brand Is: Why Is It So Hard? [online] Available at: https://www.emotivebrand.com/defining-brand/

- Lim, W.M., Jee, T.W. and De Run, E.C., 2020. Strategic brand management for higher education institutions with graduate degree programs: empirical insights from the higher education marketing mix. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 28(3), pp.225-245.

- Lim, W.M., 2023. Transformative marketing in the new normal: A novel practice-scholarly integrative review of business-to-business marketing mix challenges, opportunities, and solutions. Journal of Business Research, 160, p.113638.

- Liu, C., Zhang, Y. and Zhang, J., 2020. The impact of self-congruity and virtual interactivity on online celebrity brand equity and fans’ purchase intention. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 29(6), pp.783-801.

- Manthiou, A., Klaus, P. and Luong, V.H., 2022. Slow tourism: Conceptualization and interpretation–A travel vloggers’ perspective. Tourism Management, 93, p.104570.

- Mao, Y., Lai, Y., Luo, Y., Liu, S., Du, Y., Zhou, J., Ma, J., Bonaiuto, F. and Bonaiuto, M., 2020. Apple or Huawei: Understanding flow, brand image, brand identity, brand personality and purchase intention of smartphone. Sustainability, 12(8), p.3391

- Melewar, T.C., Dennis, C. and Foroudi, P. eds., 2021. Building corporate identity, image and reputation in the digital era. Routledge.

- Morphew, C.C. and Hartley, M., 2006. Mission statements: A thematic analysis of rhetoric across institutional type. The Journal of Higher Education, 77(3), pp.456-471.

- Mourad, M., Meshreki, H. and Sarofim, S., 2020. Brand equity in higher education: comparative analysis. Studies in Higher Education, 45(1), pp.209-231.

- Mpungose, C.B., 2020. Are Social Media Sites a Platform for Formal or Informal Learning? Students' Experiences in Institutions of Higher Education. International Journal of Higher Education, 9(5), pp.300-311.

- Mtotywa, M.M., Seabi, M.A., Manqele, T.J., Ngwenya, S.P. and Moetsi, M., 2023. Critical factors for restructuring the education system during the era of the fourth industrial revolution in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, pp.1-22.

- Naheen, F. and Elsharnouby, T.H., 2021. You are what you communicate: on the relationships among university brand personality, identification, student participation, and citizenship behaviour. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, pp.1-22.

- Natalia, I. and Ellitan, L., 2019. Strategies to Achieve Competitive Advantage In Industrial Revolution 4.0. International Journal of Research Culture Society, 3(6), pp.10-16.

- Ntshoe, I. and Letseka, M., 2010. Quality assurance and global competitiveness in higher education. In Higher education, policy, and the global competition phenomenon (pp. 59-71). New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Nukhu, R. and Singh, S., 2020. Branding dilemma: the case of branding Hyderabad city. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 6(3), pp.545-564.

- Ogunmokun, O.A., Unverdi-Creig, G.I., Said, H., Avci, T. and Eluwole, K.K., 2021. Consumer well‐being through engagement and innovation in higher education: A conceptual model and research propositions. Journal of Public Affairs, 21(1), p.e2100.

- Opoku, R., Abratt, R. and Pitt, L., 2006. Communicating brand personality: are the websites doing the talking for the top South African business schools? Journal of Brand Management, 14(1-2), 20-39.

- Ramesh, K., Saha, R., Goswami, S., Sekar and Dahiya, R., 2019. Consumer's response to CSR activities: Mediating role of brand image and brand attitude. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(2), pp.377-387.

- Rauschnabel, P. A., Krey, N., Babin, B. J. and Ivens, B. S., 2016. Brand management in higher education: The university brand personality scale. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3077–3086. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.01.023

- Raza, S.A., Qazi, W. and Umer, B., 2020. Examining the impact of case-based learning on student engagement, learning motivation and learning performance among university students. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 12(3), pp.517-533.

- Roller, M.R., 2019, September. A quality approach to qualitative content analysis: Similarities and differences compared to other qualitative methods. In Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(3).

- Russell, J.A., Gonzales, L.D. and Barkhoff, H., 2021. Demonstrating equitable and inclusive crisis leadership in higher education. Kinesiology Review, 10(4), pp.383-389.

- Rutter, R., Lettice, F. and Nadeau, J., 2017. Brand personality in higher education: anthropomorphized university marketing communications. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 27(1), pp.19-39.

- Shen, B. and Bissell, K., 2013. Social media, social me: A content analysis of beauty companies’ use of Facebook in marketing and branding. Journal of Promotion Management, 19(5), pp.629-651

- Simiyu, G., Bonuke, R. and Komen, J., 2020. Social media and students’ behavioral intentions to enroll in postgraduate studies in Kenya: a moderated mediation model of brand personality and attitude. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 30(1), pp.66-86.

- Tien, N.H., Anh, D.B.H., Ngoc, P.B., Trang, T.T.T. and Minh, H.T.T., 2021. Brand Building and Development for the Group of Asian International Education in Vietnam. Psychology and education, 58(5), pp.3297-3307.

- Tien, N.H., Minh, H.T.T. and Dan, P.V., 2019. Branding building for Vietnam higher education industry-reality and solutions. International Journal of Research in Marketing Management and Sales, 1(2), pp.118-123.

- Traver, E., 2020. Brand Personality. [online] Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/brand-personality.asp#:~:text=Brand%20personality%20is%20a%20set,a%20specific%20consumer%

- Vázquez-Herrero, J., Negreira-Rey, M.C. and López-García, X., 2022. Let’s dance the news! How the news media are adapting to the logic of TikTok. Journalism, 23(8), pp.1717-1735.

- Veles, N. and Danaher, P.A., 2022. Transformative research collaboration as third space and creative understanding: learnings from higher education research and doctoral supervision. Research Papers in Education, pp.1-17.

- Yang, L.W., Aggarwal, P. and McGill, A.L., 2020. The 3 C's of anthropomorphism: Connection, comprehension, and competition. Consumer Psychology Review, 3(1), pp.3-19.

- Zapp, M., Marques, M. and Powell, J.J., 2021. Blurring the boundaries. University actorhood and institutional change in global higher education. Comparative Education, 57(4), pp.538-559.

Article Rights and License

© 2023 The Authors. Published by Sprint Investify. ISSN 2359-7712. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.