Keywordscustomer service independent food chains purchasing patterns Retailing

JEL Classification M31

This paper has previously been included in an open access repository as a Doctoral Thesis

Full Article

1. Introduction

The history and the development of the food chains in South Africa are not only very interesting but also speak of a dynamic and growing sector which is a highly competitive and challenging industry which is also experiencing significant changes and challenges (Huddleston et al., 2009, p.63). Food chains started in South Africa around 1951 when OK Bazaars opened a food department store as its flagship store. Since then, many entrants have followed into the industry. It is perceived that some food chains started quite early, but have expanded significantly only recently.

Food retailing has also evolved from being a buying ritual to delivering a joyful shopping experience. Food retailers are now integrating a series of services and events leading to a pleasurable, involving, relaxing, rewarding, delightful retail customer experience (Bagdare and Jain, 2013, p.790), and to manage a customer’s experience, retailers should understand what customer service means (Grewal et al., 2009, p.1).

In today’s competitive retail environment many independent retail food chains need to develop strategies to compete (Mower et al., 2012, p.443), as the current market place has become more competitive and customers are continually expecting retailers to match or exceed their expectations (Beneke et al., 2012, p.28). There is a misconception by independent retail food chains that the only way to remain competitive is to focus on price since many customers will only buy the cheapest products (Chiliya, Herbst and Roberts-Lombard, 2009, p.72). However, several other factors also play a central role in customer decision-making which include customer service, addressing the needs of customers, as well as timely delivery on promises (Du Plooy et al., 2012, p.94).

Post-apartheid, the South African independent retail food chain industry has rapidly increased in size and stature, yet customer service does not appear to have kept pace with growth (Beneke et al., 2012, p.27). The independent retail food chains have positioned themselves for all kinds of customer needs and income levels; it is, however, not clear whether these retailers have fully embraced the retail concept which emphasis on proper communication, total retail experience, customer service, relationship retailing and consistent retail strategy (Kimani et al., 2012, p.55). This study aims to determine and evaluate customer service undertaken by independent food chains in KwaZulu-Natal and the applicability of any strategies thereof.

2. Literature Review

Customer service refers to the combination of activities offered by retailers. If taken seriously, Customer Service is presented to enhance service quality, so that customers perceive the shopping experience as being pleasant and even rewarding (Marx and Erasmus, 2006, p.58).

Independent retail food chains are by definition businesses that are privately owned and do not belong to a larger national cooperate chain or group (W&RSETA ILDP Programme, 2011, p.2). They offer a wide range of food and household products and are separated into departments of meat, fresh produce, and dairy, baked goods, canned and packaged goods (Huddleston et al., 2009, p.63). This format relies on a large scale of operations with low-profit margins. To maintain high profits, independent retail food chains try to make up for the low margins with a high overall volume of sales and with sales of higher-margin items (Rao, 2013, p.228).

The retail sector has witnessed significant development in the past ten years from small unorganized family-owned retail formats to organized retailing (Jhamb and Kiran, 2012, p.63). The newly-emerging retail formats are electronic retailing, supermarkets, hypermarkets, and convenience stores. They operate under the concept of everything under the same roof. The concept entails having a large floor space to hold the widest assortment of products and providing a large parking lot for shoppers, implementing a discount pricing policy, and self-service techniques based on effective merchandising and sales promotion (Chamhuri and Batt, 2013, p.102). Modern retailing formats further offer a large variety of products in terms of quality, value for money, and makes shopping a memorable experience characterized by comfort, style, and speed. It further offers customers more control, convenience, and choice along with pleasant experience (Kusuma et al., 2013, p.97).

Contemporary retailing has evolved from being a buying ritual in the exchange process to delivering a joyful shopping experience. Retailing now offers an integrated series of events leading to a pleasurable, involving, relaxing, rewarding, delightful retail customer experience in the shoppers’ life (Bagdare and Jain, 2013, p.790). Retailers are now moving towards a large consumer base with the focus shifted from upper-income consumers to the middle class. The lower-income and middle-income segments are being targeted by a different value proposition of the product, prices, and services (Mehta et al., 2012, p.12). South Africa is also undergoing rapid social and political changes and these changes are affecting the market for retail products, as there is now talk of a South African market rather than a white market or black market (Herdan, et al.,2015, p.101).

Independent food chains play an integral part in the distribution chain of goods and services, uplifting the economy and advancement of the retailing industry (Radder, 1996, p.78). More recently, independent food chains in South Africa have begun entering the townships and expanding into rural areas. The opening of independent food chains has provided exposure to new segments of the population. Whereas many of the independently owned retailers have been seen as being culturally and empathetically linked with their customer base, larger national firms have emphasized issues such as customer service, operational standards, and organizational training (Bruyn and Freathy, 2011, p.538). It is therefore unknown as to what customer service strategies independently owned food chains are embarking on to counter the strategies of national retailers in competing for a shrinking a share of consumers’ wallets, preference, and patronage. Moreover, the customer service phenomenon is increasing, but little is known about its role (Hunter, 2006, p.79).

Customer service is about understanding the needs of different customers, keeping promises, and consistently delivering high product and service standards. The success of any retail entity is determined by customer service (Kimando and Njogu, 2012, p.88), as customer service can heighten the level of customer satisfaction and act as a differentiating factor amongst retailers aiming to have the competitive advantage over their competitors (Srivastava et al., 2015, p.43). It further can increase product quality, gaining profitable opportunities, and eventually increasing sales and income (Jahanshani et al., 2014, p.254).

Recent surveys have also confirmed that consumers think retail customer service is inadequate in retail outlets, and realizing the escalating importance of customer service, an increasing number of retailers have attempted to improve their service strategies (Bishop Gagliano and Hathcote, 1994:60), by improving their service quality to the customers, which has become the basic tool for retailers to enhance the shopping experience, customer satisfaction, revenues, cross-selling and also repeat purchase behaviour (Chandel, 2014, p.176). Delivering high-quality service and having satisfied customers are viewed as indispensable for gaining a sustainable advantage (Shemwell et al.,1998, p.155). However, retailers are still unable to effectively cater to the needs and want of customers and risk not only losing dissatisfied customers to competitors but also experiencing the erosion of profits and consequent failure (Wong and Sohal, 2003, p.496).

Measuring customer service quality in the retail setting is different from any other product or service environment. It for this reason that Dabholkar, Thorpe, and Rentz developed the Retail Service Quality Scale (RSQS) for measuring retail service quality. It should, however, be strongly emphasized that service quality in retailing is different and complicated when seen in any pure service environment, as it incorporates a mix of merchandise and services offered concurrently (Siu and Tak-Hing Cheung, 2001, p.88). This is because of the unique nature of retailing, and as such, improvements or measurements of quality in retailing cannot be approached in the same way as in any services setting. In a retail environment, it is, therefore, necessary to look at quality from the perspective of services as well as goods and derive a set of items that accurately measure this construct.

According to Andreassen and Olsen (2008, p.309), customer service comprises creating and delivering the service in the customer’s presence, providing information, making reservations, and receiving payment. It is an element of the retailer’s market offering that which takes place in all phases of a service’s life-cycle in the pre-purchase phases (e.g. providing information to make a better decision or training customers in using the service), during the purchase (e.g. front-line employees’ service-mindedness, skills, and competencies when attending and responding to customer needs) and post-purchase (e.g. providing information about usage, honouring guarantees or providing repair and spare parts). Customer service is the provision of service to the customers before, during, and after a purchase (Dhammi, 2013, p.124). It is all about the retailer activities that increase the value received by consumers when shopping. Customer services are tangible or intangible value increasing activities that are related to products or services directly or indirectly to meet customer expectations and finally to provide customer satisfaction and loyalty (Kursunluoglu, 2014, p.532).

The customer service process is defined as structured sets of work activities that lead to specified business outcomes for customers (Setia, Venkatesh and Joglekar, 2013, p.567) which can be categorized into three tiers. The first tier is reliability, which means performing the basics well. The second tier is resilience or the ability to respond to failures of the customer service systems. The third tier is referred to as creativity or innovation. Creativity means developing value-added programs for the customers such as direct store delivery or packaging innovations (Theodoras et al., 2005, p.355). Elements of customer service comprise all the external factors that stimulate the consumer’s mind. The interpretation of the individual elements of Customer service is considered a cognitive activity that involves interpretation within established schemata in memory that are based on existing knowledge structures (Marx and Erasmus, 2006, p.58). Customer service can be measured in many dimensions such as service empathy, access time, and courtesy of staff but this study will consider the main dimension of service quality, service speed, and responsiveness (Hassan, 2013, p.81).

Customer service has become a dominant objective for retail managers. In this competitive world, high levels of service have become a minimum requirement for establishing and maintaining a presence in the market (Schary, 1992, p.341). It is how the retailer would like to have the services perceived by customers, employees, and shareholders. It is also referred to as the retailer’s business proposition or customer benefit package, things that provide benefit and value to the customer (Goldstein et al., 2002:123). Customer service is seen as another source of competitive advantage with greater revenue-generating potential among retailers (Sade et al.,2015, p.544). Fallah (2011, p.199) affirms that customer service is a competitive means that differentiate retailers. Customer service greatly affects customer satisfaction and loyalty, which results in the organisation’s profitability. Therefore, providing satisfactory service levels to customers must be the priority for any retailer. Providing high service levels is costly, so it is important to set service levels cost-effectively.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

Research design serves as the framework or plan for a study that guides the collection and analysis of data (Churchill, Brown and Suter, 2010:78). The study employs a mixed-methods research approach, whereby quantitative and qualitative methods are combined because it can potentially capitalize on the respective strengths of both quantitative and qualitative approaches (Ostlund et al., 2011, p.369). A concurrent mixed design is engaged as it is a research design that entails undertaking two or more styles of research at the same or overlapping times, or even at separate times, but as independent enterprises and considered a single phase of research (Kent, 2007, p.255).

This study, however, is mainly quantitative and focuses on an exploratory design. Exploratory research is research that is undertaken to gain background information about the general nature of the research problem or when very little is known about the problem. Exploratory research helps to define terms and concepts and define questions such as “what is the satisfaction with service quality” or to quickly learns that “satisfaction with the service” is composed of several dimensions-tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy. Not only would exploratory research identify the dimensions of satisfaction with service quality, but it could also demonstrate how these components may be measured (Burns and Bush, 2014, p.101).

The quantitative research followed a deductive research process and involves the collection and analysis of numerical data to identify statistical relations of variables (Saunders et al., 2009, p.153). The customer service dimensions generated during the qualitative phase were tested through the use of a questionnaire and fielded amongst a sample drawn from the target population.

A survey was conducted on different days and during different times of the interview days to ensure that a representative sample of the target population was obtained. The respondents were selected and approached while they were shopping at independent food chains.

3.2. Target Population

Cooper and Schindler (2008, p.90) define the target population as those people who dispose of the desired information and can answer the measurement questions. The target population was, therefore, being customers of independent food chains in the Kwa Zulu Natal.

3.3. Sampling Method

A non-probability sampling includes elements from the population selected in a non-statistical manner (Schmidt and Hollensen, 2006, p.166). Convenience sampling was used whereby a non-statistical approach was used primarily because of the absence of a sampling frame. This approach was practiced because almost everybody is a grocery customer, and samples are easier to set up, cheaper in financial terms, and adequate in their representativeness within the scope of the defined research (Cohen et al., 2000, p.102).

3.4. Sample Size

The sample size is defined as the number of elements to be included in a study. In this case, the sample size was 400 respondents as they were considered to provide sufficient input to ascertain findings. The consumer population of Kwa Zulu Natal is over 1 000 000. In support of this sample size, Sekaran and Bougie (2013, p.268) point out that if the population size is 1 000 000, a sample size of 384 should be adequate to support the research findings. 444 respondents were chosen with an average of 6 respondents from each of the 74 stores of independent food chain stores.

3.5. Data Collection

The method of data collection was the survey method. Hawkins, Mothersbaugh and Best (2007, p.750) suggest that surveys are systematic ways of gathering information from a large number of people through the use of questionnaires. Therefore, the survey was done whereby questionnaires were administered to the selected sample to extract detailed information on the topic and clarify complex questions. Graduate assistants were used to administering the questionnaires. These assistants were given training on the subject matter so that they could be able to clarify questions that may arise from the respondents.

The structure of the questions on the questionnaire was kept simple and easy for the respondents to complete with both open-ended and closed-ended questions. The questionnaires were, therefore, administered in each of the 74 stores of the four independent food chain groups, and consent to administer questionnaire was also requested from the three retail groups.

3.6. Data Analysis

Once the data had been captured, several analyses were run on the data. Descriptive statistics in the form of frequency and percentage were computed from the variables. The results were graphically represented using bar and pie charts. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the basic features of the data in the study. They provided simple summaries about the sample and the measures. Together with graphics analysis, they formed the basis of virtually every quantitative analysis of data. Descriptive statistics described what the data should show (Descriptive Statistics, 2006). Inferential statistics were also used to conclude the population. This is generally done through random sampling, followed by inferences made about central tendency, or any of several other aspects of distribution (Inferential Statistics, 2008).

4. Analysis and Discussion of Findings

In terms of age group (Table 1), 29.5% of respondents were between 18-29 years old; 25.0% were between 30-40 years old, 27.5% were between 41-55 years old and 18.0% were between 56-6 and above years old. It is worth noting that in the age category of 30-40 years, 37.8% were male. Within the category of males (only), 26.3% were between the ages of 30 to 40 years. This category of males between the ages of 30 to 40 years formed 9.5% of the total sample.

Table 1. Crosstabs of respondents’ gender distribution by age

| Age in years | Statistics | Gender of respondents | Total | |

| Male | Female | |||

| 18-29 | Count | 49 | 82 | 131 |

| % Age in years | 37.40% | 62.60% | 100.00% | |

| % Gender of respondents | 30.60% | 28.90% | 29.50% | |

| % of Total | 11.00% | 18.50% | 29.50% | |

| 30-40 | Count | 42 | 69 | 111 |

| % Age in years | 37.80% | 62.20% | 100.00% | |

| % Gender of respondents | 26.30% | 24.30% | 25.00% | |

| % of Total | 9.50% | 15.50% | 25.00% | |

| 41-55 | Count | 39 | 83 | 122 |

| % Age in years | 32.00% | 68.00% | 100.00% | |

| % Gender of respondents | 24.40% | 29.20% | 27.50% | |

| % of Total | 8.80% | 18.70% | 27.50% | |

| 56-65 and above | Count | 30 | 50 | 80 |

| % Age in years | 37.50% | 62.50% | 100.00% | |

| % Gender of respondents | 18.80% | 17.60% | 18.00% | |

| % of Total | 6.80% | 11.30% | 18.00% | |

| Total | Count | 160 | 284 | 444 |

| % Age in years | 36.00% | 64.00% | 100.00% | |

| % Gender of respondents | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | |

| % of Total | 36.00% | 64.00% | 100.00% | |

Table 2. Frequency of shopping

| Frequency | Percent | |

| Once a week | 160 | 36.0 |

| Twice in a week | 150 | 33.8 |

| Thrice and more | 134 | 30.2 |

| Total | 444 | 100.0 |

As illustrated in Table 2, 36% of respondents indicated that they did their shopping once in a week, 33.8% of them did their shopping twice in a week and 30.2% did shopping thrice and more in a week. The results imply that the majority of customers visit independent food chains in KwaZulu-Natal more than twice in a week. Maruyama and Trung (2009, p.411) also observed a similar trend in Vietnam and concluded that almost all supermarket consumers shop at least five or six times a week or every day or even more.

As shown in Table 3, the majority of respondents indicated that price was the key influencer on their store choice, followed by the convenience of the retailer, and services offered by the retailer. Munnukka (2008, p.188) further supports the finding that price was an important element that affects store choice. Other influencers of the store as noted by Sinha and Banerjee (2004:483) are the prices offered by the store, nature, and quality of product and service, and customer proximity of residence to the store. It is therefore apparent that the majority of customers shop at independent food chains because of the prices they offer and convenience.

Table 3.Key factors that influence customer’s store choice

| Frequency | Percent | |

| Prices offered by the retailer | 252 | 56.8 |

| The convenience of the store | 101 | 22.7 |

| Services offered by the store | 53 | 11.9 |

| Other | 38 | 8.6 |

| Total | 444 | 100.0 |

Table 4. Factors that describe good customer service offered by retailers

| Frequency | Percent | |

| Helpfulness of store staff | 81 | 18.2 |

| Complementary services offered by the retailer (ATM terminal, parking, and toilets) | 88 | 19.8 |

| The appearance of the store (cleanness, good product display, and presentation) | 84 | 18.9 |

| Store operating hours (extended hours) | 57 | 12.8 |

| Facilities for shoppers with special needs (physical handicapped, wheelchaired or translators) | 45 | 10.1 |

| Ability by the retailer to offer customers credit | 40 | 9.0 |

| Providing wide product assortment | 49 | 11.0 |

| Total | 444 | 100.0 |

As depicted in Table 4, customers were then again asked to rank what they would consider good customer service offered by independent food chains. Complementary services offered by the retailer included ATM terminals, parking, and toilets which constituted 19.8%, the appearance of the store made 18.9%, helpfulness of store staff 18.2%, store operating hours 12.8%, product assortment 11%, facilities for shoppers with special needs (physical handicapped, wheel-chaired or translators) 10.1% and ability by the retailer to offer customers credit constituted 9%. It is worth noting that the majority of customers perceived complementary services offered by retailers to be good customer service practices. It is therefore recommended that independent food retailers further adjust their setting and offer more complimentary service to allure more consumers into an unplanned purchase, thus boosting the sale volume and profits. Retailers should further place more attention on keeping the fresh and healthy shopping atmosphere as this will entice consumers to stay longer and become more loyal to the retailer (Cho, Ching and Luong, 2014, p.46)

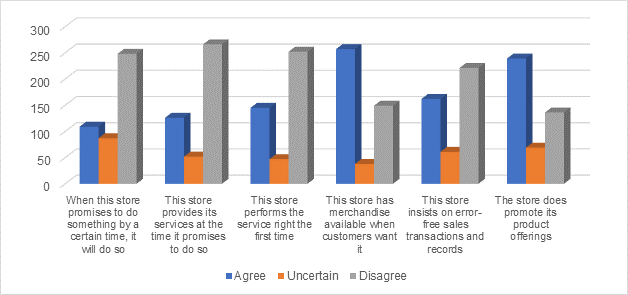

With regards to the respondents’ perceptions of the reliability of services provided by the independent food chain stores, results were statistically different. As reflected in Table 5 there were significant differences in opinions concerning the perceived reliability of services. Despite the differences, respondents’ opinion was mostly negative with the average level of disagreement indicated as 47.7%. A point deserving mention is that the majority (57.9%) of the respondents agreed that independent food chain stores had merchandise available when customers wanted it.

Table 5.Respondents’ scoring pattern on the reliability of service provided by independent food chains

| Question item | Agree | Uncertain | Disagree | Chi-Square | |||

| Count | Row N % | Count | Row N % | Count | Row N % | p-value | |

| When this store promises to do something by a certain time, it will do so. | 109 | 24.50% | 87 | 19.60% | 248 | 55.90% | 0.000 |

| This store provides its services at the time it promises to do so. | 126 | 28.40% | 52 | 11.70% | 266 | 59.90% | 0.000 |

| This store performs the service right the first time. | 145 | 32.70% | 49 | 11.00% | 250 | 56.30% | 0.000 |

| This store has merchandise available when customers want it. | 257 | 57.90% | 38 | 8.60% | 149 | 33.60% | 0.000 |

| This store insists on error-free sales transactions and records. | 162 | 36.50% | 61 | 13.70% | 221 | 49.80% | 0.000 |

| The store does promote its product offerings. | 238 | 53.60% | 70 | 15.80% | 136 | 30.60% | 0.000 |

Figure 1. Respondents’ average level of disagreement on the reliability of services provided by independent food chains

With regards to problem-solving abilities at the independent food chains, the Chi-square analyses yielded a statistically significant relationship (p <0.05) in all the statements in Table 6. Specifically, and as shown in Figure 5.5, 39.9% of the respondents disagreed that the store willingly handles returns and exchanges. More so, 50.9% of the respondents believed that when a customer has a problem, the store does not show a sincere interest in solving it. Similarly, 51.6% of them believed that the employees at independent food chain stores could not handle customers’ complaints directly and immediately. As such, it was understandable that 45.5% of the respondents disagreed that employees resolved customers’ complaints speedily, efficiently, and fairly. This is a matter of concern particularly as 45.0% of the respondents thought that the stores do not seek customers’ opinions and suggestions.

Overall, there was general disagreement amongst the respondents on the problem-solving abilities of independent food chain stores with the level of disagreement given as 45.65%. Notwithstanding this, and in terms of the accessibility of the independent food chain stores, 46.2% of the respondents were in agreement that the store was easily accessible.

Table 6. Respondents’ scoring pattern on problem-solving at independent food chains

| Question item | Agree | Uncertain | Disagree | Chi-Square | |||

| Count | Row N % | Count | Row N % | Count | Row N % | p-value | |

| This store willingly handles returns and exchanges. | 125 | 28.2% | 142 | 32.0% | 177 | 39.9% | 0.009 |

| When a customer has a problem, this store shows a sincere interest in solving it. | 143 | 32.2% | 75 | 16.9% | 266 | 50.9% | 0.000 |

| Employees in this store can handle customer complaints directly and immediately. | 138 | 31.1% | 77 | 17.3% | 229 | 51.6% | 0.000 |

| Employees resolve customers’ complaints speedily, efficiently, and fairly. | 175 | 39.4% | 67 | 15.1% | 202 | 45.5% | 0.000 |

| The store does seek customers’ opinions and suggestions. | 141 | 31.8% | 103 | 23.2% | 200 | 45.0% | 0.000 |

| The store is easily accessible. | 205 | 46.2% | 58 | 13.1% | 181 | 40.8% | 0.000 |

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Customer service

Findings have shown that customer service at independent retail food chains in KwaZulu-Natal is one of the crucial factors which has to be improved. The majority of customers have shown that independent retail food chains in KwaZulu-Natal do not provide them with good or efficient customer service. It is recommended that independent retail food chains study their customer profiles as it was evident during interviews that customer profiling or segmentation was not being undertaken in detail. A retailer that profiles its customers is a market-driven organization, which implies that the retailer knows its customers and market thoroughly. As a result, a market-driven retailer will be able to service its customers and consistently win in the markets it operates within (Brondoni, Corniani and Riboldazzi, 2013, p.29).

Retailers should also identify and establish customer service needs and requirements to facilitate proper product and service mix design. Identifying and meeting customer service needs helps retailers to remain competitive in the market (Wang and Ji, 2010, p.137). Retailers should, therefore, obtain precise information on the service needs of customers and then use that information to among other things, tailor products and services to meet the service needs of their customers. This will, in the long run, reduce costs of the retailer, improve customer service and profitability (Toombs and Bailey, 1995, p.20).

Retailers are also recommended to keep up regular communication with customers to inform them about promotions or any new developments taking place. Communicating with customers allows retailers to provide detailed product information or persuade, incite, and remind consumers about their offerings (Keller, 2001, p.823). The majority of respondents indicated that there was no form of communication they received from independent retail food chains. It is highly recommended that retailers make use of social media, short message service (SMS), and other different forms of electronic communication platforms to convey their message to their customers. Social media allows companies to connect with customers, forge relationships with existing as well as new customers while using richer media with greater reach (Sashi, 2012, p.225).

On investigation, retailers did not have well-defined customer feedback and complaints handling mechanisms, and it is therefore recommended that retailers devise a strategy on how to seek service feedback and handle complaints from customers. Such a strategy will ensure effective and efficient complaint resolution is achieved and lead to enhanced customer satisfaction (Lam and Dale, 1999, p.844). Seeking feedback will further provide retailers with rich information on how to improve their services in the long run.

Current customer service tools employed by independent food chains

Customers indicated that their main motive for making purchases at independent retail food chains was the price, it is of most concern as price alone cannot guarantee long term survival of the retailer. Amongst some of the services offered by retailers, few include social grant payments, insufficient parking, unclear returns policy, non-existent restrooms, and financial services. It is highly recommended that independent retail food chains in KwaZulu-Natal offer the following services:

Introducing customer loyalty programs

Customer loyalty programs are a tactical marketing strategy that a retailer implements in a bid to retain profitable customers by diverting their attention from purchasing and using competing retailers (Basera, 2014, p.3). Customer loyalty programs are the most successful way to get more business from existing customers and to entice them to buy more often from the same retailers (Robinson, 2011, p.1). Loyalty programs further provide an opportunity for profiling customers and the ability to know of their product and service needs as well as preferences.

5.1. Recommendations for Further Research

It is recommended that other studies using a survey and observation method be done that will explore and discover, in-depth, more about retail customer service. It was also noted that some respondents needed to say more about customer service and service quality but the questionnaire was not designed in a manner that allowed them to elaborate. Therefore, further research is recommended.

This study has highlighted the applicability of customer services amongst the independent food chain in KwaZulu-Natal. Key issues about retail service quality, customer satisfaction, loyalty, and trends in the South African retail landscape were discussed. It is believed that the importance of customer service is at an all-time high in major corporate chain stores. In today‘s volatile economy, providing excellent customer service can be the critical difference in any company’s success. With ever-changing customer demands in the retail industry, retailers face an ongoing challenge in gaining a competitive advantage by creating added customer value. In order to accomplish this value, retailers have to constantly review their customer service strategies.

References

- Andreassen, T.W. and Olsen, L.L., 2008. The impact of customers' perception of varying degrees of customer service on commitment and perceived relative attractiveness. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 18(4), pp. 309-328.

- Bagdare, S. and Jain, R., 2013. Measuring retail customer experience. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 41(10), pp.790-804.

- Beneke, J., Hayworth, C., Hobson, R. and Mia, Z., 2012. Examining the effect of retail service quality dimensions on customer satisfaction and loyalty: The case of the supermarket shopper. Acta Commercii, 12(1), pp. 27-43.

- Bishop Gagliano, K. and Hathcote, J., 1994. Customer expectations and perceptions of service quality in retail apparel specialty stores. Journal of Services Marketing, 8(1), pp. 60-69.

- Bruyn, P.D. and Freathy, P., 2011. Retailing in post-apartheid South Africa: the strategic positioning of Boardmans. International journal of retail & distribution management, 39(7), pp. 538-554.

- Burns, A.C. and Bush, R.F., 2014. Marketing Research. 3rd edn. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education Inc.

- Chamhuri, N. and Batt, P.J., 2013. Exploring the factors influencing consumers’ choice of retail store when purchasing fresh meat in Malaysia. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 16(3), pp.99-122.

- Chandel, S.J., 2014. Service quality and customer satisfaction in organised retail sector in India. International Journal of Marketing and Technology, 4(7), pp. 176-189.

- Chiliya, N., Herbst, G. and Roberts-Lombard, M., 2009. The impact of marketing strategies on profitability of small grocery shops in South African townships. African Journal of Business Management, 3(3), pp. 70.

- Churchill, G.A., Brown, T.J. and Suter, T.A., 2010. Basic Marketing Research (7th edn). New York: Cengage Learning.

- Cooper, D.R. and Schindler, S.P., 2008. Business Research methods (10th edn). Boston: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

- Descriptive Statistics, 2006. Research Methods knowledge Base [online] Available at: http://socialresearchmethods.net/kb/statdesc.php [Accessed 23 April 2009].

- Dhammi, B.R.L., 2013. Customer service provided by organised retail in India: Customers’ perception. International Journal of Marketing and Technology, 3(2), pp. 124-131.

- Du Plooy, A.T., De Jager, J.W. and Van Zyl, D., 2013. Drivers of perceived service quality in selected informal grocery retail stores in Gauteng, South Africa. Southern African Business Review, 16(1), pp. 94-121.

- Fallah, S., 2011. Customer Service. Logistics Operations and Management. Tehran: Elsevier, pp.199-218.

- Goldstein, S.M., Johnston, R., Duffy, J. and Rao, J., 2002. The service concept: The missing link in service design research. Journal of Operations Management, 20(2), pp. 121-134.

- Hassan, I.A.Y., 2013. Customer service and organizational growth of service enterprise in Somalia. Educational Research International, 2(2), pp. 79-88.

- Herdan D.E., Abratt R., Bendixen M., 2015. Cross Cultural Analysis of Factors Affecting Consumer Patronage: Implications for South African Retailers. In: Gomes R. (eds) Proceedings of the 1995 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference - Developments in Marketing Science, Springer, Cham. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-13147-4_26

- Huddleston, P., Whipple, J., Nye Mattick, R. and Jung Lee, S., 2009. Customer satisfaction in food retailing: Comparing specialty and conventional grocery stores. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 37(1), pp. 63-80.

- Hunter, J.A., 2006. A correlational study of how airline customer service and consumer perception of airline customer service affect the air rage phenomenon. Journal of Air Transportation, 11(3), pp. 78-109.

- Inferential Statistics, 2008. Online statistics: An interactive multimedia course of study [online] Available at: http://onlinestatbook.com/glossary/inferential_statistics.html [Accessed 23 April 2017].

- Jahanshani, A.A., Hajizadeh, G.M.A., Mirdhamadi, S.A., Nawaser, K. and Khaksar, S.M.S., 2014. Study the effects of customer service and product quality on customer satisfaction and loyalty. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1(7), pp. 253-260.

- Jhamb, D. and Kiran, R., 2012. Trendy shopping replacing traditional format preferences. African Journal of Business Management, 6(11), pp. 41-96.

- Kent, R., 2007. Marketing Research: Approaches, Methods and Applications in Europe (1st edn). London: Thomson Learning.

- Kimando, L.N. and Njogu, M.G.W., 2012. Factors that affect quality of customer service in the banking industry in Kenya: A Case Study of Postbank head office Nairobi. International Journal of Business and Commerce, 1(10), pp. 82-105.

- Kimani, S.W., Kagira, E.K., Kendi, L. and Wawire, C.M., 2012. Shoppers perception of retail service quality: Supermarkets versus small convenience shops (Dukas) in Kenya. Journal of Management and Strategy, 3(1), pp. 55-66.

- Kursunluoglu, E., 2014. Shopping centre customer service: Creating customer satisfaction and loyalty. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 32(4), pp. 528-548.

- Kusuma, B., Prasad, N.D. and Rao, M.S., 2013. A study on organized retailing and its challenges and retail customer services. Innovative Journal of Business and Management, 2(5), pp. 97-102.

- Marx, N.J. and Erasmus, A.C., 2006. An evaluation of the customer service in supermarkets in Pretoria East, Tshwane Metropolis, South Africa. Journal of Consumer Sciences, 34(1), pp. 56-68.

- Mehta, D., Mehta, N.K. and Sharma, J., 2012. Indian organized retail sector: Impediments and opportunities. Oeconomics of Knowledge, 4(5), pp. 8-17.

- Mower, J.M., Kim, M. and Childs, M.L., 2012. Exterior atmospherics and consumer behavior: Influence of landscaping and window display. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 16(4), pp. 442-453.

- Radder, L., 1996. The marketing practices of independent fashion retailers: Evidence from South Africa. Journal of Small Business Management, 34(1), pp. 78-84.

- Rao, B.V., 2013. Organized retailing: Poised for rapid growth. International Journal of Retailing & Rural Business Perspectives, 2(1), pp. 227-229.

- Sade A.B., Bojei B.J., Donaldson G.W., 2015. Customer Service: Management Commitment and Performance within Industrial Manufacturing Firms. In: Sidin S., Manrai A. (eds) Proceedings of the 1997 World Marketing Congress. Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science. Springer, Cham. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-17320-7_141

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A., 2009. Research Methods for Business Students (5th edn). London: Prentice Hall.

- Schary, P.B., 1992. A concept of customer service. Logistics and Transportation Review, 28(4), pp. 341-352.

- Setia, P., Venkatesh, V. and Joglekar, S., 2013. Leveraging digital technologies: How information quality leads to localized capabilities and customer service performance. MIS Quarterly, 37(2), pp. 565-590.

- Shemwell, D.J., Yavas, U. and Bilgin, Z., 1998. Customer-service provider relationships: An empirical test of a model of service quality, satisfaction and relationship-oriented outcomes. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 9(2), pp. 155-168.

- Srivastava, M., Goli, S., Bhadra, S. and Kamisetti, T.K., 2015. Customer service quality at retail stores in Hyderabad airport. Indian Journal of Commerce and Management Studies, 6(3), pp. 43-52.

- Steven, A.B., Dong, Y. and Dresner, M., 2012. Linkages between customer service, customer satisfaction and performance in the airline industry: Investigation of non-linearities and moderating effects. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 48(4), pp. 743-754.

- Theodoras, D., Laios, L. and Moschuris, S., 2005. Improving customer service performance within a food supplier-retailers context. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 33(5), pp. 353-370.

- Tlapana, T.P., 2017. Customer service as a strategic tool amongst independent retail food chains in KwaZulu-Natal (Doctoral dissertation), Durban University of Technology, South Africa.

- Ostlund, U., Kidd, L., Wengstrom, Y. and Rowa-Dewar, N., 2011. Combining qualitative and quantitative research within mixed method research designs: A methodological review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48, pp.369-383.

- W&RSETA ILDP Programme, 2011. Independent food retailers in the Republic of South Africa. Can they ensure sustainability in an evolving retail landscape [online]. Available at: http://www.wrseta.org.za/downloads/ILDP/Imitha%20Final.pdf [Accessed 24 January 2017].

- Wong, A. and Sohal, A., 2003. Service quality and customer loyalty perspectives on two levels of retail relationships. Journal of services marketing, 17(5), pp. 495-513.

Article Rights and License

© 2020 The Author. Published by Sprint Investify. ISSN 2359-7712. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.