Keywords4th industrial revolution banking safety consumer behaviour digital banking e-banking financial technology online banking personal banking service quality South Africa

JEL Classification G21, L86, M31, O33

Full Article

1. Introduction

With constant technological advancement, consumers have become progressively more conscious of the wide range of products and services that are offered to them, which have resulted in intense competition among companies. The Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) has introduced customers to significant new ideas and methods of banking and has allowed companies to offer new and exciting product and service offerings seamlessly, many of which can be classified under the mantle of ‘digitization of banking’ (Ohene-Afoakwa and Nyanhongo, 2017; Ajibade and Mutula, 2020; Lauren, 2022).

The impact of digitization of banking is discussed in detail in this paper, along with the growth of cashless services, e-commerce, and digital advertising of banking. Gleason (2018) describes the impact of the 4IR in mobile banking, noting that it appropriately applies to both the technological changes and how people adapt and live with these constant changes. It has become clear that people will only adopt new technology trends that benefit them. During the first two decades of the 21st century, the use of mobile devices has increased dramatically (Carbonell et al., 2013; Adamczewska-Chmiel et al., 2022). This is confirmed by Kayembe and Nel (2019), who point out that the 4IR includes typical characteristics of an advanced digital technology sector, namely powerful sensors, artificial intelligence, and machine learning.

An initial review of literature showed that there is significant research on the core factors of digital banking in many other counties but seemed to be lacking for SA. A number of these articles point out that while SA does have an advanced banking system (e.g., Ramavhona and Mokwena, 2016), the lack of research on digital banking is due mainly to the slow growth and adoption of digital banking in SA as opposed to the rapid growth of digital banking in other countries (Louw and Nieuwenhuizen, 2020). This clearly indicates a need for more research into digitalisation of banking in SA and into the factors that encourage adoption of digital banking, especially from the consumer viewpoint. To assist with such further research, we decided to conduct a systematic literature review to highlight gaps in the knowledge and provide a starting point for future research on the topic.

The body of your paper should start with an introduction that presents the specific problem under study and describes the research strategy. State the reasons why the problem deserves new research. Discuss different points of view from relevant related literature, but do not feel compelled to include an exhaustive historical account. Develop the problem with enough breadth and clarity to make it generally understood by as wide a professional audience as possible.

2. Research Objectives and Methodology

2.1Research Objectives and Questions

The overall aim of this paper is to establish, based on extant literature, possible factors that influence the adoption and use of personal digital banking in a developing country, since most such research has occurred in developed economies. To achieve this aim, two research objectives were set: (1) To identify extant literature, both scholarly and practitioner, which discusses digital personal banking and helps to define the issues that encourage consumers to adopt such banking methods; (2) To identify a list of possible factors that are likely to be drivers of the adoption and use of digital personal banking in a developing country. To direct the achievement of these objectives, an overarching research question was set, namely: “What are possible constructs that encourage the preference for, and use of digital personal banking in a developing country?

The purpose of this paper was to investigate and identify possible drivers of the preference for digitized personal banking in a developing nation. As a template for this research, South Africa was selected as the developing country, as it has a sophisticated banking system (Ramavhona and Mokwena, 2016) and is accepted as a developing nation (Marnewick and Bekker, 2022). Since many studies have indicated the importance of consumer perceptions for the adoption of digital banking (e.g., Ananda et al., 2020; Mufingatun et al., 2020) an emphasis on the perceptions of digital banking by SA consumers was the obvious focus. Therefore, a comprehensive literature review was needed to create a picture of the current state of banking digitization, from the customers viewpoint, to identify what the key success factors for successful adoption of digital banking are. Clarification of this research question would thus establish a starting point for a future research stream in this field.

2.2. Research Methodology

The research procedure and methodology was based upon the USA’s National Institutes of Health’s PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework, which provides a protocol structure for conducting a systematic literature review. The structure consists of eight steps (Kahn et al., 2003; Majumder, 2015), but provides insufficient details about extracting and analysing the data. Therefore, for this step the guidelines provided by Ramdhani et al. (2014) were used:

1. Develop a research question

2. Define inclusion and exclusion criteria

3. Locate studies

4. Select studies

5. Assess study quality

6. Extract data

7. Analyse and present results

8. Interpret results

2.2.1. Define Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Qualitative descriptors were identified as inclusion criteria for the research, namely digital banking convenience, practical quality, service quality, usability, safety, risk and preference, and consumer experience. These inclusion criteria were identified throughout the literature search by analysing scholarly and ‘grey’ literature articles and the reference sections of these articles. Reference sections from the relevant articles were used to identify additional articles, which equates to a snowball sampling approach. This method ensured both a local and an international comparison of the topic.

Documents selected for inclusion were evaluated based on:

(a) how old the source was – newer than 10 years was acceptable (about 95% of references) but newer than 5 years preferred (about 77% of references),

(b) whether the source aligned with the research objectives, in other words whether it addressed digitalisation and/or banking, especially from a consumer viewpoint

(c) the credibility of the source, i.e., whether a scholarly journal or academic conference or thesis, which are peer reviewed, a government source or a recognised news source,

(d) only sources in the English language.

Articles dealing with banking systems without reference to digital banking where excluded, as were most articles older than 10 years or not in English.

2.2.2. Locate Studies

The comprehensive search and initial scanning of peer-reviewed journals and other publications was based on various key terms including Digital Banking, Online Banking, Cashless Transactions, Digitalization, Covid-19, and The Fourth Industrial Revolution. This initial search was of databases and publications including Aosis Publishing (SAJEMS, SAJIM), Researchgate, SABINET, SA Government Gazettes, Statistics SA, and Google Scholar. Key word searches were initially conducted individually, i.e., each key word was searched for alone. Thereafter, all the key words were searched for together via a Boolean and/or search.

The initial documents identified as potentially useful are shown, according to the source characteristics, in Table 1.

Table 1: Documents Identified from Literature Search

| Type of literature | No. identified |

| Scholarly journal articles | 84 |

| Books/textbooks | 7 |

| Newspapers/magazines/internet newspapers/Internet blogs | 7 |

| Theses/dissertations | 6 |

| Business reports/patent application | 5 |

| Government publications | 3 |

| Academic conference papers | 2 |

| Other publications | 2 |

2.2.3. Select Studies

Initial searches of the located publications identified 134 potential documents, and after detailed reading and analysis of these 134 publications, 18 were rejected as they did not concern digital banking or digitisation sufficiently, or were not considered sufficiently reliable. The review thus resulted in the inclusion of 116 documents, 84 of which were scholarly journal articles and 32 of which were from more practitioner oriented websites, textbooks, and government publications. The 84 scholarly articles were further analysed for appropriate content as per the objectives and key terms and were assessed as per the following criteria: ‘Covered In-Depth’, ‘Covered Partially’, ‘Covered Poorly’, or ‘Not Covered’. Following this analysis only 35 of the 84 papers were specific to digital banking or digitisation, whereas the remaining 49 covered broader general theory issues, which have been used in the study to provide needed background and context to the literature and the study. These less directly relevant papers covered issues such as the fourth industrial revolution, technology, e-commerce, economics, marketing, consumerism, service quality, perception of services and broader aspects of banking. The 35 papers specific to digital banking and digitisation, their compositional constructs and an assessment of their coverage and relevance to the core inclusion criteria, are listed in Table 2.

Table 2: Comparison of South African Versus International Literature on Factors Contributing to Digital Banking

| Author/s | General digital banking | Conve-nience | Practical quality | Branch service quality | Usability | Safety | Online service quality | Risk and preference | Consumer experience |

| South Africa | |||||||||

| Achieng and Malatji (2022) | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ |

| Adefulu and Van Scheers (2016) | --- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓✓ |

| Ajibade and Mutula (2020) | ✓ | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | ✓ | ✓ |

| Chigada and Hirschfelder (2017) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓ | --- | --- |

| Louw and Nieuwenhuizen (2020) | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ |

| Moyo (2018) | --- | --- | --- | ✓ | --- | --- | ✓ | --- | --- |

| Msweli and Mawela (2020) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Simatele (2015) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | --- | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓ |

| Slazus and Bick (2022) | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | --- | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ |

| International | |||||||||

| Aghaei (2021) | ✓✓ | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓✓ | --- | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ |

| Adamczewska-Chmiel et al. (2022) | ✓✓ | --- | --- | --- | ✓ | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Ahmad et al. (2021) | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓✓ | --- | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓✓ |

| Al-Salaymeh (2013) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ananda et al. (2020) | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓ |

| Mbamba (2018) | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓ |

| Deora (2018) | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | --- |

| Fabris (2019) | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Gharbi and Kammoun (2022) | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ | --- | --- | ✓ | --- | --- | --- | ✓ |

| Hammoud et al. (2018) | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓✓✓ | --- | ✓✓✓ |

| He et al (2022) | --- | --- | ✓ | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | ✓ |

| Khando et al. (2022) | ✓✓ | ✓ | --- | --- | ✓✓ | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Lauren (2022) | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓✓ | --- | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ |

| Mieszkowska (2022) | --- | --- | --- | ✓ | --- | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓✓ |

| Menon (2019) | ✓ | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ |

| Mohd and Pal (2020) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Mufingatun et al. (2020) | ✓ | ✓ | --- | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓✓ |

| Munusamy et al. (2012) | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | --- | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ordu and Anyanwaokoo (2016) | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | --- |

| Ouyang (2022) | ✓✓✓ | --- | ✓✓ | --- | ✓✓ | --- | --- | ✓✓ | ✓✓ |

| Ramyah et al. (2006) | ✓ | --- | --- | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓✓ | --- | --- |

| Revathi (2019) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Shankaraiah and Mahipal (2021) | ✓✓✓ | --- | --- | --- | ✓✓✓ | --- | --- | --- | ✓ |

| Taher (2021) | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Uddin et al. (2014) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓✓ |

| Yalçin-Incik and Incik (2022) | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓✓ | --- | ✓✓ | --- | --- |

Note: Covered In-Depth: ✓✓✓; Covered Partially: ✓✓; Covered Poorly: ✓; Not Covered: ---

In Table 2 articles listed according to digital banking in South Africa (SA) to international research on digital banking (any country other than SA), as well as recording their coverage of the factors that contribute to digital banking. The table shows that while there exists research on banking and digital banking in SA, there is very little such research, and what there is, is not comprehensive in coverage of all the core factors that encourage the adoption of digital banking.

2.2.4. Study Quality

Several procedures were followed to ensure a high-quality review of the literature. However, while ensuring the quality of data analysed, complexities arose due to the lack of sources on digital banking in SA. Despite an advanced banking system in SA, there exists very little research on the prevalence of digital banking in SA. Much of the data is from grey literature, such as newspapers, technical reports, practitioner magazines, unpublished studies and governmental research, which lack a peer-review process. Sources such as dissertations, conference papers and abstracts are also considered grey literature, although, having been examined or editorially reviewed, are considered more trustworthy than other types of grey literature. According to Majumder (2015, p. 1), “grey literature is a significant part of a systematic review… because grey literature is often more current than published literature and is likely to have less publication bias”. Therefore, those from sources that were reputable or with well-cited references were included, even if not fully peer reviewed. “Reputability” was subjectively assessed, for example, based on whether the source was a recognised newspaper, a government document or any other document that was in some way 'assessed’, ‘examined’, ‘edited’ or checked before publication. Thus, individual opinion pieces or blogs from the Internet, for example, were excluded.

Therefore, this literature review was based on a mix of scholarly, peer reviewed literature and grey literature, although the predominance is from scholarly peer reviewed documents, as can be seen in Tables 1 and 2. Grey literature was necessary to cover gaps in the scholarly literature and to ensure current up-to-date coverage and comprehensiveness, which is essential when examining a cutting edge and rapidly changing topic like digitalisation. Furthermore, grey literature reduces publication bias, which McDonagh et al. (2000, p. 9) define as “the failure to publish research on the basis of the nature and directional significance of the results.” Thus, inclusion of grey literature can produce more reliable results.

2.2.5. Extracting and analysing data from the literature

Having identified relevant documents, they were then read in detail and categorised according to location (South Africa versus international) and their contribution to, and coverage of, the core issues being researched, as illustrated in Table 2. From each document, relevant data or extracts were recording in an MS Word table, listed according to the core issues. Thereafter, the collected data was summarised narratively, using the approach suggested by Lee (1999) of deconstructing the data into a more simplified structure, and then reconstructing it, in this case according to the study’s core issues.

2.2.6. Present and interpret results

The final steps of the PRISMA protocol (present results – step 7 and interpret results – step 8) are presented in the following sections, namely Sections 3 to 7, starting with an exposition of digitalisation in banking and an overview of the SA banking context. This is followed by the presentation of the findings according to constructs that make up the core issues of this study.

3. Digitalisation of Banking

Lee et al. (2018) state that there are two prominent drivers of the 4IR. First, the advancement of the motor industry from the pre- to the post- Fordism Era, and second, the development of the digital world, the Internet and mobile technology, i.e., all applications and infrastructures related to the Web. From early in the 21st Century, particularly during the 2010’s decade, digital banking has grown tremendously. Digital technology, the use of smartphones, and the Internet have significantly influenced banking behaviour, which itself is a result of newer technology, and has made banking services more accessible.

In an earlier study by Ngandu (2012), it was found that the adoption of electronic banking is likely to increase only when customers consider internet banking to be a simple process. However, a more recent study by Ananda et al. (2020) found that the adoption of digital banking is not significantly influenced by how easy it is to use, but rather by the perceived usefulness, i.e., how useful digital banking may be to the consumer. This is also referred to as the performance expectation (Mufingatun et al., 2020), because a higher level of satisfaction, and the rating thereof, will result from banking applications that incorporate a diverse list of essential banking services that fulfil a customer’s expectation. It may also be because banking customers have become more digitally ‘savvy’ and more confident in computer use since 2012.

3.1 Cashless Transactions

In recent times, consumers tend to avoid carrying large sums of cash due to safety concerns (Raja, 2018; Kaur, 2019; Mohd and Pal, 2020). Husain (2017) and Khando et al, (2022) state that cashless transactions involve purchasing goods and services where there is no actual cash involved. The cash is instead substituted by several cashless methods that are driven by digital technology and are capable of transferring money from one person’s bank account to another person or to a business. He goes on to discuss the use of cheques, which were one of the first ‘cashless’ transactions, but notes that a cashless society is not so easily achieved. Ehrlich and Elliott (2019) states that for a wide variety of consumers, cash is instant, easy to accept without fees or complications, and can be easily spotted if fake. Also, using cash does not require consumers to have knowledge of, or require, digital technology and the Internet.

Indicators of a cashless society depend on different factors. For instance, governments and several companies provide strong encouragement and support for cashless transactions (Khan and Craig-Lees, 2009; Ouyang, 2022). Commonly, due to high crime rates and complaints filed by consumers, companies, particularly banks, will promote the use of cashless transactions. One of the major contributions to the promotion of cashless transactions falls within the third generation (3G) and fourth generation (4G) networks that have allowed fast and seamless internet connectivity. Banks use this technology to their advantage, by releasing convenient banking applications that can provide basic and advanced transactions without going to a bank or ATM to draw cash. Some further indicators of a cashless society are:

Financial accessibility. A driving factor to promote the use of cash or non-cash transactions is the actual accessibility to cash (Jumba and Wephukhulu, 2019). Countries with high unemployment and inequality will have more people using physical cash as opposed to using a bank.

Preferences and technology.Jain (2017) posits that the middle class in Africa has seen a significant digital transformation, which is seen as a business opportunity for global retailers. His study further points out that SA consumers are fast becoming influenced by materialism and reveals that E-commerce is rapidly growing in Africa, which has allowed international brands to take advantage of this transformation from a business perspective. This is further discussed by Achieng and Malatji (2022), who state that in South Africa improved mobile telecommunication infrastructure and the Internet, particularly mobile broadband networks, serve as the foundation for the rise of digital initiatives. These changes have fundamentally altered the manner in which individuals work, communicate, access government services, and conduct business.

Positive and negative aspects of cashless transactions. With the introduction of digital banking, banks have begun to highlight the benefits of transacting without cash. For instance, with regard to the law, Fabris (2019) discusses the impact of having less cash circulating in society, stating that “the elimination of cash may seriously impair criminal activity, especially those connected with drugs and money laundering. These activities can be hardly carried out without cash”. Deora (2018) points out that tax evasion will drastically decrease, as the government and financial institutions can easily track the income of citizens. Ordu and Anyanwakoro (2016), Parma (2018), and Ahmad et al. (2021),discuss the safety and peace of mind for consumers, noting that cashless societies experience a reduction in robberies and theft at ATM’s and other public spaces.

3.2 E-commerce

E-commerce is defined by Ndayizigame (2013) as the distribution of business intelligence, maintaining organizational relations, and overseeing business transactions by employing Internet-based technology, while Shankaraiah and Mahipal (2021) state that e-commerce falls under the broader scope of e-business and is commonly recognized as a direct selling method. It operates through online platforms to receive orders and facilitates the direct shipment of products from manufacturers to end users, bypassing the involvement of middlemen in the supply chain. Additionally, Khan (2016) states that e-commerce also serves as a reliable indication of the prices of different products and services, allowing consumers to ‘shop around’ before making a purchase decision. In banking, e-commerce allows businesses to use advancements in mobile technology to improve customer service by expanding their market reach, improving relationships, and offering a wider range of products and services. Azeem et al. (2015) identifies three types of e-commerce - business to business, business to customer, and customer to customer. In digital banking, banks focus on the business to consumer concept that incorporates the use of e-banking. Azeem et al. (2015) further identifies that e-banking incorporates digital banking, in addition to advancements in ATMs, EFT, and direct deposits. Previous studies, such as by Havasi et al. (2013) and Fatonah et al. (2018), highlight that advancements in technology positively impact e-banking, but it is generally the wealthier sector of the population that are first to experience and adapt to these changes. This is due to the segment having the financial means to keep up with technology. Banks are imperative to every country’s economy, which is why a well-developed banking sector needs to incorporate the needs of all their clients, and not just those who have the means to access their newer services. Khan (2016) and Hammoud et al. (2015) state that if e-commerce is implemented widely and efficiently, advancements in technologies can result in business process improvements, which positively impacts its consumer base and customer satisfaction. This is further discussed by Taher (2021), who discusses additional benefits that improvements from e-commerce present to both consumers and businesses, such as product accessibility, price comparisons, increasing efficiency in business operations, and easier target marketing.

3.3 Digital Advertising and its Effects on Digital Banking

Constant technological advancement has resulted in consumers becoming increasingly aware of the wider range of products and services that are offered to them (Murugan, 2019), which makes competition amongst companies widespread (Wojcik et al., 2018; Clark and Monk, 2017). Following the impact of the 2008 global economic depression, banks needed to find new and innovative ways to attract and retain their clients. This did not solely entail building trust and credibility, but to rather market their products in such a way that consumers are drawn to not only the products and services of the bank but to the image and branding of the company itself (An et al., 2018). This is where digital advertising became a critical factor in the success of banking in the 2010’s decade. One major difference between traditional and digital advertising is that digital advertising reaches users in a very subtle manner through what Information Technology defines as an Ad Server. Sankuratripati et al. (2006), and Zawandzinksi (2018) refer to an Ad Server as the technology used online to place advertisements on websites. These Ad Servers allow advertisements to be made visible to users even when they do not intend to shop for that product or service, allowing for the possibility of customers to be drawn to a purchase they had no intention of making. Although traditional marketing can still prove highly effective for existing and former clients in banking, digital advertising and marketing can help target new audiences much faster using Ad Servers. For instance, younger generations are more attracted to the use of digital technology (Turner, 2013; Beaven, 2014; Linnes and Metcalf, 2017; Venter, 2017; Yalcin-Incik and Incik, 2022), which allows banks and other companies to capture and analyse data on this audience and helps these businesses to build more specific marketing segments. This makes it easier to draw in a newer generation of clients, most of whom are already comfortable with the use of digital technology.

4. Banking in South Africa

4.1 Changes to Banking in South Africa

Regulatory changes, technological advancements, competition, and opportunities and threats have significantly impacted the banking sector worldwide. SA’s advanced banking system has adapted to changes efficiently in some sectors, while it falls short in others. Martin (2019) states that while the 4IR gives rise to opportunities in convenience and efficiency, it also presents a challenge especially in the domains of data security, hacking, consumer protection, and laws regarding technology use, innovation, and implementation. According to Thwaits (2016), and Slazus and Bick (2022), financial technology is massive and growing within SA. While financial technology has seen continuous growth in SA, digital banking promotes ease of use but has suffered from fears of fraud and safety. The SA Reserve Bank is also accountable for promoting the reliability of local banking, through the effective application of relevant regulatory and supervisory standards and the minimising of systemic risk (Meiring, 2012). Objects 2 b and c of chapter one in the South African Electronic Communications and Transactions Act of 2002 (South Africa. Department of Communications, 2002) respectively state that the regulatory standards promote universal access, primarily in underserviced areas, and promote the understanding and acceptance of electronic transactions in SA.

4.2 Marketing Opportunities under Covid-19

The timeframe and effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are not well understood due to the nature of the virus. However, Khidhir (2020) states that once the COVID-19 pandemic and infection rates begin to slow down, customers will have already adapted to spending less time in banks due to digital adaption. This means that banks will need to focus on promoting and selling more products and services through digital channels to balance out the losses incurred in the reduction in sales previously acquired through traditional branch banking. Banks have taken the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to encourage the use of digital banking, emphasizing some of the benefits of digital banking, such as convenience due to 24/7 access, online funds management, and better rates. However, due to low smartphone use among older residents in some areas (South Africa. StatsSA, 2016), selected in-branch services are still required by a large sector of the population, particularly by elderly clients who cannot efficiently transition to digital channels in a short space of time. For instance, elderly clients, who are at high risk to contract COVID-19, are less likely to increase their use of online banking (Brennan, 2020). This is further discussed by Msweli and Mawela (2020), who state that elderly people are not comfortable with the use of digital technology and smartphones. Thus, if elderly clients have a limited understanding or knowledge of any type of digital technology, it is likely that they will be averse to using the products and services offered through that technology. They further state that elderly members of the community are a signi?cant business opportunity for banks, and it may become an overlooked opportunity if the elderly’s needs are not taken into consideration. It thus becomes a vital opportunity for banks to attempt to draw clients, of all age groups, into the use of digital banking by accelerating the opportunities that have been presented by the national and international lockdown regulations.

4.3 Competition faced by South African Banks

South African Reserve Bank (2020) states that South Africa has 36 banks that operate through hundreds of branches. There are 33 commercial banks and 3 mutual banks. Of the 33 commercial banks (including the “Big Five” banks), 15 are registered banks and 18 are local branches of foreign banks. Studies that directly measure the degree of competitive behaviour usually find monopolistic competition in the South African banking sector (Moyo, 2018; Claessens and Laeven, 2004; Simbanegavi et al. 2015; and Simatele, 2015). Monopolistic competition is a type of imperfect competition, where many companies sell similar goods and services differentiated through branding and quality (Antoshchenkova and Bykadorov, 2014; Feenstra, 2016; OpenStax, 2016; Mieszkowska et al., 2022). Viljoen (1998) further states that monopolistic competition is a hybrid form of competition, since it establishes a fair amount of competition, but also contains elements of a monopoly.

In 2017, Camarate and Brinckmann (2017) mentioned three new digital banks, namely Discovery, Tyme and PostBank, which would bring in a new line of competition within the SA banking sector. Discovery, a brand that is already well developed in SA, aimed to make an impact in the digital banking landscape. Traditionally, banks and other financial institutions offer their products and services to individuals and existing businesses. However, the growth and success of digital technology has allowed these financial services providers to reshape and have more control over their value propositions, and venture beyond the scope of their traditional services into the banking market. The impact of these new digital banks has not been extensively analysed in past studies as their impact on the financial sector within South Africa is relatively recent. Fenwick and Edwards (2015) say that digital technology solutions have a significant impact within the businesses at organisational, national, and international levels. These new technologies collect data through continuous sensing from new, old, and existing clients. They process data through algorithms, which analyse data into patterns and then interpret these patterns to identify complications and suggest solutions. For instance, SAS (previously known as the Statistical Analysis System) state that financial institutions often regard consumer acquisition as a challenge in a highly competitive environment such as in the banking industry (SAS, 2015). Therefore, by collecting and analysing customer behaviour data, such as buying habits and preferences, financial institutions can identify a clear but complex picture of their consumers, allowing the institutions to personalize their products and services and develop new and innovative services. These ‘personalization’s’ help the institutions retain existing clients and the innovations offer opportunities to acquire new clients from younger generations such as Millennials and Generation Z (SAS, 2015).

4.4 Opportunities and Challenges in South African Digital Banking Sector

Opportunities are aspects or characteristics which can support or enable business establishments with links outside organisations (Namugenyi et al., 2019). Some opportunities present a threat for some companies, while others may find them favourable. In the SA banking industry, the threat of non-traditional banks (such as Discovery) entering the finance industry might be interpreted as an opportunity to gain market share. Existing banks, however, may regard this as a challenge as they now must face more competition, particularly in the digital banking sector.

Service quality is a vital component of digital banking. Definitions of the term service quality state that it is the product of an evaluation that consumers make between their expectations about a product or service and their individual perception of the way this product or service has been delivered (Parasuraman et al., 1994). Nxumalo (2017) states that service quality is important to achieve complete customer satisfaction. Economic conditions in SA are not always positive, as is shown by Islami et al. (2020) who show that companies are losing their ability to find methods that present opportunities to sustain existing success in the market, as well as to increase their market share and profit margins. A larger consumer base usually means larger public visibility, and consumers tend to choose the more visible companies over companies that are still establishing themselves.

To achieve a high market share, banks need to practice effective segmentation. This is confirmed in studies by Bach et al. (2013), Kabuoh (2017), and Aghaei (2021) who state that segmentation in banking is of high importance, as the practice of designing special products and services for identifiable groups of clients is at the core of the modern approach to banking.

Creative distribution and innovation also allow SA banks the opportunity to stand out from their competitors. Al-Salaymeh (2013) states that new goods and services in banking are an indication of creativity implementation by banks, which include digital banking. This is contrasted in studies by Munusamy et al. (2012),Ramyah et al. (2006), and Gharbi and Kammoun (2022), who state that in order for internet banking to take off, one of the vital factors will be internet access. This is because a customer will not be able to use digital banking if they do not have some form of Internet connectivity. Despite the service being promoted extensively, it will remain unused unless clients have access to the Internet.

4.5. Personalization and Safety of Banking

Consumer perception refers to the ways in which consumers form distinct opinions and feelings about companies, and the products or services they offer through different channels. In this process, consumers select, categorize, and interpret data about these products or services to inform themselves with a clear view of the product or service offered to them. Tong et al. (2012) state that due to the increasing popularity and availability of smartphones, companies are now able to provide new products and services to customers. Through the implantation and offering of these services, IT has made one-to-one marketing in banking a reality, with links to targeted clients on a personal level. Consumer Perception Theory, adapted by Adefulu and Van Scheers (2016), explain consumer behaviour and perception by analysing reasons for buying or not buying a product or service. In self-perception, consumers individually analyse various interrelated criteria. This is discussed by Agyekum et al. (2015), who state that consumers use different variables to determine the quality of a product or service. These qualities are dependent on the individual consumer in question. For instance, in digital banking, some consumers may use Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) payment methods more comfortably and efficiently, whereas other consumers may prefer going directly to a bank to process these payments. In other instances, consumers may feel that their monetary transactions are too important to trust to digital banking channels, particularly because it is a new service in comparison to traditional branch banking. Previous studies, such as by Talke and O’Connor (2011), discuss the impact of these new services on consumer perception, but their study uses expert views, rather than collecting the data from the actual customer. Also, past studies such as by Yee and Yazdanifard (2014) and Kazmi (2012), analyse how perception influences buying behaviour on a digital and non-digital level, but fail to incorporate detailed information pertaining to how a consumer’s self-perception can influence the use of digital services. Secondly, price perception, and more particularly from the customer’s point of view, is frequently used as an indicator of the expectations of the product or service offered (Mattila and O’Neill, 2003; Han and Ryu, 2009). This is further discussed by Banyte et al. (2016) who states that the process of price perception is indirect and dependent on the perceiver’s expectations, previous knowledge, generated information, and stimuli.

5. Constructs of Digital Banking

Digital banking involves a wide range of interconnected services that require several variables to deliver the service to consumers. These services have different consumer perceptions, and impact digital banking in difference ways.

5.1 Perceived Value

Service as a product represents an extensive range of intangible services from both for-profit and non-profit agencies (Jones and Shandiz, 2015). The term ‘value’ refers to the relative worth, merit, or importance of a product or service. In marketing it is referred to as ’market value’ which is the capacity of services or products to satisfy a purchaser’s needs and wants (Brijball and Lombard, 2012). The concept of market value is further analysed into a value metrics process as follows:

Consumer acquisition. Measures the rate at which the organization attracts new customers. With relation to key success factors for digital personal banking, banks need to acquire new clients on a consistent basis. Capitec Bank has recorded a large number of client acquisition in the past five years, more than any of the other top four SA banks (Khumalo, 2019; BusinessTech, 2020). Marsigalia et al. (2014) states that the customer care experience is the most important part of a query and is vital in drawing in customers.

Consumer retention. Tracks the rate at which the organization retains ongoing relationships with the customers. Hamilton et al. (2017) suggests that adding new functions may increase charges, but it can increase sales as well, both through attracting new customers and maintaining current customers. There is, however, a contrast between presenting extra functions to attract customers and providing the proper functions to bring clients back.

Consumer satisfaction. Measures the satisfaction level of the consumers against the set performance criteria. Bell (2017) reveals that satisfied customers are more loyal, spend more with the company, and refer others, which increases the company’s consumer base.

Consumer profitability. Decision making based only on past values of clients can result in disappointing results. Many customers can have growth potential to become significantly more profitable over a period, while others can refer many new customers to the company (Cermak, 2015).

Yrjölä (2015) refers to customer value as value that is a subjective assessment of the positive and negative aspects of owning, or having the use of, a product or service. Customers often have a positive experience and opinion of a product or service if it not only meets and exceeds their expectations, but also offers some sort of pleasure. Such pleasure can come from the feeling of owning or being a client of a brand that has a positive and respected, or premium, brand image. If the organization can recognize what incentives lead their clients to customer satisfaction, they can have a greater likelihood of getting and holding clients. This is confirmed by one of the originators of service marketing and service quality, Parasuraman (1997), who stated that organizations that have a strong focus on customer value will develop a significant competitive advantage. For instance, all five of the “Big Five” banks in SA have, over time, developed powerful and well-respected brand images, and continue to use these positive images in providing customer value.

5.2 Purchase Intention

Purchase intention (PI), in the perspective of digital banking services, reflects the motivational influences that drive an individual to download the mobile banking application, provided free of charge by their bank, from smartphone App Stores. While this does require the user to have a stable internet connection and their own mobile data, there is no actual charge for downloading the application, i.e., there is no application fee. In that context, downloading the application can be viewed as an intention to use the application for conducting banking transactions any time anywhere on the move (Menon, 2019). The intent to then use the banking application is based on many differing factors that influence the individual decision.

Convenience. One of the core features that digital banking offers to clients is its convenience (Chitungo and Munongo, 2013; Dhanalakshmi, 2019). Clients can use close to a full line of banking services without having to visit a bank. Online banking offers banking simplification by saving consumers time and money by not having to travel to a branch or to process lengthy paperwork (Chigada and Hirschfelder, 2017; Mosteanu et al., 2020). It also allows consumers to make use of its services after retail banking hours and to independently open new accounts without extra charges. Different banks offer the same core digital banking services, such as making payments, checking balances and conducting transfers, but many banks attempt to offer other unique services or products in line with their brand to help in attracting customers. These unique offerings, however, need to stand out in order to keep customers satisfied, and prevent clients from changing their bank. For instance, Revathi (2019) says that digital banking benefits in a monopolistic competitive environment, as technological trends and changes in banking leads clients to change service provider for what they feel offers more convenience to them individually.

Practical quality. Durmaz and Efendioglu (2016) argue that digital advertising intends to serve clients as fast as could reasonably be expected and expects direction from clients as opposed to attempting to change their perception and feelings like in customary, traditional advertising. The practical ability to use internet banking, however, is not so easily achieved. It may take time for users to familiarize themselves with the application before they may decide to use it. This means that banks need to understand the process that their clients undergo when attempting access to digital banking.

6. Service Quality

6.1 Branch Service Quality

As banks and other companies continue to make use of technology advancements due to the 4IR, consumer-to-employee interaction has drastically decreased. This is due to technology outputs, which do not necessarily require an employee to carry out tasks and duties, as automated machines are able to provide the service at a significantly lesser cost. This, however, does have its drawbacks in terms of human and social interaction that customers often seek when shopping, and when banking especially. For instance, Uddin et al. (2014) state that employees interacting with clients can be positive for the company, as clients seek companies whose staff are attentive, speaking positively about the company and their services. Ultimately, the service quality received from the company forms a basis of how clients respond to the service received.

Consumer expectations have resulted in a major change in consumer behaviour. With customers now being more aware of products and services, as well as being monetary cautious, customers feel that the best companies should not only deliver excellent service but also provide value. Johnston and Kong (2011) agree that services consistently accompany an encounter and that such experiences give companies a chance to engage in emotional connections with customers.

There are significant ways in which a breach of privacy can impact digital banking. This includes the share of private and confidential information with third parties, fraud and hacking, and the incorrect recording of information like cell phone numbers, postal address and next of kin (Menon 2019). Bigne and Blesa (2003), Lee and Turban (2001) and Mbamba (2018) discuss the importance of trust in digital banking, noting that the nature of digital transactions are vastly different from those conducted through a bank’s branch.

6.2 Online Service Quality

Service characteristics are the vital components that make up much of the digital banking experience. Intangibility, Heterogeneity, Inseparability and Perishability are four categories of service characteristics that have been discussed by several authors (Moeller, 2010). Moon and Lee (2015), and He et al. (2022), argue that, even with quick innovative technological advances in online shopping, the significant drawback of e-shopping is that consumers cannot genuinely attempt to use a product or service before choosing to purchase it. Products that require higher rates of personal face-to-face interactions between customers and companies will show off more relational advantages to clients than services that require much less private or face-to-face interactions between clients and the company (Srihadia and Setiawan, 2015).

7. Conclusion

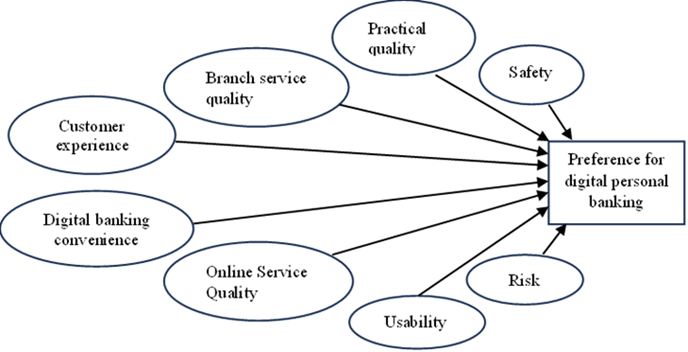

Based on the discussion above and the identification of the various issues that, according to the literature, may be key constructs to contributing to consumers preferring digital personal banking, the findings of this study can be summarised according to Figure 1.

Figure 1: Constructs possibly contributing to preference for digital personal banking

7.1 Contribution of this Study

The purpose of this article was to investigate, through a systematic review of extant literature, the digitization of banking in a developing nation, namely SA, to identify how digital banking is perceived by SA consumers and to identify what the key success factors are for successful implementation of such a banking digitization strategy. The nature of digital banking has been discussed in terms of the constructs of cashless transactions and e-commerce, the role of digital advertising, within the context of marketing and competition in the SA banking environment, and the opportunities and challenges present in this environment. The literature discussed in this paper highlights why it is necessary to gain a better understanding of banking digitisation and bank customers’ opinions about this. The literature provides some insight into banking consumers’ opinions about, and attitudes towards, digital banking, highlighting the key success factors of safety, accessibility, perceived value, convenience, and most important of all, service quality. Thus, this study has made two main contributions. First, it has set the scene for more, and deeper, research into the understanding of the factors that influence the use of digital personal banking, and second it has provided banking management with more objective and evidence-based knowledge about consumers’ perceptions about digital personal banking.

7.2 Managerial Implications

The banking industry in SA is very well developed, and all major banks have successfully introduced digital banking into their catalogue of services, as the literature shows. A major point of differentiation is that these banks attempt to offer a unique digital banking experience by incorporating a range of individual benefits and increasing ease of use. Although SA has one of the most industrialized economies in Africa (Naidoo, 2021), there exist substantial economic challenges and setbacks. One of the most prominent challenges the country faces is inequality. While companies race to keep up with digital technology, there is limited literature on the perceptions of consumers of, and the levels of their feelings about, the use of digital banking within SA. Furthermore, the literature has not adequately identified the effect of demographics and demographic inequalities on the adoption of digital banking, other than the obvious conclusion that older customers are more nervous in the use of technology and thus are more reluctant to adopt digital banking. And finally, little is known of the extent to which the SA consumer feels about safety, value, purchase intention, convenience, and quality of digital banking. This study has thus provided banking management with some knowledge about issues that may be critical to successfully marketing digital personal banking and provides guidance on possible factors that encourage consumers to prefer digital banking and thus might lead to a greater level of adoption by consumers.

7.3 Limitations

This study has not set out to be definitive and should be seen as more of an exploratory nature. Since there is so little published literature in SA on attitudes towards digital personal banking the findings should be considered as purely suggestive until they can be empirically tested. A further limitation is that the study population was delimited to a single geographic area in SA and so the findings should not be extrapolated to other areas of SA, or indeed to other developing economies. A final limitation is that since data was collected online, any opinions of those who are less digitally knowledgeable were not collected.

7.4 Recommendations for further research

Existing theory on digital banking needs to be extended by evaluating the constructs that contribute to the perception of digital banking, such as assessing the ease of use of digital banking, the convenience it provides, its safety, quality, and suitability for clients, as well as understanding the risks of, and preferences for, its use. Furthermore, by conducting research within a developing economy like SA, the impact of the current, unprecedented events such as the COVID-19 Pandemic can be considered, and how such events present opportunities and challenges to a developing country. A large portion of the banked and unbanked population do not use digital banking, and this could provide an opportunity for banks to concentrate on the informal business sector to service the currently underserved.

---

Author Contributions: Avikar Ramsundra: Conceptualization, Literature review, Data analysis and interpretation, Writing of original draft, Writing review and editing, Funding acquisition. Roger B. Mason: Conceptualization, Methodology development, Writing review and editing, Visualization, Supervision, Validation.

Funding:This research was partially funded by a Durban University of Technology post graduate bursary.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Achieng, M.S. and Malatji, M., 2022. Digital transformation of small and medium enterprises in sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 18(1), a1257. doi: 10.4102/td.v18i1.1257.

- Adamczewska-Chmiel, K. Dudzic, K. Chmiela, T. and Gorzkowska, A., 2022. Smartphones, the Epidemic of the 21st Century: A Possible Source of Addictions and Neuropsychiatric Consequences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), pp. 1-10.

doi:10.3390/ijerph19095152 - Adefulu, A. and Van Scheers, L., 2016. Consumer Perceptions of Banking Services: Factors for Bank’s Preference. Risk Governance & Control: Financial Markets & Institutions, 6(4), pp. 375-379. doi:10.22495/rcgv6i4c3art2.

- Aghaei, M., 2021. Market Segmentation in the Banking Industry Based on Customers’ Expected Benefits: A Study of Shahr Bank. Iranian Journal of Management Studies, 14(3), pp. 629-648. doi: 10.22059/IJMS.2021.305952.674132

- Agyekum, C.K., Haifeng, H. and Agyeiwaa, A., 2015. Consumer Perception of Product Quality. Microeconomics and Macroeconomics, 3(2), pp. 25-29. doi:10.5923/j.m2economics.20150302.01

- Ahmad, K. Arifuzzaman, M. Mamun, A. A. Oalid, J. M. K. B., 2021. Impact of consumer’s security, benefits and usefulness towards cashless transaction within Malaysian university student. Research in Business & Social Science, 10(2), pp. 238-250. doi:10.20525/ijrbs.v10i2.1065.

- Ajibade, P. and Mutula, S., 2020. Big data, 4IR and electronic banking and banking systems applications in South Africa and Nigeria. Banks and Bank Systems, 15(2), pp. 187-199. doi:10.21511/bbs.15(2).2020.17

- Al-Salaymeh, M., 2013. Creativity and Interactive Innovation in the Banking Sector and its Impact on the Degree of Customers’ Acceptance of the Services Provided. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 3(5), pp. 139-151.

- An, J., Do, D.K.X., Ngo, L.V. and Quan, T.H.M., 2018. Turning brand credibility into positive word-of-mouth: integrating the signalling and social identity perspectives. Journal of Brand Management, 26, pp. 157–175. doi:10.1057/s41262-018-0118-0

- Ananda, S., Devesh, S. and Lawati, A.M., 2020. What factors drive the adoption of digital banking? An empirical study from the perspective of Omani retail banking. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 25(1), pp. 14–24. doi:10.1057/s41264-020-00072-y.

- Antoshchenkova, I.V. and Bykadorov, I.A., 2014. Monopolistic Competition Model: The Impact of Technological Innovation on Equilibrium and Social Optimality. Automation and Remote Control, 78(3), pp. 537–556. doi:10.1134/S0005117917030134.

- Azeem, M.M., Ozari, C., Marsap, A., Arhab, S. and Jilani, A.H., 2015. Impact of E-Commerce on Organization Performance; Evidence from Banking Sector of Pakistan. International Research Journal of York University, 2(3), pp. 260-275. DOI:10.5539/ijef.v7n2p303

- Bach, M., Jukovic, S., Dumicic, S. and Sarlija, N., 2013. Business Client Segmentation in Banking Using Self-Organizing Maps. South East European Journal of Economics and Business, 8(2), pp. 32-41. DOI: 10.2478/jeb-2013-0007

- Banyte, J., Rutelione, A., Gadeikiene, A. and Belkeviciute, J., 2016. Expression of Irrationality in Consumer Behaviour: Aspect of Price Perception. Inzinerine Ekonomika-Engineering Economics, 27(3), pp. 334-344. doi:10.5755/j01.ee.27.3.14318.

- Beaven, M., 2014. Generational Differences in the Workplace: Thinking Outside the Boxes. Contemporary Journal of Anthropology and Sociology, 4(1), pp. 68-80.

- Bell, L., 2017. The Effects of Co-Creation and Satisfaction on Subjective Well-Being. (Master of Science in Hospitality and Tourism Management dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, USA.

- Bigne, E. and Blesa, A., 2003. Market orientation, trust, and satisfaction in dyadic relationships: A manufacturer-retailer analysis. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 31(11), pp. 574–590. doi: 10.1108/09590550310503302

- Brennan, H., 2020. Elderly forced to bank online in pandemic - but then cannot log on: The pandemic has accelerated the shift to online banking, but many are struggling to get to grips with it. The Telegraph, 11 October. [online] Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/personal-banking/current-accounts/elderly-forced-bank-online-pandemic-cannot-log/ [Accessed 3 July 2022].

- Brijball, S. and Lombard, M., 2012. Consumer Behaviour. Cape Town: Juta.

- BusinessTech., 2020. The best and worst banks in South Africa for customer satisfaction.. [online] Available at: https://businesstech.co.za/news/banking/382671/the-best-and-worst-banks-in-south-africa-for-customer-satisfaction/ [Accessed 22 July 2022].

- Camarate, J. and Brinckmann, S., 2017. A marketplace without boundaries, The future of banking: A South African perspective. Johannesburg: PwC South Africa.

- Carbonell, X., Oberst, U. and Beranuy, M., 2013. Chapter 91 - The Cell Phone in the Twenty-First Century: A Risk for Addiction or a Necessary Tool? In Miller, P. M. (Ed.) Principles of Addiction: Comprehensive Addictive Behaviors and Disorders, Volume 1. San Diego, CA: Elsevier.

- Cermak, P., 2015. Customer Profitability Analysis and Customer Lifetime Value Models: Portfolio Analysis. Procedia Economics and Finance, 25(2015), pp. 14-25. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00708-X

- Chigada, J.M. and Hirschfelder, B., 2017. Mobile banking in South Africa: A review and directions for future research. South African Journal of Information Management, 19(1), pp. 1-9. doi:10.4102/sajim.v19i1.789.

- Chitungo, S.K. and Munongo, S., 2013. Extending the Technology Acceptance Model to Mobile Banking Adoption in Rural Zimbabwe. Journal of Business Administration and Education, 3(1), pp. 51-79. doi:10.4236/ajibm.2014.42011.

- Claessens, S. and Laeven, L., 2004. What drives bank competition? Some international evidence. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 36(3), pp. 563-583. doi: 10.1353/mcb.2004.0044

- Clark, G.L. and Monk, A.H.B., 2017. Institutional investors in global markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Deora, M., 2018. A Study on Impact of Cashless Economy on Banking and Finance. International Journal of Advanced Research in Commerce, Management & Social Science, 1(1), pp. 28-36.

- Dhanalakshmi, P., 2019. A Study on Impact of Digital Banking in Madurai City. Journal of The Gujarat Research Society, 21(13), pp. 751-759.

- Durmaz, Y. and Edendioglu, I.H., 2016. Travel from Traditional Marketing to Digital Marketing. Global Journal of Management and Business Research: E Marketing, 16(2), pp. 35-40. doi:10.34257/GJMBREVOL22IS2PG35

- Ehrlich, A. and Elliott, M., 2019. The future of payments in South Africa Enabling financial inclusion in a converging world. September. Deloitte Africa. [online] Available at: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/za/Documents/risk/za-The-future-of-payments-in-South-Africa%20.pdf [Accessed 2 May 2022].

- Fabris, N., 2019. Cashless Society – The Future of Money or a Utopia? Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice, 8(1), pp. 53-66. doi:10.2478/jcbtp-2019-0003.

- Fatonah, S., Yulandari, A. and Wibowo, F.W., 2018. A Review of E-Payment System in E-Commerce. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1140(1), pp. 1-7. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1140/1/012033.

- Feenstra, R.C., 2016. Gains From Trade Under Monopolistic Competition. Pacific Economic Review, 21(1), pp. 35-44. doi: 10.1111/1468-0106.12150

- Fenwick, T. and Edwards, R., 2015. Exploring the impact of digital technologies on professional responsibilities and education. European Educational Research Journal, 15(1), pp. 117-131. doi:10.1177/1474904115608387.

- Gharbi, I. and Kammoun, A., 2022. Relationship Between Digital Banking and Financial Inclusion: Evidence from Tunisia. International Journal of Business Studies, 6(4), pp. 167-177. DOI: 10.32924/ijbs.v6i3.228

- Gleason, N.W. (ed.)., 2018. Higher Education in The Era of The Fourth Industrial Revolution. Singapore: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Hamilton, R.W., Rust, R.T. and Dev, C.S., 2017. Which features increase customer retention. MIT Sloan Management Review, 58(2), pp.79-84.

- Hammoud J., Bizri, R.M. and Baba, I.E., 2018. The Impact of E-Banking Service Quality on Customer Satisfaction: Evidence from the Lebanese Banking Sector. SAGE Open, 8(3), pp. 1-12. doi:10.1177/2158244018790633.

- Han, H. and Ryu, K., 2009. The Roles of The Physical Environment, Price Perception, And Customer Satisfaction in Determining Customer Loyalty in The Restaurant Industry. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 33(4), pp. 487-510. doi:10.1177/1096348009344212.

- Havasi, F., Meshkany, F.A. and Hashemi, R., 2013. E-Banking: Status, Implementation, Challenges, Opportunities. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 12(6), pp. 40-48. DOI: 10.9790/0837-1264048

- He, H., Zhou, G. and Zhao, S., 2022. Exploring E-Commerce Product Experience Based on Fusion Sentiment Analysis Method. IEEE Access, 10, pp. 110248-110260. DOI: 10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3214752

- Husain, A., 2017. Cashless Transaction Systems: A Study of Paradigm Shift in Indian Consumer Behaviour. PhD Management, Dayalbagh Educational Institute, Deemed University, India. [online] Available at: https://shodhgangotri.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/123456789/4546/1/synopsis.pdf [Accessed 2 May 2023].

- Islami, X., Musafa, N. and Latkovikj, M.T., 2020. Linking Porter’s generic strategies to firm performance. Future Business Journal, 6(3), pp. 1-15. doi:10.1186/s43093-020-0009-1.

- Jain, S., 2017. This Billionaire is Betting Big on Spending Power of Africa’s 1.2 Billion Consumers. 7 March. [online] Available at: https://frontera.net/news/africa/this-billionaire-is-betting-big-on-spending-power-of-africas-1-2-billion-consumers/ [Accessed 10 May 2022].

- Johnston, R. and Kong, X., 2011. The customer experience: a road‐map for improvement. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal. 21(1), pp. 5-24. doi:10.1108/09604521111100225

- Jones, J. and Shandiz, M., 2015. Service Quality Expectations: Exploring the Importance of SERVQUAL Dimensions from Different Non-profit Constituent Groups. Journal of Non-profit & Public Sector Marketing, 27(1), pp. 48-69. doi: 10.1080/10495142.2014.925762

- Jumba, J. and Wephukhulu, J.M., 2019. Effect of Cashless Payments on the Financial Performance of Supermarkets in Nairobi County. International Journal of Academic Research Business and Social Sciences, 9(3), pp. 1372–1397. doi:10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i3/5803.

- Kabuoh, M.N., 2017. Market Segmentation Strategy Based on Benefit Sought and Bank Customers' Retention in Selected Banks in Nigeria. International Journal of Innovative Research in Social Sciences & Strategic Management Techniques, 4(2), pp. 69-82.

- Kaur, P., 2019. Cash to Cashless Economy: Challenges & Opportunities. International Journal of 360 Management Review, 7(1), pp. 520-528.

- Kayembe, C. and Nel, D., 2019. Challenges and Opportunities for Education in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. African Journal of Public Affairs, 11(3), 79-94.

- Kazmi, S.P., 2012. Consumer Perception and Buying Decisions (The Pasta Study). International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, 1(6), pp. 1-10.

- Khan, A.G., 2016. Electronic Commerce: A Study on Benefits and Challenges in an Emerging Economy. Global Journal of Management and Business Research: B Economics and Commerce, 16(1), pp.19-21.

- Khan, J. and Craig-Lees, M., 2009. “Cashless” transactions: perceptions of money in mobile payments. International Business & Economics Review, 1(1), pp. 23-32.

- Khan, K.S., Kunz, R., Kleijnen, J. and Antes, G., 2003. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 96, pp. 118-121. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.3.118.

- Khando, K. Islam, M. S. and Gao, S., 2022. Factors Shaping the Cashless Payment Ecosystem: Understanding the Role of Participating Actors. In: A. Pucihar et al. (eds.), 35th Bled eConference, Digital Restructuring and Human (Re)action, Maribor, Slovenia. doi:10.18690/um.fov.4.2022

- Khidhir, A., 2020. Will COVID-19 reshape digital banking? Finextra (blog). [online] Available at: https://www.finextra.com/blogposting/18766/will-covid-19-reshape-digital-banking [Accessed 27 June 2023].

- Khumalo, K., 2019. Capitec gains 700000 clients in 2019. IOL Business Report, 29 March. [online] Available at: https://www.iol.co.za/business-report/economy/capitec-gains-700000-clients-in-2019-20203555 [Accessed 28 November 2022].

- Lauren, E. A., 2022. The Fourth Industrial Revolution in Banking Sector: Strategies To Keep Up With Financial Technology. SSRN, 13 September 2021, pp. 1-13. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4049913

- Lee, T.W. 1999. Using Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Lee, M.H., Yun, J.H.J., Pyka, A., Won, D.K., Kodama, F., Schiuma, G., Park, H., Jeon, J., Park, K.B., Jung, K.H., Yan, M-R., Lee, S.Y. and Zhao, X., 2018. How to Respond to the Fourth Industrial Revolution, or the Second Information Technology Revolution? Dynamic New Combinations between Technology, Market, and Society through Open Innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity - Open Access Journal, 4(3), pp. 1-24. doi:10.3390/joitmc4030021.

- Lee, M.K. and Turban, E., 2001. A trust model for consumer internet shopping. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 6(1), pp. 75–91. doi:10.1080/10864415.2001.11044227

- Linnes, C. and Metcalf, B., 2017. iGeneration and Their Acceptance of Technology. International Journal of Management & Information Systems, 21(2), pp. 11-26. doi:10.19030/ijmis.v21i2.10073

- Louw, C. and Nieuwenhuizen., 2020. Digitalisation strategies in a South African banking context: A consumer services analysis. South African Journal of Information Management, 22(1), pp. a1153. doi:10.4102/sajim.v22i1.1153.

- Majumder, K., 2015. A young researcher’s guide to a systematic review. Editage Insights, 29 April. [online] Available at: https://www.editage.com/insights/a-young-researchers-guide-to-a-systematic-review [Accessed 28 October 2022].

- Marnewick, C. and Bekker, G., 2022. Projectification within a developing country: The case of South Africa. Journal of Contemporary Management, 19(1), pp. 1-19. doi:10.35683/jcm21047.151

- Marsiglia, B., Evangelista, F., Celenza, D. and Palumbo, E., 2014. Web related companies' strategies for attracting new customers. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 3(1), pp. 1-10.

- Martin, A., 2019. We could be sleepwalking into a new crisis: How should the business world prepare? World Economic Forum, 16 January. [online] Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/how-can-businesses-prepare-for-the-biggest-global-risks-in-2019/ [Accessed 22 April 2023].

- Mattila, A.S. and O’Neill, J.W., 2003. Relationships between hotel room pricing, occupancy, and guest satisfaction: A longitudinal case of a midscale hotel in the United States. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 27(1), pp. 328-341. doi:10.1177/1096348003252361.

- Mbamba, C., 2018. Digital banking, customer experience and bank financial performance: UK customers' perceptions. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 36 (2), pp. 230-255. doi: 10.1108/IJBM-11-2016-0181

- McDonagh, M., Whiting, P., Bradley, M., Cooper, J., Sutton, A., Chestnutt, I., Misso, K., Wilson, P., Treasure, E. and Kleijnen, J., 2020. A Systematic Review of Public Water Fluoridation. CRD Report 18, NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York. [online] Available at: https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/crdreport18.pdf [Accessed 31 October 2022].

- Meiring, I., 2012. South Africa. Werksmans Attorneys, pp. 132-136. In Shapiro, D.E. (Ed.) Banking Regulation: In 27 jurisdictions worldwide. Getting the deal through. London: Law Business Research Ltd. [online] Available at: https://www.werksmans.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/safinal.pdf [Accessed 26 June 2023].

- Menon, B., 2019. Personal Trust, Institution Trust and Consumerism Attitudes towards Mobile Marketing and Banking Services in India. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 23(3), pp. 1-13.

- Mieszkowska, N., Kadale, R., Akter, K., Barsade, S.G., Sheridan, S., Sarker, A.R., et al., 2022. A Study on The Concept of Monopolistic Competition. Journal of Economic Research & Reviews, 2(2), pp. 192-194. doi: 10.33140/JERR.02.02.14

- Moeller, S., 2010. Characteristics of services – a new approach uncovers their value. Journal of Services Marketing, 24(5), pp. 359-368. DOI: 10.1108/08876041011060468

- Mohd, S. and Pal, R., 2020. Moving from Cash to Cashless: A Study of Consumer Perception towards Digital Transactions. PRAGATI: Journal of Indian Economy, 7(1), pp. 1-19. doi:10.17492/pragati.v7i1.195425.

- Moon, H. and Lee, H., 2015. The Effect of Intangibility on The Perceived Risk of Online Mass Customization: Utilitarian and Hedonic Perspectives. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 43(3), pp. 457-466. doi:10.2224/sbp.2015.43.3.457

- Mosteanu, N.R., Faccoa, A., Cavaliere, L.P.L. and Bhatia, S., 2020. Digital Technologies’ Implementation Within Financial and Banking System During Socio Distancing Restrictions – Back to The Future. International Journal of Advanced Research in Engineering and Technology, 11(6), pp. 307-315. DOI: 10.34218/IJARET.11.6.2020.027

- Moyo, B., 2018. An analysis of competition, efficiency, and soundness in the South African banking sector. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 21(1), pp. 1–14. doi:10.4102/sajems.v21i1.2291.

- Msweli, N.T. and Mawela, T., 2020. Enablers and Barriers for Mobile Commerce and Banking Services Among the Elderly in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review. In proceedings of 19th International Federation for Information Processing Conference on e-Business, e-Services, and e-Society, Skukuza, South Africa, April 6–8, pp. 319-330. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-45002-1_27.

- Mufingatun, M., Prijanto, B. and Dutt, H., 2020. Analysis of factors affecting adoption of mobile banking application in Indonesia: an application of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT2). Bisnis dan Manajemen, 12(2), pp. 88-106. doi:10.26740/bisma.v12n2.p88-105.

- Munusamy, J., Annamalah, S. and Chelliah, S., 2012. A Study of Users and Non-Users of Internet Banking in Malaysia. International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology, 3(4), pp. 452-458. doi: 10.7763/IJIMT.2012.V3.274

- Murugan, S., 2019. A Study on Consumer’s Awareness Towards Mobile Phone Usages in Chennai Environment. IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Business Management, 7(8), pp. 23-29. [online] Available at: https://www.impactjournals.us/archives/international-journals/international-journal-of-research-in-business-management?jname=78_2&year=2019&submit=Search&page=2 (Accessed 8 August 2023).

- Naidoo, P., 2021. South Africa’s Economy Is $37 Billion Bigger After Revision. Bloomberg, 25 August. [online] Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-08-25/africa-s-most-industrialized-economy-is-now-37-billion-bigger [Accessed 2 December 2022].

- Namugenyi, C., Nimmagadda, S.L. and Reiners, T., 2019. Design of a SWOT Analysis Model and its Evaluation in Diverse Digital Business Ecosystem Contexts. Procedia Computer Science, 159, pp. 1145-1154. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2019.09.283

- Ndayizgamiye, P., 2013. A Unified Approach Towards E-Commerce Adoption by SMMEs in South Africa. International Journal of Information Technology & Business Management, 16(1), 92-101.

- Ngandu, T.B., 2012. Perceptions of electronic banking among Congolese clients of South African Banks in the Greater Durban area. Master of Technology dissertation, Durban University of Technology, South Africa. [online] Available at: http://openscholar.dut.ac.za/bitstream/10321/949/1/NGANDU_2012.pdf [Accessed 4 April 2023].

- Nxumalo, T., 2017. The influence of service quality on the post-dining behavioural intentions of consumers at Cargo Hold, Ushaka Marine World. Master of Technology dissertation, Durban University of Technology, South Africa. [online] Available at: http://openscholar.dut.ac.za/bitstream/10321/949/1/nxumalo_2017.pdf [Accessed 4 April 2023].

- Ohene-Afoakwa, E. and Nyanhongo, S., 2017. Banking In Africa: Strategies and Systems for the Banking Industry to Win in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. BankSETA. [online] Available at: https://www.bankseta.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/BA3DD51-1.pdf [Accessed 2 December 2022].

- OpenStax., 2016. Principles of Economics. Huston, Texas: Rice University/OpenStax. [online] Available at: https://opentextbc.ca/principlesofeconomics/ [Accessed 4 October 2022].

- Ordu, M.M. and Anyanwaokoro, M., 2016. Cashless Economic Policy in Nigeria: A Performance Appraisal of The Banking Industry. Journal of Business and Management, 18(10), pp. 1-17. DOI: 10.9790/487X-1810030117

- Ouyang, S., 2022. Cashless Payment and Financial Inclusion. Journal of Financial Economics, August 8. Pp. 1-83. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3948925

- Parasuraman, A. 1997. Reflections on Gaining Competitive Advantage through Customer Value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25(1), pp. 154-161. doi:10.1007/BF02894351

- Parasuraman, A., Baker, J. and Grewal, D. 1994. The influence of store environment on quality inferences and store image. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(1), pp. 328-339. doi:10.1007/BF02894351

- Parma, R., 2018. A Study of Cashless System and Cashless Society: Its Advantages and Disadvantages. Indian Journal of Applied Research, 8(4), pp. 10-11.

- Raja, C., 2018. Cash to Cashless Economy- Importance and Impact. Worldwide Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development, 4(3), pp. 174-176.

- Ramavhona, T. and Mokwena, S., 2016. Factors influencing internet banking adoption in South African rural areas. South African Journal of Information Management, 18(2), 1-8. doi:10.4102/sajim.v18i2.642 .

- Ramdhani, A., Ramdhani, M.A., &, Amin, A.S. (2014). Writing a Literature Review Research Paper: A step-by-step approach. International Journal of Basic and Applied Science, 3(1), 47-56.

- Ramyah, T., Tahib, F. and Ling, K., 2006. Classifying Users and Non-users of Internet Banking in Northern Malaysia. Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce, 11(1), pp. 1-4. [online] Available at: https://www.icommercecentral.com/open-access/classifying-users-and-nonusers-of-internet-banking-in-northern-malaysia-1-13.pdf [Accessed 30 July 2023].

- Revathi, P., 2019. Digital Banking Challenges and Opportunities in India. EPRA International Journal of Economic and Business Review-Peer Reviewed Journal, 7(12), pp., 20-23. doi:10.36713/epra2985.

- Sankuratripati, S., Srivastava, J. and Shanbhag, D., 2006. Target Information Generation and Ad Server. Patent application. [online] Available at: https://patents.google.com/patent/US20070088821A1/en [Accessed 10 May 2023].

- SAS., 2015. Digital Banking and Analytics: Enhancing Customer Experience and Efficiency. [online] Available at: https://www.sas.com/content/dam/SAS/en_us/doc/whitepaper2/bai-digital-banking-analytics-107720.pdf [Accessed 6 July 2023].

- Shankaraiah, K. and Mahipal, D., 2021. Global Internet Users’ Growth and Top E-Commerce Markets. Chartered Secretary, 2 Research Corner, December, pp. 130-134.

- Simatele, M., 2015. Market structure and competition in the South African banking sector. International Institute for Social and Economics Sciences, 30, pp. 825-835.

- Simbanegavi, W., Greenberg J.B. and Gwatidzo, T., 2015. Testing for competition in the South African banking sector. Journal of African Economies, 24(3), pp. 303–324. doi:10.1093/jae/eju022

- Slazus, B. J. and Bick, G., 2022. Factors that Influence FinTech Adoption in South Africa: A Study of Consumer Behaviour towards Branchless Mobile Banking. Athens Journal of Business & Economics, 8(1) pp. 43-64. doi: 10.30958/ajbe.8-1-3.

- South Africa. Department of Communications., 2002. Electronic Communications & Transactions Act, 2002 (Act No. 25 of 2002). Government Gazette, 23708, 2 August. Cape Town: Government Printer. [online] Available at: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a25-02.pdf

- South Africa. StatsSA., 2016. Community Survey. Pretoria: Government Printer. [online] Available at: http://cs2016.statssa.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/NT-30-06-2016-RELEASE-for-CS-2016-_Statistical-releas_1-July-2016.pdf [Accessed 2 July 2023].

- South African Reserve Bank. (2020). Competition in South African Banking: An assessment using the Boone Indicator and Panzar–Rosse approaches. Pretoria: SARB. [online] Available at: https://www.resbank.co.za/Lists/News%20and%20Publications/Attachments/9819/WP%202002.pdf [Accessed 5 July 2023].

- Srihadi, T.F. and Setiawan, D., 2015. The Influence of Different Level of Service Characteristics and Personal Involvement towards Consumer Relational Response Behaviors. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 210, pp. 378-387. DOI: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.385

- Taher, G., 2021. E-Commerce: Advantages and Limitations. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting Finance and Management Sciences, 11(1), pp. 153-165. doi:10.6007/IJARAFMS/v11-i1/8987.

- Talke, K. and O’Connor, G., 2011. Conveying effective message content when launching new industrial products. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 28, pp. 943-956. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5885.2011.00852.x.

- Thwaits, C.R., 2016. The Barriers and Enablers to Effective Financial technology Start-up Collaboration with South African Banks. Master of Business Administration dissertation, University of Pretoria, South Africa. [online] Available at: https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/59788/Thwaits_Barriers_2017.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Accessed 28 February 2023].

- Tong, C., Wong, S.K. and Lui, K.P., 2012. The Influences of Service Personalization, Customer Satisfaction and Switching Costs on E-Loyalty. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 4(3), pp. 105-114. doi:10.5539/ijef.v4n3p105.

- Turner, A.R., 2013. Generation Z: Technology’s Potential Impact in Social Interest of Contemporary Youth. Master of Arts dissertation in Adlerian Counselling and Psychotherapy, Alder Graduate School, USA. [online] Available at: https://alfredadler.edu/sites/default/files/Anthony%20Turner%20MP%202013.pdf