Keywordsattachment theory celebrity worship Entertainment Industry fan support activities narcissism self-affirmation well-being

JEL Classification M31

Full Article

1. Introduction

In recent years, the phenomenon known as oshi-katsu (literally 'fan support activities for one's favourite celebrity or character') has grown rapidly in Japan (Bank of Japan, 2024, p. 4). The term oshi refers to 'a person or thing one admires so much that one wants to recommend it to others', while oshi-katsu refers to the activities undertaken to support that favourite (Hirose, 2023). These activities span a wide range of targets, including idols, anime or manga characters, video game characters, sports players or teams and even animals (Oshi ga 'ima iru', 2024). Although younger generations in Japan are often described as having lower consumer motivation compared to previous post-War generations, they display remarkable enthusiasm when it comes to spending for their favourite celebrities (Kubo, 2022). As a result, the phenomenon has drawn attention not only from businesses in the entertainment industry but also from academic researchers (Kubo, 2022). Surveys show that one in three Japanese people has a favourite celebrity or character, with women and younger individuals engaging in fan support activities more actively than men or older generations (Hakuhodo, 2024).

Fans often report that simply watching their favourite celebrity perform brings them joy, motivation and a sense of purpose (Hakuhodo, 2024; 'Oshi' towa?, 2023). Ishikawa and Yoshida (2022) noted that having such a favourite can directly enhance well-being. In Japanese culture, there is a value system that prioritizes 'being' (iru) over 'doing' (suru). Within this context, fan support activities are not necessarily about active participation; rather, simply being a fan and deriving satisfaction from that identity can itself promote happiness (Ishikawa and Yoshida, 2022). Thus, Japan's fandom activities are a form of consumer behaviour that not only generates significant profits for companies but also enhances the happiness of the fans themselves.

According to the Oshinomics report published by a major Japanese advertising company Hakuhodo (2024), Japan's fan support activities can be divided into two categories: official/direct activities (e.g. purchasing merchandise, joining official fan clubs, attending events) and fan-based/indirect activities (e.g. online interactions, fan art, information sharing). While indirect activities may not directly involve monetary spending, they play a crucial role in promoting celebrities and expanding fan communities.

However, some fans deliberately avoid interacting with others who support the same celebrity. This behaviour is known in Japan as dotan-kyohi (literally 'refusal to share') (Kondo, 2023). Such fans often show intense devotion to and invest heavily in their favourite celebrities, yet their exclusivity can disrupt fan communities and even lead to conflicts at live events (Kameyama, 2024). For businesses and celebrities alike, these fans represent both valuable customers and potential challenges. Understanding the psychology behind refusal to share is therefore essential, yet research on this topic remains limited.

2. Literature Review

Research on idol and celebrity worship has been conducted worldwide for decades. Earlier studies focused primarily on the types of individuals who tend to become deeply involved with celebrities (McCutcheon et al., 2016). Several studies have suggested that celebrity worshippers tend to be introverted and lack meaningful human relationships (Stever, 1995; Szymanski, 1977; Willis, 1972).

Celebrity Worship (CW) can be categorized into different levels, explained through the absorption-addiction model proposed by McCutcheon et al. (2002). CW ranges from the mildest to the most extreme level, as follows: the Entertainment-Social (ES) dimension, whereby individuals simply enjoy the content and information provided by celebrities; the Intense-Personal (IP) dimension, in which people start to fantasize about having a direct relationship with the celebrity; and the Borderline-Pathological (BP) dimension, wherein individuals excessively identify with the celebrity and may engage in obsessive or extreme behaviours (McCutcheon et al., 2002).

People psychologically immerse themselves in the lives of celebrities they encounter through the media and begin to fantasize about real-life relationships with them. This sense of involvement can develop further, leading to a desire for direct engagement with the celebrity. Higher levels of CW have been associated with poorer mental health (Maltby et al., 2004; Maltby et al., 2006) and lower levels of well-being (Maltby et al., 2001; McCutcheon et al., 2016). However, Mizukoshi (2024), who applied the CW scale to study fan support activities (Oshi-katsu), found results that differed from those of McCutcheon et al. (2016). Mizukoshi reported that individuals with higher levels of CW might actually experience increased self-affirmation and well-being compared to those with lower levels. In fact, those with lower levels of CW sometimes experience negative effects on self-affirmation and well-being from participating in fan support activities (Mizukoshi, 2024). Similarly, Harada et al. (2023) revealed that fans who devoted more time and money to fan support activities reported better health and greater self-affirmation than less involved fans.

Self-affirmation is defined as the evaluation of one's own attitudes as favourable or desirable from the perspective of both the self and others (Kawakoshi and Okada, 2015). It encompasses motivation, self-efficacy and a sense of fulfilment (Harada et al., 2023). Japanese people, particularly younger generations, are known to have lower levels of self-affirmation compared to other countries (Kawakoshi and Okada, 2015), yet fan support activities have been shown to enhance self-affirmation and even promote physical, mental and social well-being (Harada et al., 2023).

Furthermore, Takano and Okuno (2023), in their examination of enthusiasm for celebrities through the lens of romantic attachment, found that individuals' views on romance significantly influenced the development of romantic affection towards celebrities. People with positive attitudes towards romance are more likely to develop romantic attachments to celebrities. Conversely, those struggling with interpersonal relationships tend to show intense support for celebrities, often regarding them as 'objects of passionate worship' due to difficulties in forming real-life relationships. In such cases, as Maltby et al. (2001) and McCutcheon et al. (2002) suggested, higher levels of CW tend to be associated with lower well-being. However, individuals with positive views of romance may experience greater well-being even at higher levels of CW because the romantic feelings themselves contribute to happiness (Takano and Okuno, 2023). These findings suggest that fan support activities in Japan fundamentally differ from celebrity worship in Western contexts.

The earliest research on refusal-to-share behaviour can be traced to Tsuji (2018), who explained this behaviour as a practice whereby fans deliberately avoid interacting with others who support the same idol to maintain an intimate, one-to-one connection. According to Tsuji (2018), this practice allows fans to optimize personal pleasure. In Japan, the keyword in the fan-idol relationship is 'familiarity'. The sense of familiarity increases when idols with limited charisma form groups rather than perform solo (Tsuji, 2018). Although this familiarity brings pleasure, the presence of other fans who support the same idol can interfere with this enjoyment. Consequently, some fans avoid 'same-fan overlap' by creating a private world shared only between themselves and the idol.

So, how do fans exhibiting refusal-to-share behaviour differ from other fans? Inoue and Ueda (2023) examined this question using the concept of psychological ownership, which comprises psychological unity and psychological responsibility. Their survey of idol fans revealed that fans with strong psychological unity identified themselves with their favourite idol and viewed other fans as allies, thereby fostering a sense of camaraderie. Conversely, fans with strong psychological responsibility believe that 'I alone understand and nurture the charm of my idol' and thus view other fans with hostility.

In terms of well-being, both fans with strong camaraderie and those displaying refusal-to-share behaviour exhibited high levels of well-being. However, camaraderie positively influenced the continuity of fan support activities, whereas exclusivity negatively influenced it (Inoue and Ueda, 2023).

While Huang, Lin, and Phau (2015) suggested that strong attachment to celebrities positively affects long-term loyalty towards human brands, refusal-to-share fans, despite their strong attachment, tend to lack long-term commitment. Inoue and Ueda (2023) proposed that such fans might support idols out of a sense of responsibility to 'raise' them before they become major stars, leading them to leave once the idol gains widespread popularity. However, not all refusal-to-share fans act out of responsibility. Masaki (2023) pointed out that fans may view their favourite idol as a child, a friend, or even a romantic partner, and that romantic fantasies about celebrities play a key role in CW.

Therefore, in its focus on the psychology of refusal-to-share behaviour in the context of Japanese fan support activities, this study asked the following research question:

RQ: What are the psychological characteristics of fans who display refusal-to-share behaviour in Japanese fan support activities?

While this phenomenon appears to be unique to Japan, some studies have linked fandom to the pathology of isolated excessive attachment (O'Neill et al., 2013, p. 4). This represents the toxic side of fandom (Zhao, 2022), which overlaps with refusal-to-share behaviour. The findings of this study could contribute to understanding and addressing toxic fan culture and excessive attachment, not only in Japan but also globally.

3. Methodology

This study adopted a qualitative approach to elucidate the psychology of fans who practice 'refusal to share'. Qualitative research describes the target phenomena and individuals' experiences in detail and interprets, in relation to context, participants' inner worlds (feelings, perceptions, beliefs, values, identities), the social relationships among participants and the processes preceding the phenomena (Imafuku, 2021). Most prior studies investigating the psychology of celebrity-worshipping fans have relied primarily on quantitative methods, such as surveys (e.g. McCutcheon et al., 2016; Mizukoshi, 2024), and have not sufficiently explored the inner experiences of fans. Because this study focuses on an under-researched subgroup-fans who exhibit refusal-to-share behaviours towards fellow supporters-we considered hypothesis-testing designs inappropriate and instead employed a qualitative approach.

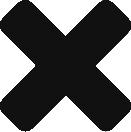

We conducted semi-structured interviews with 21 self-identified fans who practiced this refusal-to-share behaviour in relation to idols, YouTubers, voice actors, and manga/anime characters. Participants were recruited through outreach to university students in Tokyo and via snowball sampling. The interviews were conducted online using Zoom, with each lasting approximately 60 to 90 minutes. Table 1 presents the participants' attributes and favourite celebrities. All participants were women aged 19 to 33 years. This gender composition reflects both the greater prevalence of fan support activities (oshi-katsu) among women compared with men (Hakuhodo, 2024) and the historical origins of refusal-to-share behaviour in female fandom surrounding Japanese male idol groups, where such sentiments have been particularly pronounced (Tsuji, 2018). When participants had more than one favourite celebrity, they were asked to list all of them; the numbers in parentheses in Table 1 indicate multiple favourites.

All interview data were transcribed verbatim. Two authors independently performed open coding on the transcripts (Saiki-Craighill, 2016), repeatedly refining the codes until theoretical saturation was reached. Through extensive discussion, they finalized the labels and themes and organized the concepts. To ensure reliability and validity, we employed triangulation by conducting member checks with interviewees when necessary and by obtaining an external audit by a researcher not directly involved in the study.

Table 1. List of Interviewees

Source: Primary data

4. Results

Previous studies on refusal to share tended to treat all such fans as a single homogeneous group. However, analysis of the data obtained in this study's interviews revealed several distinct types of fans who refuse to share their favourites with other fans.

Focusing on the concept of romantic attachments-a core notion in CW (McCutcheon et al., 2016; Takano and Okuno, 2023)-this study first divided fans who practiced refusal to share into two orientations: romantic and non-romantic. Further, based on the data analysis, the concept of self-affirmation, highlighted by Harada et al. (2023), emerged as a key factor. Within each orientation, fans were then classified as either high self-affirmation-those who view their refusal-to-share behaviour positively-or low self-affirmation-those who experience inner conflict over their refusal-to-share behaviour.

Ultimately, four types were identified:

1. Romantic / High Self-Affirmation

2. Romantic / Low Self-Affirmation

3. Non-Romantic / High Self-Affirmation

4. Non-Romantic / Low Self-Affirmation

The following sections describe each type in detail.

Romantic / High Self-Affirmation

This type harbours romantic feelings towards celebrities and frequently fantasizes about dating or marrying them. In McCutcheon et al.'s (2002) classification of CW, this group aligns with the Intense-Personal (IP) or Borderline-Pathological (BP) dimension. As Takano and Okuno (2023) noted, they hold positive attitudes towards romance and strongly desire marriage and happiness, yet they cannot fulfill this desire in real life, leading them to indulge in fantasies about celebrities:

I just want to be in love... how should I put this? For me, marriage means living a peaceful and happy life, and I want to share that with him [the celebrity I like]. That's why I want to marry him. (#2)

Because they view celebrities as romantic partners, jealousy fuels strong possessiveness, causing them to see all other fans as rivals:

When I see my favourite celebrity giving romantic-looking fan service to other fans, I can't stand it. It's hard to explain, but if you want to marry someone-even just in your heart-you don't want to see them doing that with someone else. During concerts, when it's fan service time, I just don't want to see anything except what's directed at me. If they give attention to someone nearby and don't notice me, it really hurts. (#15)

This type positively interprets their refusal-to-share behaviour as natural, given their romantic attachment: 'I'm seriously in love. But only one person can marry him in this world. It's a competition' (#4).

They acknowledge that refusal to share might generate negative feelings among others but feel no need to stop because, for them, happiness lies in romantic exclusivity:

I understand people might think, "Is she weird?" when they hear about refusal-to-share behaviour. So I don't go around announcing it. But if I want to cherish my feelings, I need to stick to my approach. I have no intention of stopping. (#17)

It doesn't really cause me any problems, so I've never thought about quitting. It's for my own sake. Without it, things would get messy. (#21)

For fans of fictional characters, the rejection of other fans tends to be even stronger than for fans of real-life celebrities. Fictional characters allow greater space for personal imagination, which may explain why Japanese fan culture is rich in fan fiction (Kubo, 2019). These fans dislike even the fantasies of other fans and want to preserve a world shared only between themselves and the character: 'To keep dreaming happily, I want to imagine a world without others' (#8).

This type experiences no dissatisfaction with their fan support activities' environment and achieves what Tsuji (2018) termed the 'optimization of personal pleasure'. They also show little interest in sharing their fan experiences with others, preferring self-contained enjoyment.

Romantic / Low Self-Affirmation

People with low self-affirmation often harbour self-dislike and attribute negative experiences and emotions to themselves (Mizuma, 1996). This type, while romantically attached to celebrities, feels self-hatred over their refusal-to-share tendencies and wishes to stop. Like the high self-affirmation romantic type, they long for love and happiness, yet they also recognize that real relationships with celebrities are unattainable. They know that healthy fandom involves shared excitement within a community, but cannot overcome their rejection tendencies, thus creating inner conflict: 'I really want to overcome my refusal-to-share behaviour. I feel like I'm strangling myself and could live more freely without it. But I probably never will' (#7).

They envy fans who can enjoy communal fandom and wish they could return to a lighter, Entertainment-Social (ES) dimension of CW but feel stuck due to self-negativity and age: 'I wanted to quit refusal-to-share behaviour and have a happy fandom life, but now that I'm 23, I know it's impossible' (#8).

This type often experiences inferiority when comparing themselves with other fans-particularly those who are more enthusiastic or attractive-which leads them to refusal-to-share behaviour as a kind of escape: 'There are so many glamorous fans. I feel like I can't win against them... like they're the real heroines, and it makes it hard to keep dreaming' (#8).

Despite fandom's potential positive effects on well-being (Ishikawa and Yoshida, 2022; Mizukoshi, 2024), these fans struggle to feel fully happy because of self-loathing tied to their refusal-to-share behaviour.

Non-Romantic / High Self-Affirmation

The two non-romantic types lack romantic attachments to celebrities and do not view them as potential partners. Their refusal-to-share behaviour serves purely to maximize personal comfort-again echoing Tsuji's (2018) 'optimization of personal pleasure'. Unlike romantic types, who act out of jealousy, non-romantic types often reject fellow fans because they resent other fans for misinterpreting or oversimplifying the celebrity's personality: 'I appreciate that people like the same celebrity, but I don't want them talking about him carelessly' (#10).

They believe that they understand the celebrity best. As Tokuda (2010) noted, fans without romantic feelings recognize that idols exist within a fictionalized realm and knowingly support them without romantic delusion. They simply want to be the primary interpreter of the celebrity's persona and, with high self-affirmation, feel confident in that role: 'When someone less passionate than me claims to be a fan, I just think, "You don't really get it''' (#10).

Many in this group have practiced refusal to share for over five years; they are satisfied with the comfortable environment it provides and have no desire to stop.

Non-Romantic / Low Self-Affirmation

Like the previous type, this group lacks romantic attachment and wants to be the main interpreter of the celebrity's persona. However, they lack confidence in their understanding and compare themselves unfavourably with other fans, leading to refusal-to-share behaviour as an escape from feelings of inadequacy: 'I just don't want to get hurt. When I compare myself to others, I get depressed... so I avoid it' (#3).

Their low self-affirmation makes them prone to self-hatred towards both their fandom life and their refusal-to-share behaviour. While they want to support the celebrity wholeheartedly, they wish they could accept fan interactions more positively: 'I want to quit refusal-to-share behaviour because my idol works so hard. They put effort into fan interactions, so I want to appreciate that, rather than reject it' (#11).

Yet, they cannot quit because other fans' behaviour often feels 'uncomfortable': 'I don't want to monopolize the celebrity, but other fans just feel gross to me. Still, without them, I couldn't get certain information, so I can't completely avoid them. It just feels uncomfortable' (#11).

This discomfort may reflect their low self-affirmation. As Mizuma (1996) noted, people with low self-affirmation sometimes project negative feelings onto themselves, possibly seeing unpleasant traits in other fans as reflections of themselves.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

The underlying psychology of fans who refuse to share

Based on the results of the interview survey, this study identified four distinct types of fans who reject fellow-fans' engagement: Romantic / High Self-Affirmation, Romantic / Low Self-Affirmation, Non-Romantic / High Self-Affirmation, and Non-Romantic / Low Self-Affirmation. While each type displays unique tendencies, a common feature across all groups is that rejecting other fans provides them with a certain sense of 'comfort'. In other words, other fans represent a source of 'discomfort', and fans either exclude or distance themselves from such individuals to maintain an emotionally secure environment. At the root of this strong sense of self-protection lies a desire to safeguard oneself and one's inner world.

This form of self-directed affection can be described as narcissism, generally understood as love and care for the self (Nakamura, 2004). The defensive consciousness arising from narcissism consists of a number of defence mechanisms called narcissistic defences, which refer to the processes of preserving one's idealized aspects while denying their limitations. Regardless of romantic orientation or self-affirmation level, refusal-to-share fans appear to employ such 'narcissistic defences' to protect their 'dream world'. This interpretation is reinforced by the fact that all interviewees in this study cited 'self-protection' as their primary reason for rejecting other fans.

At the same time, many interviewees expressed feelings of possessiveness. While often discussed in the context of romantic relationships, possessiveness can also arise in non-romantic contexts, such as parent-child relationships, or even in relation to time, space or objects (Evart-Chmielniski, 1955/2017). In romantic settings, women with stronger narcissistic tendencies tend to display greater possessiveness and jealousy (Oshio, 2000). Refusal-to-share fans idealize their relationship with the celebrity and attempt to exclude or avoid any individuals who might threaten this 'ideal relationship', thereby giving rise to other fan rejection behaviours.

Research has shown that highly narcissistic individuals, particularly women, seek a sense of oneness in romantic relationships through possessiveness (Oshio, 2000). In the context of fandom, this implies a desire to merge identities with the celebrity, in which the fan imagines that the celebrity shares the same emotions and feelings as themselves. Such tendencies were especially pronounced among the Romantic / High Self-Affirmation and Romantic / Low Self-Affirmation types. Within their 'dream worlds', celebrities function as romantic partners-or potential partners-who act according to the fans' expectations. Other fans thus represent a potential rival who might 'steal' the beloved celebrity away.

For fans with high self-affirmation, marriage to the celebrity is envisioned as an achievable dream, making other fans clear romantic rivals. Conversely, fans with low self-affirmation yearn for emotional oneness with the celebrity, while simultaneously recognizing the impossibility of an actual romantic relationship. In many cases, fandom itself serves as a means of escaping from reality (Hakuhodo, 2024). Yet, the awareness that, for the celebrity, they remain just one among many fans renders reality unbearable. From this perspective, other fans symbolize the intrusion of reality into their fantasy world, with other-fan rejection emerging as a psychological defence against this intrusion.

While Inoue and Ueda (2023) argue that psychological oneness fosters solidarity among fans, such solidarity arises when oneness develops from collective psychological ownership. For refusal-to-share fans, however, psychological ownership is individualized and sought exclusively within the one-on-one relationship between fan and celebrity rather than shared with fellow fans.

Possessiveness rooted in narcissism can also give rise to a sense of responsibility (Evart-Chmielniski, 1955/2018). Although this sense of responsibility is often observed in romantic relationships, in this study it was particularly salient among the two Non-Romantic types. Fans who experience psychological responsibility in fandom wish to 'nurture' their favourite celebrity and contribute to their success, believing themselves capable of doing so (Inoue and Ueda, 2023).

As noted earlier, non-romantic fans do not fantasize about marriage to the celebrity; rather, they view themselves as the celebrity's closest-or most devoted-supporters. When other fans discuss the celebrity's behaviour without proper understanding or act in ways that might displease the celebrity, these fans feel irritation or even anger. To avoid such negative emotions, they exclude or distance themselves from other fans.

Inoue and Ueda (2023) suggest that fans who feel psychological responsibility perceive other fans as competitors because they view themselves as the ones who will guide the celebrity to success. However, the findings from this study indicate that this tendency appears primarily among fans with high self-affirmation. Confident in their own abilities, they believe they understand the celebrity better than anyone else. In contrast, fans with low self-affirmation lack confidence in their understanding or ability to nurture the celebrity. For them, the belief that 'only I truly understand and can nurture the celebrity' exists solely within their dream world. Consequently, other-fan rejection may serve as a self-defensive mechanism to protect this fragile fantasy from being shattered.

Both the sense of oneness and the sense of responsibility arising from possessiveness appear to heighten self-protective consciousness. The stronger these feelings, the more likely fans are to avoid interacting with fans who share the same favourite. Some low-self-affirmation interviewees even expressed self-loathing towards themselves for shunning fellow fans with the same bias. Nonetheless, they could not abandon the practice precisely because of the strength of their desire for oneness or responsibility. It is possible that if these desires weaken over time, some fans may eventually stop avoiding same-favourite fans.

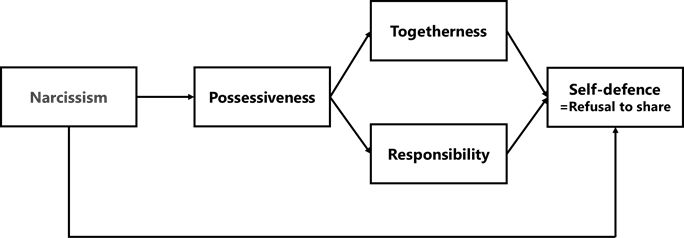

Interestingly, a few interviewees stated explicitly that they felt 'no possessiveness'. In such cases, self-protection seems to emerge directly from narcissism, rather than being mediated by possessiveness. If so, the stronger the narcissism, the stronger the self-protective consciousness is likely to become. Based on these findings, the mechanism through which narcissism leads to avoiding same-favourite fans can be conceptualized, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. How refusal to share arises from narcissism

Source: Primary data

Theoretical interpretation

The four fan types identified in this study can be linked to the principal components of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI) developed by Raskin and Hall (1979). These components consist of seven dimensions: Authority, Exhibitionism, Superiority, Vanity, Exploitativeness, Entitlement and Self-Sufficiency (Raskin and Terry, 1988).

For example, the Non-Romantic / High Self-Affirmation type often believes they 'understand the celebrity better than anyone else'. This reflects both a desire to assert superiority over others and confidence in the correctness of their own judgment. Such attitudes can be explained by the NPI components of Authority and Superiority. The self-contained sense of superiority reflected in statements such as 'Other fans don't truly understand him/her' also aligns with Self-Sufficiency and Superiority. Similarly, the Romantic / High Self-Affirmation type's belief that 'the celebrity is my partner or future spouse' may be related to the Entitlement and Vanity dimensions.

Conversely, refusal-to-share with low self-affirmation exhibit narcissism but are highly sensitive to criticism and comparison and lack the inner strength to consistently assert their desires. This tendency overlaps with the concept of vulnerable narcissism identified in previous research (Wink, 1991). Individuals high in vulnerable narcissism tend to be anxious, introverted and lacking in self-confidence (Mahadevan, 2024). In contrast, the narcissism of high self-affirmation refusal-to-share fans aligns more closely with grandiose narcissism (Mahadevan, 2024), which is characterized by superiority, arrogance, and confidence (Miller and Campbell, 2008).

Moreover, the four refusal-to-share types proposed in this study can also be interpreted through the lens of Attachment Theory, originally proposed by John Bowlby (1907-1990). Mary Ainsworth (1913-1999), a key researcher in attachment theory, classified patterns of close relational behaviour into three types: secure, avoidant and anxious (Ainsworth et al., 1970, 1978). While the Romantic / High Self-Affirmation type in this study can be described as secure in the sense that they express confidence in their relationship with the celebrity, they also exhibit avoidant tendencies through their deliberate exclusion of other fans. The other three types can likewise be mapped onto the attachment patterns identified in attachment theory. Table 2 summarizes these associations, along with interpretative notes.

Table 2. Types of refusal to share and attachment patterns

| Type | Attachment Pattern | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Romantic / High Self-Affirmation | Secure ? Slightly Avoidant | Confident in relationship with the celebrity; strategically excludes others |

| Romantic / Low Self-Affirmation | Anxious-Preoccupied | Highly anxious about losing the celebrity; hypersensitive to same-favourite fans yet self-critical |

| Non-Romantic / High Self-Affirmation | Dismissive-Avoidant | Rejects shared experiences with others; maintains distance to protect private world |

| Non-Romantic / Low Self-Affirmation | Fearful-Avoidant | Avoids others while feeling anxiety and inferiority about relationship with celebrity |

Source: Primary data

Continuity of fandom

It has been noted that refusal-to-share fans tend to have low continuity in their fan activities (Inoue and Ueda, 2023). Among the participants in this study, some interviewees reported that they stopped being fans when their favourite idols began dating or got married:

Until around the time I graduated from high school, I was deeply into a serious romantic phase, but after graduation, that feeling suddenly faded. I also used to be an extreme fan who avoided others who liked the same favourite, but that, too, eventually disappeared. Then, when I got really busy with university, news broke about his romantic relationship. Because the first dating report came out right when my passion was already cooling down, it felt like something inside me just snapped, and I was like, "That's it, I'm done." And I really did quit right then. (#20)

This interviewee likely exhibited strong refusal-to-share behaviour stemming from intense possessiveness and psychological oneness born from a romantic orientation. However, as her passion gradually cooled, her refusal-to-share behaviour diminished, and when confronted with the reality of the idol's romantic relationship, she seemed to have completely lost the dream. As repeatedly emphasized, the essential aspect of fan activities is the ability to 'keep dreaming'. Refusal to share serves as a form of self-defence to preserve the dream and prevent it from being shattered by other fans. Yet, when the celebrity themselves destroys that dream, there is no way to prevent it. For those with strong narcissism, choosing to cut ties with the celebrity in order to protect themselves is a natural outcome.

Similarly, there appear to be instances where non-romantic-oriented fans suddenly lose interest and withdraw once the 'star-in-the-making' they supported actually becomes popular:

Honestly, I think this happens to almost everyone who supports juniors [trainees or aspiring stars]. After they debut, suddenly a lot of people become fans, and at that moment, I just felt like, "Well, now they've made it big, so I'm done" (#9).

Non-romantic-oriented fans often feel a sense of responsibility towards the celebrity, believing they are the ones raising and shaping the star into someone popular. In other words, the notion of 'I am the one who makes them a star' itself constitutes their 'dream world'. When the idol actually becomes a star, it signifies the end of that dream world. It is unsurprising that refusal-to-share fans with strong narcissistic tendencies would choose to distance themselves in order to protect their own world.

The above findings reveal that refusal-to-share interviewees do, indeed, sometimes withdraw from fan activities. However, whether this is exclusive to refusal-to-share fans remains unclear, since even fans who engage in fan support activities harmoniously with others may withdraw due to changes such as an idol's marriage or the success of a young, up-and-coming star. Nevertheless, it is possible that refusal-to-share fans with strong narcissistic tendencies who cherish their dream world are less able to tolerate situations that shatter those dreams. Highly narcissistic individuals are often sensitive to external stimuli and easily hurt, leading them to adopt self-protective behaviours (Watanabe, 2011).

Limitations and future research

This study conducted interviews with 21 women who self-identified as fans who refuse to share (dotan-kyohi) in Japanese fan activity (oshi-katsu) communities in order to clarify the characteristics of such fans. Based on the results, we classified these individuals into four types and derived a mechanism for how refusal-to-share behaviour emerges. However, whether this hypothesis is correct should be tested through future quantitative research. The NPI would likely serve as an appropriate measurement scale.

Moreover, previous studies (Hakuhodo, 2024) have pointed out that many people who engage in refusal-to-share behaviour in fan support communities are young women, while other studies (Weidmann et al., 2023) have shown that men tend to score higher than women on narcissism. Future research should therefore focus on and conduct interviews with men as well.

Narcissism can be divided into healthy narcissism, or self-love, and unhealthy narcissism (Nakamura, 2004). However, the present study was not able to address the issue of whether the narcissism observed was healthy or unhealthy. When narcissism progresses in an unhealthy direction, it is often treated as a personality disorder (e.g. Broucek, 1982; Masterson, 1981, 1993; Rosenfeld, 1993). The 'Borderline-Pathological (BP)' dimension of CW classified by McCutcheon et al. (2002) may in fact correspond to individuals whose narcissism has reached the very borderline of pathology. Focusing on the healthiness of narcissism and investigating the kinds of narcissism that refusal-to-share individuals actually exhibit would make for an intriguing line of research. Such findings could provide insights into the ways in which celebrities should interact with refusal-to-share fans to manage communities smoothly and without conflict.

---

Author Contributions: Miyuki Morikawa: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing - Original Draft. Mayu Amano: Methodology, Validation, Writing - Reviewing

Funding: This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest: The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest

Disclaimer / Publisher's Note

---

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note: The views, statements, opinions, data and information presented in all publications belong exclusively to the respective Author/s and Contributor/s, and not to Sprint Investify, the journal, and/or the editorial team. Hence, the publisher and editors disclaim responsibility for any harm and/or injury to individuals or property arising from the ideas, methodologies, propositions, instructions, or products mentioned in this content.

References

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., and Bell, S. M. 1970. Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development, 41(1), pp. 49–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/1127388

- Ainsworth, M. S., Blehar, M.C., Waters, E. and Wall, S. 1978. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Bank of Japan, 2024. Chiiki Keizai Hokoku [Regional Economic Report]. Available online at: https://www.boj.or.jp/research/brp/rer/rer241007.htm (accessed 11 September 2025)

- Broucek, F. J. 1982. Shame and its relationship to early narcissistic developments. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 63(3), pp. 369–378.

- Evart-Chmielniski, E. 2017. L’exclusivisme personnel: Le personnalisme, son conditionnement (F. Kayo and Y. Kato, Trans.). The Japanese journal of psychological science, 38 (2), pp. 77–94. https://doi.org/10.20789/jraps.38.2_77 (Original work published 1955)

- Evart-Chmielniski, E. 2018. L’exclusivisme personnel: Le personnalisme, son conditionnement (F. Kayo and Y. Kato, Trans.). The Japanese journal of psychological science, 39(1), pp. 87–98. https://doi.org/10.20789/jraps.39.1_87 (Original work published 1955)

- Hakuhodo (2024). Oshinomics Report. Available online at: https://www.hakuhodo.co.jp/humanomics- studio/assets/pdf/OSHINOMICS_Report.pdf (accessed 11 September 2025)

- Harada, Y., Komatsu, Y., Kano, R. and Yoshimura, K. 2023. Influence of the act of supporting one’s favorite on one's well-being. Bulletin of the Faculty of Nursing and Human Nutrition, Yamaguchi Prefectural University, 16, pp. 1–6. https://www.l.yamaguchi-pu.ac.jp/archives/2023/01.part1/03.nursing%20and%20human%20nutrition/01.nursing_HARADA.pdf

- Hirose, R. 2023. Imadoki Oshikatsu jijo [The current state of oshikatsu]. Gekkan Kokumin Seikatsu [People's Life monthly magazine], 131, pp. 1–4. https://www.kokusen.go.jp/wko/pdf/wko-202307_01.pdf

- Huang, Y-A., Lin, C., and Phau, I. 2015. Idol attachment and human brand loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 49(7-8), pp. 1234–1255. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EJM-07-2012-0416

- Imafuku, R. 2021. Fundamental principles that you need to know when you undertake qualitative research. Japanese Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 5. https://doi.org/10.24489/jjphe.2020-002

- Inoue, A. and Ueda, Y. 2023. Effect of Psychological Ownership of Favorite Idols on Consciousness toward Other Fans and Well-Being. Japan Marketing Journal, 43(1), pp. 18–28. https://doi.org/10.7222/marketing.2023.034

- Ishikawa, Y. and Yoshida, H. 2022. Mukashi mukashi arutokoroni wellbeing ga arimashita [Once upon a time, there was a place called Wellbeing]. Tokyo: KADOKAWA.

- Kameyama, S. 2024. Hanzaikoi nimade hatten…Oshikatsu de ‘Dotankyohi’ wa tozen nanoka? [Escalating to criminal behaviour... Is it natural to reject fellow fans when pursuing your favourite idol?]. All About. Available online at: https://allabout.co.jp/gm/gc/506443/ (accessed 11 September 2025)

- Kawakoshi, M. and Okada, M. 2015. Factors Affecting Self-Affirmation of University Students. Journal of home economics of Japan, 66(5), pp. 222–233. https://doi.org/10.11428/jhej.66.222

- Kondo, E. 2023. Dotankyohi no kokoro [Mind of Dotankyohi]. Forum: a clinical psychology magazine, 16(1). pp. 14–15. https://ajcp.media/archives/3677

- Mahadevan, N. 2024. Conceptualizing grandiose and vulnerable narcissism as alternative status‐seeking strategies: Insights from hierometer theory. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 18(6), e12977. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12977

- Maltby, J., Day, L., McCutcheon, L. E., Gillett, R., Houran, J., and Ashe, D. D. 2004. Personality and coping: A context for examining celebrity worship and mental health. British Journal of Psychology, 95(4), pp. 411–428. https://doi.org/10.1348/0007126042369794

- Maltby, J., McCutcheon, L. E., Ashe, D. D., and Houran, J. 2001. The self-reported psychological well-being of celebrity-worshipers. North American Journal of Psychology, 3, pp. 441–452. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233858367_The_Self-Reported_Psychological_Well-Being_of_Celebrity_Worshippers

- Maltby, J., Day, L., McCutcheon, L. E., Houran, J., and Ashe, D. 2006. Extreme celebrity worship, fantasy proneness and dissociation: Developing the measurement and understanding of celebrity worship within a clinical personality context. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(2), pp. 273–283. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.paid.2005.07.004

- Masaki, D. 2023. The Psychology of ‘oshi’ : The relationship between my oshi and me. Contemporary Society Bulletin, Kyoto Women’s University, 17, pp. 53–62. https://doi.org/10.69181/3643

- Masterson, J.F. 1981. The narcissistic and borderline disorders: an integrative developmental approach. New York: Routledge.

- Masterson, J. F. 1993. The emerging self. A developmental, self, and object- relational approach to the treatment of the closet narcissistic disorder of the self. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

- McCutcheon, L. E., Lange, R., and Houran, J. 2002. Conceptualization and measurement of celebrity worship. British Journal of Psychology, 93, pp. 67–87. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1348/000712602162454

- McCutcheon, L. E., Ashe, D. D., Houran, J., and Maltby, J. 2003. A cognitive profile of individuals who tend to worship celebrities. The Journal of Psychology, 137(4), pp. 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980309600616

- McCutcheon, L., Browne, B. L., Rich, G. J., Britt, R., Jain, A., Ray, I., and Srivastava, S. 2016. Cultural differences between Indian and US college students on attitudes toward celebrities and the love attitudes scale. Journal of Studies in Social Sciences, 16(1), pp. 24–44. https://infinitypress.info/index.php/jsss/article/download/1457/621

- Mizukoshi, K. 2024. Oshikatsu ni okeru celebrity worship ga shohi kodo ni ataeru eikyo [The impact of young people's celebrity worship in their pursuit of their fandom on consumer behaviour]. Journal of research on social and economic life, 64(2), pp. 29–47. https://www.kokusen.go.jp/research/pdf/kk-202412_2.pdf

- Mizuma, R. 1996. The construction of self-disgust scale. Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology, 44, pp. 296–302. https://doi.org/10.5926/jjep1953.44.3_296

- Nakamura, A. 2004. Healthy Narcissism and Unhealthy Narcissism. Chiba University of Commerce Bulletin, 42(1), pp. 1–20. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/233918895.pdf

- Kubo, K. N. 2022. ‘Oshi’ no kagaku [The Science of ‘Oshi’]. Tokyo: Shueisha Shinsho.

- O'Neill, B., Gallego, J. I., and Zeller, F. 2013. New perspectives on audience activity: ‘prosumption’ and media activism as audience practices. In Niko Carpentier, K.C.S. and Hallett, L. (eds.). Audience Transformations: Shifting Audience Positions in Late Modernity. London: Routledge. https://arrow.tudublin.ie/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1025&context=cserbk

- Oshi ga ‘ima iru’ toiu hito ha yaku 6 wari, jakunen-so hodo takai keiko [Approximately 60% of respondents said they currently have a fave, with the percentage being higher among younger age groups]. 2024. Research note powered by LINE. Available online at: https://lineresearch-platform.blog.jp/archives/44545473.html (accessed 11 September 2025)

- Oshio, A. 2000. Narcissism and Relationships with the Opposite Sex in Adolescents. Bulletin of the Graduate School of Education and Human Development, Psychology and human developmental sciences, 47, pp. 103–116. https://doi.org/10.18999/nupsych.47.103

- ‘Oshi’ towa? ‘Fan’‘Suki’ tono chigai, kanrenyogo, sakuhin wo matomete kaisetsu! [What is ‘Oshi’? A comprehensive explanation of the differences between ‘fan’ and ‘like,’ related terms, and works!]. 2023. Domani. Available online at: https://domani.shogakukan.co.jp/878528 (accessed 11 September 2025)

- Raskin, R. and Hall, C. S. 1979. A narcissistic personality inventory. Psychological Reports, 45(2), p. 590. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.2466/pr0.1979.45.2.590

- Raskin, R., and Terry, H. 1988. A principal-components analysis of the narcissistic personality inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), pp. 890–902. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.54.5.890

- Rosenfeld, H. 1987. Impasse and Interpretation. London: Routledge.

- Saiki-Craighill, S. 2016. Grounded theory approach (Revised edition). Tokyo: Shinyosha.

- Shaw J.A. 1999. Sexual Aggression. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Stever, G. S. 1995. Gender by type interaction effects in mass media subcultures. Journal of Psychological Type, 32, pp. 3–22. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299423213_Gender_by_Type_Interaction_Effects_in_Mass_Media_Subcultures

- Szymanski, G. G. 1977. Celebrities and heroes as models of self-perception. Journal of the Association for the Study of Perception, 12, pp. 8–11.

- Takano, A. and Okuno, M. 2023. Gendai senen no taijinkanke no arikata ga oshi tono kanke-sei ni oyobosu eikyo [The impact of modern young people's interpersonal relationships on their relationships with idols]. Journal of Contemporary Behavioral Sciences, 39, pp. 41–50. https://iwate-u.repo.nii.ac.jp/record/2000179/files/cbsa-n39p41-50.pdf

- Tokuda, M. 2010. Johnny’s fan no shikou [The mindset of Johnny's fans]. Kunitachi Anthropological Research, 5, pp. 21–46. https://hermes-ir.lib.hit-u.ac.jp/hermes/ir/re/18563/kunitachi0000500210.pdf

- Tsuji, I. 2018. ‘Dotankyohi’ saiko: Idle to fan no kanke, fan community [Reconsidering ‘Dotankyohi’: The Relationship Between Idols and Fans, Fan Communities]. Japan sociologist, 3, pp. 34–49.

- Watanabe, T. 2011. The Effects of Mental Representations on the Relationship between Narcissistic Personality and Subjective Well-Being. Ritsumeikan journal of human sciences, 22, pp. 19–27. https://doi.org/10.34382/00004249

- Weidmann, R., Chopik, W. J., Ackerman, R. A., Allroggen, M., Bianchi, E. C., Brecheen, C., Campbell, W. K., Gerlach, T. M., Geukes, K., Grijalva, E., Grossmann, I., Hopwood, C. J., Hutteman, R., Konrath, S., Küfner, A. C. P., Leckelt, M., Miller, J. D., Penke, L., Pincus, A. L., Renner, K. H., …Back, M. D. 2023. Age and gender differences in narcissism: A comprehensive study across eight measures and over 250,000 participants. Journal of personality and social psychology, 124(6), pp. 1277–1298. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000463

- Willis, S. E. 1972. Falling in love with celebrities. Sexual Behavior, 2, pp. 2–8.

- Wink, P. 1991. Two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(4), pp. 590–597. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.61.4.590

- Zhao, Y. Q. G. 2022. Analysis of the Social Impact of Fandom Culture in ‘Idol’ Context. Advances in Journalism and Communication, 10, pp. 377–386. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajc.2022.104022

Article Rights and License

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Sprint Investify. ISSN 2359-7712. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.