Keywordscommitment loyalty reputation satisfaction service quality trust

JEL Classification M31

Full Article

1. Introduction

The development of information and communication technology (ICT) is rapidly transforming how industries and sectors operate. It is not peculiar to the higher education sector (Chow and Shi, 2014), with online learning increasingly emerging as the new dominant model for higher education institutions (Ansari and Sanayei, 2012). E-learning is a type of teaching and learning method that makes use of telecommunications technology (Ansari and Sanayei, 2012; Beqiri, Chase, and Bishka, 2010). It offers several advantages for both higher learning institutions and learners (Bhuasiri, Xaymoungkhoun, Zo, Rho and Ciganek, 2012). It assists higher education institutions to save costs associated with the infrastructure, become more computerized and participate to the evolution of a modern and informed society, furthermore universities are able to effectively integrate with the global educational system (Lee, 2010). In terms of student benefits, E-learning offers a digitised learning platform and flexibility (Bhuasiri et al., 2012), breaks geographical barriers, and offers convenience for part-time students (Kilburn et al., 2014).

E-learning has increasingly become the dominant and preferred method for higher education institutions due to its high speed of information transmission in a cost-effective manner (Ayuni and Mulyana, 2019). Higher learning institutions continuously face intense local and international competition (Masserini et al., 2019), leading to challenges of student attraction and retention (Latif and Bahroom 2014; Martinez–Arguelles and Batalla–Busquets, 2016). These institutions are regarded as business entities committed to delivering programs to students as their customers (Goolamally and Latif, 2014b). Similar to any service sector, keeping a customer base is far less expensive than acquiring a new one. Therefore, student retention strategies have become important because a good student–university relationship is likely to reduce the drop-out rate and increase student commitment (Goolamally and Latif, 2014b; Latif and Bahroom, 2014; Martinez–Arguelles and Batalla–Busquets, 2016). In addition, higher education institutions need to establish progressive responsive strategies to forge relationships with students (Ayuni and Mulyana, 2019), which necessitates critical analysis of students’ preconceptions (Lai, Pham and Le, 2019). Moreover, to satisfy students and develop student loyalty, universities need insightful approaches and strategies to develop the most versatile and flexible learning environment (Goolamally and Latif, 2014b).

Student satisfaction and loyalty in the traditional education sector have received considerable attention (Herman, 2017; Mwiya, Bwalya, Siachinji, Sikombe, Chanda and Chawala, 2019). However, few research efforts have focused on the factors that drive student satisfaction and loyalty in open distance electronic learning (ODeL) institutions. According to Latif and Bahroom (2014), more research is required to understand the concept of relationship marketing in institutions of higher learning, particularly in traditional and ODeL institutions. Bakrie, Sujanto, and Rugaiyah (2019) suggest that future research should investigate influential factors including commitment on student loyalty, as well as the moderating influence between student satisfaction, service quality and institutional reputation on student loyalty. Furthermore, Pham, Limbu, Bui, Nguyen, and Pham (2019) state the need for researchers to investigate the effect of an institutions’ reputation, perceived value and service quality on students’ satisfaction and loyalty. Researchers should also determine the influence of cultural differences on e-learning’s student satisfaction and student loyalty and compare the overall e-learning quality in different countries (Pham et al., 2019). Thus, ODeL institutions should understand the factors that have an effect on student satisfaction and loyalty to attract and retain students (Goolamally and Latif, 2014b).

The purpose of this study is to fulfil the gap by identifying the factors that influence student satisfaction and loyalty, and the mediating effect of student satisfaction on student loyalty in the South African ODeL institutions. As a result, the following study objectives were established for this study:

- To determine the factors that influence students’ satisfaction and loyalty in ODeL institutions

- To determine the mediating effect of students’ satisfaction on student loyalty in ODeL institutions

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theory Underpinning the Study

Research on student loyalty has focused on the student’s drop-out behavior model by Tinto (1975). Tinto’s (1975) model suggests that a student’s commitment is the key to fostering student loyalty. It also argues that commitment is divided into three parts: objective commitment, institutional commitment, and external pledges such as the student’s activities outside the institution that may compromise the student’s loyalty to the higher education institution (Tinto, 1975).

The model has been criticized for evaluating students’ commitments in aspects that are reflected secondarily. Furthermore, the model included the value of instruction as a factor that influences student loyalty, instead of it being the underlying cause of the problem (Goolamally and Latif, 2014b). Tinto’s model, on the other hand, is thought to be the ideal model for future research on student loyalty initiatives in higher education institutions (Goolamally and Latif, 2014b). Thus, Tintos drop-out behavior model provides a solid underpinning theory for the study based on the aforementioned premises.

2.2. ODeL institutions in South Africa

ODeL has evolved into an effective strategy for addressing access to education challenges in most developed and developing countries (Ofole, 2018). Through ODeL, approximately 30 000 education students at the Potchefstroom Campus in North-West University in South Africa achieved their qualifications remotely (Esterhuizen, 2015). African ODeL institutions rely on modern, affordable ICT to distribute learning materials (Tladi, 2018). The University of South Africa (UNISA) is South Africa’s only comprehensive ODeL institution with a mixed-mode approach (Manyike, 2017). UNISA’s transition to an ODeL has provided various teaching, learning, and research opportunities, particularly for students in remote areas (Kunene and Barnes, 2017). It has also played an important role in providing a convenient platform for learning anytime and anywhere, especially in a country like South Africa, which is associated with poor governance and uprisings (Marimo, Mashingaidze and Nyoni, 2013).

2.3. Factors Influencing Student Satisfaction and Loyalty in ODeL Institutions

Previous studies in the traditional learning education sector suggest that service quality and satisfaction are pivotal attributes that promote student loyalty (Parves and Ho, 2013). Goolamally and Latif (2014b) further state that the key predictors of student loyalty in ODeL institutions are service quality, satisfaction, trust, and emotional commitment. Previous researchers propose that future studies should investigate the influence of perceived value on the correlation between service quality and students’ satisfaction and loyalty in an e-learning context (Pham et al., 2019; Rodic et al., 2018). Wong et al., (2017) state that examining students’ satisfaction in relation to institutional reputation and branding is important in improving teaching quality. Pham et al. (2019) further state the need for researchers to examine the moderating effect between service quality and students’ satisfaction and loyalty in an e-learning environment. Following the gaps identified and future direction as suggested by former researchers, this study examines the effect of commitment, service quality, perceived value, institution reputation and trust on students’ satisfaction and loyalty in South African ODeL institutions.

2.3.1. Loyalty and Satisfaction

Student loyalty is an important aspect in a higher education institutions development and sustainability (Goolamally and Latif, 2014b). Student loyalty alludes to an event where a student remains in the same institution to complete several qualifications and suggests it to others through word-of-mouth (Bowen and Shoemaker, 1998). Customer satisfaction, on the other hand, is an assessment of the perceived gap between expectations and actual usage (Han and Ryu, 2009). It is a crucial concept in marketing that aids practitioners to meet the customers’ requirements and desires (Martinaityte et al.,2019). In higher education, several studies have found a direct positive effect of student satisfaction on student loyalty (Ali et al., 2016; Clemes et al., 2013; Dehghan et al., 2014; Herman, 2017; Martinez-Arguelles and Batalla-Busquets, 2016). According to Pham et al., (2019), e-learning student satisfaction is a key to student loyalty. Furthermore, it has a significant influence on students’ loyalty in e-learning institutions (Ansari and Sanayei, 2012; Ayuni and Mulyana, 2019). Goolamally and Latif (2014a, 2014b) also discovered that student satisfaction had a considerable impact on student loyalty, prompting the following hypothesis:

H1: Student satisfaction influences student loyalty.

2.3.2. Commitment

Chen (2017) describes students’ commitment as a strong conviction in and appreciation of a higher education institution, as well as the intention to maintain the relationship with the institute. Goolamally and Latif (2014b) state that students’ commitment to an institution is the basis of a meaningful partnership. Any educational institution’s primary goal should be to increase students’ commitment to the institution. The level of students’ commitment to the institution increases if students can study and thrive in their current institutions. Several researchers, including (Sharma, 2015), have discovered that students’ commitment to higher education institutions has a positive and significant impact on student satisfaction. Chen (2017) found that students’ commitment to higher education institutions has a direct impact on their satisfaction. Furthermore, Xiao and Wilkins (2015) discovered that student satisfaction is closely linked to their commitment and educational success.

Pritchard, Havitz, and Howard (1999) state that customer loyalty can only be accomplished through commitment. Latif and Bahroom (2014) agree by showing that student commitment has a significant impact on student loyalty (Latif and Bahroom, 2014). Other researchers have also discovered that student commitment has a direct impact on student loyalty (Goolamally and Latif, 2014b; Latif and Bahroom, 2014). Therefore, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H2: Student commitment influences student satisfaction.

H3: Student commitment influences student loyalty.

2.3.3. Service Quality

One of the most important aspects influencing student satisfaction has been identified to be service quality (Mwiya et al., 2019). Service quality is defined by Goolamally and Latif (2014b) as a range of services offered by a higher education institution which includes the efficiency of the education process, study tools, and facilities. It is possible to achieve student satisfaction by delivering high-quality academic support (Mohamad and Awang, 2009). Education quality, management service, service centre, and technology readiness are all components of e-learning service quality (Ayuni and Mulyana, 2019). In the traditional educational industry, student satisfaction is influenced by service quality (Mulyono, 2014). According to Mwiya et al., (2019), distance learning students benefit more from the quality of service and total student satisfaction than traditional full-time students. Ayuni and Mulyana, 2019) concurs by stating that E-learning service has a major impact on student satisfaction. To confirm these statements, Pham et al., (2019) discovered that e-learning service quality is positively linked to student satisfaction. In ODeL institutions, Goolamally and Latif (2014b) discovered that service quality has a direct impact on student satisfaction. This is in line with prior study, which revealed that service quality in ODeL institutions had a significant impact on student satisfaction (Martinez-Arguelles and Batalla-Busquets, 2016; Dehghan et al., 2014).

Student satisfaction, according to Goolamally and Latif (2014b), influences the correlation between service quality and loyalty. Pham et al., (2019) assert that E-learning service quality has an indirect effect on e-learning student loyalty through e-learning student satisfaction. This means that Student loyalty is impacted by service quality (Goolamally and Latif, 2014b). Previous research has revealed that the quality of service has an impact on student loyalty (Martinez-Arguelles and Batalla-Busquets, 2016; Mohamad and Awang, 2009 and Dehghan et al., 2014). Furthermore, the quality of an e-learning service has been found to have substantial impact on student loyalty (Ayuni and Mulyana, 2019), especially In ODeL institutions (Latif and Bahroom (2014). Yet, a 2012 study by Dado et al. revealed no correlation between service quality and student loyalty. As a result, the hypotheses outlined below were developed:

H4: Student satisfaction is influenced by service quality.

H5: Student loyalty is influenced by service quality.

2.3.4. Institution Reputation

Research provides evidence of the increasing importance of institutional reputation in higher learning institutions (Parahoo et al., 2013). The reputation of an institution is established through the years by continuously reaching and surpassing its intended goals. As a result, students’ perceptions of the institution’s reputation are used to gauge satisfaction, particularly in open distance learning environments where students engage with the institution virtually (Parahoo et al., 2016). Institutional reputation increases student satisfaction, meaning a university with a high reputation will have more influence on student satisfaction (Bakrie et al., 2019). Parahoo, Santally, Rajabalee, and Harvey (2016) state that a university’s reputation positively influences student satisfaction in online learning. Ali, Zhou, Hussain, Nair, and Ragavan (2016) confirmed this by observing that a university’s reputation significantly influences student satisfaction. Moreover, in a study examining the factors that influence student satisfaction regarding online undergraduates, Helgesen and Nesset (2007) discovered a significant correlation between reputation and loyalty. Thus, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H6: Institutional reputation influences student satisfaction.

2.3.5. Perceived Value

According to Mbango and Toerien (2019), the correlation between customer value and customer satisfaction has garnered minimal interest. Lusch and Vargo (2014) suggest that customer value in competitive markets is an important factor to consider for survival and prosperity. Consumer value is defined by Hellier, Geursen, Carr, and Rickard (2003) as an assessment of the quality of a product or service. Customer value influences customer satisfaction (Mbango, 2019). In education, Clemes, Cohen, and Wang (2013) content that perceived value has little effect on student satisfaction. Brown and Mazzarol (2009), on the other hand, discovered that perceived value has a significant impact on student satisfaction. Teeroovengadum, Nunkoo,Gronroos, Kamalanabhan, and Seebaluck (2019) also foundperceived value to influence student satisfaction in higher education. Kilburn, Kilburn, and Cates (2014) examined the determinants of student loyalty in online higher learning institutions. The findings reveal a strong correlation between perceived value and student loyalty. Therefore, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H7: Perceived value influences student satisfaction.

H8: Perceived value influences student loyalty.

2.3.6. Trust

Trust, according to Han and Hyun (2015), is the belief that an individual’s promise is trustworthy and that a member in the partnership will execute their obligations. Student trust in higher education institutions can be defined as a student’s confidence in the reliability of the institution’s staff members (Rodi Luki and Luki, 2018). Therefore, it can be said that trust is built through observations and experiences students have encountered with the institution.

Student trust positively and significantly influences student satisfaction (Kunanusorn and Puttawong, 2015). This is supported by Chen (2017), who found student trust to directly influence student satisfaction in higher education institutions. Herman (2017) examined aspects that affect student loyalty in higher education. The author found that student trust significantly influences students’ loyalty. According to Goolamally and Latif (2014a, 2014b) and Latif and Bahroom (2014) student trust significantly influences student loyalty in ODeL institutions. Furthermore, it has been discovered that trust acts as a mediator between service quality and student loyalty (Goolamally and Latif 2014b). Therefore, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H9: Student trust influences student loyalty.

H10: Student trust influences student satisfaction.

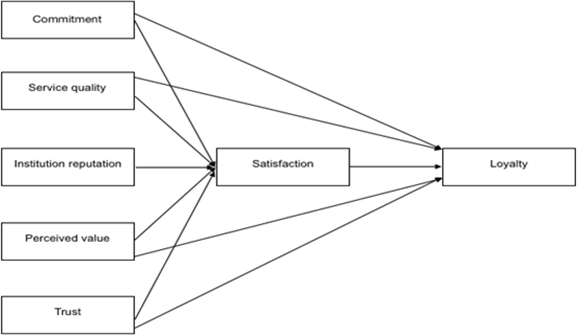

Figure 1. Conceptual model

Source: Own creation

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Population Sample

The quantitative approach using the survey method was used to collect the data through a self-administered questionnaire online survey because of the Covid-19 pandemic which made personal interviews impossible. The site of the survey was conducted at one of the biggest universities in South Africa and the African continent.

3.2. Research Design, and Sample Size

The study followed the purposive and convenience sampling methods in selecting the participants. There are 1500 registered students in the College of Economics and Management Sciences which were e-mailed web-based questionnaires. The College of Economics and Management Sciences was chosen because of its diverse student population as well as being the biggest College of the chosen site of study. 1439 responses were received, representing 95.93% response rate.

3.3. Data Collection, Measures, and Analytical Strategy

Data was collected from the Lime Survey platform. The process involved the conversion (as close as possible to the original) of the paper-based questionnaire for use on the online platform, setup of the database to receive the completed responses, and exporting of the final data in a format usable for a statistician (SPSS/Excel). The target group received the link to the online survey.

The research constructs were developed solely on already validated measures and approved by research experts who are relevant in the field of study topic for validity and reliability. All scale items were rearticulated to relate to the context of the current study’s requirement. A seven-point Likert scale was employed to measure the constructs ranging from ‘1 - strongly disagree’ to ‘7 - strongly agree’.The questionnaire was divided into three parts: Part A contains the introduction, Part B the demographic profile (gender, age, as well as the course/degree the student is studying towards), and Part C questions about the variables.First, the ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Department of Marketing and Retail Management (Ref. 2020_MRM_008) and the University Research Permission Sub-Committee (Ref. 2020_RPSC_040).

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The sample and constructs’ descriptive characteristics were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 26. Tables 1 and 3 present the results of the descriptive characteristics of the sample and constructs, respectively. Of the 1439 participants, 917 (63.7%) were males, 505 (35.1%) females, and 17(1.2%) undisclosed gender. The majority of the participants (38.2%) were aged between 21 and 30 years, followed by 37.2% aged between 31 and 40. In total, over two-thirds of the sample comprises participants aged between 21 and 40 comprised. Moreover, 66.1% were Africans, followed by Whites (15.45%), Coloureds (7.7%), Indians (6.7), and Asians (0.3). Lastly, 36.7% of participants were registered for a higher certificate, followed by 32.5% registered for a bachelor’s degree, 7.6% for an honors degree, 1.3% for master’s and 0.6% for a doctorate. What is noteworthy is that the sample reflects students of all the major qualifications in the institution. Table 1 presents the results of the descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) of the constructs. The mean estimates for the constructs ranged from 4.886 (SD = 1.579) to 6.019 (SD = .961) show that all the mean estimates are above the midpoint of the seven-point scale, suggesting that most of the participants agreed with the statements measuring the constructs.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of the sample

| Sample characteristics | Frequency | Percent | |

| Gender | Male | 917 | 63.7 |

| Female | 505 | 35.1 | |

| Prefer not to say | 17 | 1.2 | |

| Age | 18 - 20 years | 57 | 4.0 |

| 21 - 30 years | 549 | 38.2 | |

| 31 - 40 years | 536 | 37.2 | |

| 41 - 50 years | 238 | 16.5 | |

| 51-65 years | 59 | 4.1 | |

| Cultural group | African | 951 | 66.1 |

| Asian | 4 | .3 | |

| Coloured | 111 | 7.7 | |

| Indian | 97 | 6.7 | |

| White | 222 | 15.4 | |

| I prefer not to say | 54 | 3.8 | |

| Level of qualification | Higher Certificate | 528 | 36.7 |

| Diploma | 308 | 21.4 | |

| Degree | 467 | 32.5 | |

| Honors | 110 | 7.6 | |

| Masters | 18 | 1.3 | |

| PhD/Doctorate | 8 | .6 | |

Source: Own creation

4.2. Validity of Measurement Model

To test the proposed model, the study used partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling using SmartPLS version 3.6. This technique is considered appropriate since the study aims to analyze how the independent variables predict loyalty (Hair 2020). In testing the research model, the study first assessed the validity of the measures of the construct and then assessed the structural model to determine the hypotheses. The validity of the measurement model was examined through its convergent and discriminant validity. Standardized loadings of the factors, composite reliability, and average variance extracted (AVE) were used to assess the convergent validity.

The results for these metrics are presented in Table 2. Accordingly, the standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.733 (for CMT3) to 0.946 (SAT3), meeting the recommended threshold of 0.708 for convergent validity of the measurement model (Hair, Howard and Nitzl, 2020). The composite reliability values estimated for the present study ranged from 0.903 (commitment) and 0.966 (satisfaction). According to Hair et al. (2020), to achieve valid convergent validity, the estimates for composite reliability should exceed 0.7. This further provides evidence of convergent validity. Lastly, as a measure of convergent validity, AVEs were also considered. Hair et al. (2020) emphasized that for a measurement model to achieve convergent validity, the AVEs for each construct should exceed 0.5. From the results presented in Table 2, the least of the AVE estimates is 0.652. This is greater than the minimum cut-off of 0.5, thus providing further support for the convergent validity of the measurement model.

Table 2. Convergent validity of measurement model

| Construct and Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s alpha | Composite reliability | Average variance extracted |

| Commitment | 0.868 | 0.903 | 0.652 | |

| CMT1 | 0.754 | |||

| CMT2 | 0.861 | |||

| CMT3 | 0.733 | |||

| CMT4 | 0.849 | |||

| CMT5 | 0.833 | |||

| Loyalty | 0.873 | 0.912 | 0.722 | |

| LOY1 | 0.879 | |||

| LOY2 | 0.889 | |||

| LOY3 | 0.830 | |||

| LOY4 | 0.798 | |||

| Reputation | 0.942 | 0.952 | 0.686 | |

| REP1 | 0.812 | |||

| REP2 | 0.754 | |||

| REP3 | 0.862 | |||

| REP4 | 0.849 | |||

| REP5 | 0.856 | |||

| REP6 | 0.809 | |||

| REP7 | 0.786 | |||

| REP8 | 0.864 | |||

| REP9 | 0.857 | |||

| Satisfaction | 0.955 | 0.966 | 0.848 | |

| SAT1 | 0.903 | |||

| SAT2 | 0.939 | |||

| SAT3 | 0.946 | |||

| SAT4 | 0.916 | |||

| SAT5 | 0.901 | |||

| Service Quality | 0.900 | 0.926 | 0.715 | |

| SQL1 | 0.807 | |||

| SQL2 | 0.881 | |||

| SQL3 | 0.888 | |||

| SQL4 | 0.835 | |||

| SQL5 | 0.814 | |||

| Trust | 0.880 | 0.926 | 0.807 | |

| TRT1 | 0.898 | |||

| TRT2 | 0.919 | |||

| TRT3 | 0.878 | |||

| Value | 0.890 | 0.923 | 0.752 | |

| VLU1 | 0.759 | |||

| VLU2 | 0.908 | |||

| VLU3 | 0.909 | |||

| VLU4 | 0.882 | |||

Source: Own creation

After confirming the convergent validity of the measurement model, the study assessed discriminant validity using both the Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) technique and the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations. Discriminant validity is present when the square root of the AVE for each construct is greater than the inter-construct correlations (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). The square root of the AVEs (bold diagonal values) is greater than the inter-construct correlations (values beneath the diagonal values) (Table 3), thus satisfying the condition of discriminant per the Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) method.

Regarding the HTMT criteria, discriminant validity is present when the HTMT ratio of correlations is less than either 0.85 or 0.90 (Henseler, Ringle and Sarstedt, 2015). The HTMT ratio of correlations (values above the bold diagonal values) is less than the liberal HTMT threshold of 0.9, thus providing further evidence of the discriminant validity of the measurement model (Table 3). The confirmation of both the convergent and discriminant validity of the measurement model assured the validity of the measures of the constructs for the hypotheses testing.

Table 3. Discriminant validity

| Construct | Mean | SD | Correlation matrix | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||||

| 1 | Commitment | 6.019 | .961 | 0.807 | 0.779 | 0.724 | 0.626 | 0.656 | 0.736 | 0.711 |

| 2 | Loyalty | 5.298 | 1.175 | 0.700 | 0.850 | 0.777 | 0.783 | 0.753 | 0.736 | 0.788 |

| 3 | Reputation | 5.402 | 1.126 | 0.668 | 0.714 | 0.828 | 0.825 | 0.867 | 0.781 | 0.776 |

| 4 | Satisfaction | 4.886 | 1.579 | 0.594 | 0.729 | 0.784 | 0.921 | 0.892 | 0.832 | 0.799 |

| 5 | Service quality | 4.964 | 1.410 | 0.600 | 0.678 | 0.799 | 0.828 | 0.846 | 0.860 | 0.753 |

| 6 | Trust | 5.219 | 1.204 | 0.616 | 0.657 | 0.713 | 0.764 | 0.767 | 0.898 | 0.714 |

| 7 | Value | 5.447 | 1.221 | 0.646 | 0.716 | 0.727 | 0.753 | 0.689 | 0.648 | 0.867 |

Source: Own creation

Note: *Bold diagonal estimates are the square root of the AVEs. Values above the diagonal estimates are the HTMT ratio of corrections and values below the inter-factor correlations.

The structural model was assessed to determine the significance of the hypotheses, the coefficient of determination, and the effect sizes. However, before testing the hypotheses, the level of collinearity among the exogenous constructs was assessed using the variance inflation factors (VIFs). The VIF estimates obtained for the present study ranged from 2.089 to 4.494. These estimates are less than the generally accepted threshold of 5 for critical levels of collinearity. Thus, collinearity is not of critical levels in the present study.

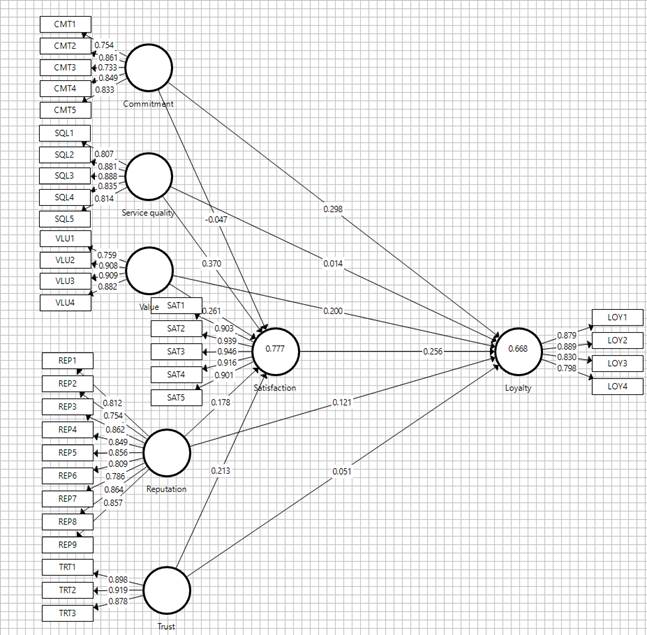

Figure 2. Results of the PLS model analysis

Source: Own creation

The results of the hypotheses testing for the direct relationships are presented in Table 4. Accordingly, commitment has a significant and negative relationship with student’s satisfaction (β= - 0.047; p < 0.05); this partially support H1. Service quality has a significant and positive relationship with satisfaction (β= 0.370 p < 0.001); this supports H2. Regarding H3, the perceived value has a significant positive relationship with students’ satisfaction with the university (β= 0.261 p<0.001); therefore, H3 is supported. Students’ perception of the institutional reputation has a significant and positive association with their satisfaction (β= 0.178; p<0.001); thus, H4 is statistically supported.

Further, student’s trust in the institution also has a significant and positive impact on their satisfaction with the institution (β= 0.213; p<0.001), supporting H5. Furthermore, students’ satisfaction with the institution influences their loyalty to the institution (β= 0.256; p<0.001), supporting H6.

The study also sought to examine how the same antecedents of student’s satisfaction with the institution influence their loyalty. The results show that while students’ commitment to the institution has a significant impact on their loyalty (β=0.298, p<0.001), their perception of service quality provided by the institution did not have a significant impact on their loyalty (β=0.014; p>0.05). Therefore, H7 is supported, but H8 is rejected. The results also suggest that students’ perception of value (β=0.200; p < 001) and institutional reputation (β=0.121, p<0.001) are significant and positively related to their loyalty to the institution, thus providing statistical support for H9 and H10.

On the contrary, students’ trust in the institution is not significantly related to their loyalty (β=0.051, p>0.05). In addition, 77.7% of the variance in students’ satisfaction with the institution is explained by its significant antecedents (i.e., commitment, service quality, perceived value, reputation, and trust) (Figure 2). The results also show that 66.8% of the variance in student’s loyalty is explained by its significant antecedents: satisfaction, commitment, perceived value, and reputation.

Table 4. Results of PLS Hypotheses testing – Direct effects

| Path coefficient | 95% Bias Corrected CI | f2 | Effect size | |

| Commitment → Satisfaction | -0.047* | [-0.095; -0.005] | 0.005 | Weak |

| Service quality → Satisfaction | 0.370*** | [0.301; 0.428] | 0.170 | medium |

| Value → Satisfaction | 0.261*** | [0.209; 0.315] | 0.122 | Small |

| Reputation → Satisfaction | 0.178*** | [0.122; 0.243] | 0.039 | Small |

| Trust → Satisfaction | 0.213*** | [0.158; 0.263] | 0.073 | Small |

| Satisfaction → Loyalty | 0.256*** | [0.181; 0.340] | 0.044 | Small |

| Commitment → Loyalty | 0.298*** | [0.216; 0.344] | 0.128 | Small |

| Service quality → Loyalty | 0.014ns | [0.039; 0.184] | 0.000 | Weak |

| Value → Loyalty | 0.200*** | [0.208; 0.320] | 0.043 | Small |

| Reputation → Loyalty | 0.121*** | [0.090; 0.245] | 0.012 | Weak |

| Trust → Loyalty | 0.051ns | [0.046; 0.167] | 0.003 | Weak |

Source: Own creation

Note: f2 (effect size); estimates above 0.35= large effect; 0.15 – 0.35 = medium effect and 0.02 – 0.15 small effect (Cohen, 1998).

The study also sought to analyze how the impacts of commitment, institutional reputation, service quality, trust, and perceived value on loyalty are mediated by student’s satisfaction with the institution. Therefore, the study computed and examined indirect effects and total effects of relationships. All the indirect effects and total effects of the relationships are significant (Table 5).

According to Zhao, Lynch, and Chen (2010), mediation exists when the indirect effect of the relationship is significant. A significant indirect effect of a mediated relationship is partial when both direct and indirect effects are significant. It is full when the indirect relationship is significant, but the direct relationship is not. As seen in Table 5, 3 out of the 5 relationships are partially mediated by satisfaction, whereas 2 are fully mediated. That is, the impact of commitment, institutional reputation, and perceived value on loyalty are partially mediated by satisfaction. In contrast, the impact of service quality and trust on loyalty is fully mediated by students’ satisfaction. This suggests that service quality and trust cannot influence students’ loyalty to the institution without satisfaction. The results of the mediation analysis generally suggest a partial mediation model proposed for the study.

Table 5. Results of the mediation analysis (own creation)

| Direct effect | Indirect effect | Total Effect | Mediation | |

| Commitment → Loyalty | 0.298*** | -0.012* | 0.286*** | Yes, partial |

| Reputation → Loyalty | 0.121** | 0.046*** | 0.167*** | Yes, partial |

| Service quality → Loyalty | 0.014ns | 0.095*** | 0.109** | Yes, full |

| Trust → Loyalty | 0.051ns | 0.054*** | 0.105*** | Yes, full |

| Value → Loyalty | 0.200*** | 0.067*** | 0.267*** | Yes, partial |

Source: Own creation

Note: ***p>0.001; **p>0.01; *p>0.05 ns = non-significant path

5. Discussion and Conclusion

The PLS-SEM technique was used to analyze eleven hypotheses. The results indicated that student satisfaction is influenced by commitment, reputation, trust, and value, with service quality being the most significant contributing factor. The study corroborates Parahoo et al., (2016), who found that the university’s reputation influences student satisfaction. It is also consistent with Rodic and Lukic (2018) and Paul and Pradhan (2019), who found that service quality is the most significant factor influencing student satisfaction in higher education institutions.

Variability in student loyalty is explained to a greater extent by student satisfaction, commitment, and value. Reputation, service quality, trust also influence student loyalty, although to a lesser degree; this finding corroborates Ali et al., (2016), who found student satisfaction influences student loyalty in higher education institutions. It is also consistent with Pham et al., (2019), who found that service quality influences student loyalty in e-learning institutions, and consistent with Kilburn et al., (2014), who found that perceived value significantly influences student loyalty in e-learning higher education institutions.

The study revealed that commitment, reputation, service quality, trust, and value have a direct and indirect effect on student loyalty, mediated by student satisfaction. This supports Yusuf (2019), who found that student satisfaction mediates the relationship between service quality and student loyalty. Yusuf (2019) also found that institutional image (reputation) has an indirect effect on student loyalty through student satisfaction. Furthermore, Herman (2017) discovered that student satisfaction has a mediating effect on trust and student loyalty.

Changes in the economic and social landscape caused by Covid-19 have forced many traditional educational institutions to incorporate online learning as a channel of service delivery. The model derived from this study has theoretical and practical contributions in the education sector, especially in Africa, where online learning is still in its infancy. The study explored the mediating effects of student satisfaction on student loyalty rather than the correlations between different factors through PSL SEM, which has been limitedly explored in the education sector, especially in an ODeL context. The study will serve as a guideline to traditional institutions that want to adapt to the blended teaching approach and to those who want to go fully online on how to better service, create value through convenience and retain their students in these ever-changing times.

5.1. Managerial Implications

The findings of the study have several important managerial implications. Knowing and understanding the service quality dimensions on student satisfaction and loyalty will help ODeL institutions manage resources more effectively to provide better service. These institutions will be conscious of the important role an institution’s image plays in attracting prospective students and obtaining a competitive advantage. Finally, the direct and indirect effects of all the factors on student loyalty mediated through student satisfaction have several suggestions. That is, to maximize student satisfaction and loyalty, universities must focus on creating sustainable value, fostering trust and commitment, and improving the service quality. These outcomes have favorable implications for the institution’s success.

5.2. Limitations of Study and Future Directions of Research

The study was conducted at one ODeL institution; therefore, the sample can be considered small. Thus, the findings may not reflect the perceptions of all students in ODeL institutions. However, the findings set the foundation for future studies in other sectors.The study focused on the perceptions of students and excluded the views of academics and management. Future studies can be conducted from an academic and management perspective. However, because the existing literature on student loyalty and satisfaction in African ODeL institutions is limited, this study serves as the basis for future research.

---

Author Contributions: Phineas Mbango and Kate Ngobeni: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data analysis, Writing- Original draft preparation, Visualization, Investigation, Software, Validation, Writing- Reviewing.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance offered by the University of South by providing support in allowing data collection to take place. We would like to acknowledge the language editor and statistician from University of South Africa.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- Ali, F., Zhou, Y., Hussain, K., Nair, P.K. and Ragavan, N.A., 2016. Does higher education service quality effect student satisfaction, image and loyalty?. Quality assurance in education, 24 (1), pp. 70-94.

- Ansari, A. and Sanayei, A., 2012. Determine the effects of mobile technology, mobile learning on customer satisfaction and loyalty (Case study: Mellat Bank). International Journal of Information Science and Management (IJISM), pp. 137-152.

- Ayuni, D. and Mulyana, A., 2019. Applying Service Quality Model as a Determinant of Success in E-learning: The Role of Institutional Support and Outcome Value. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research, 8, pp. 145-159.

- Bakrie, M., Sujanto, B. and Rugaiyah., R., 2019. The Influence of Service Quality, Institutional Reputation, Students’ Satisfaction on Students’ Loyalty in Higher Education Institution. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Studies, 1(5), pp. 379-391.

- Beqiri, M., Chase, N. and Bishka, A., 2010. Online course delivery: An empirical investigation of factors affecting student satisfaction. Journal of Education for Business, 85, pp. 95–100.

- Bhuasiri, W., Xaymoungkhoun, O., Zo, H., Rho, J. J. and Ciganek, A. P., 2012. Critical success factors for e-learning in developing countries: A comparative analysis between ICT experts and faculty. Computers and Education, 58(2), pp. 843-855.

- Bowen, J. and Shoemaker, S., 1998. Loyalty: A Strategic Commitment. Cornell Quarterly, 39, pp. 12-25.

- Bourner, T., 2011. Action Learning over time: an ipsative enquiry. Action Learning: Research and Practice, 8(1), pp. 43-56.

- Brown, R.M. and Mazzarol, T.W., 2009. The importance of institutional image to student satisfaction and loyalty within higher education. Higher education, 58(1), pp. 81-95.

- Chen, Y.C., 2017. The relationships between brand association, trust, commitment, and satisfaction of higher education institutions. International Journal of Educational Management, 31(7), pp. 973-985.

- Chow, W. S. and Shi, S., 2014. Investigating students’ satisfaction and continuance intention toward e-learning: An extension of the expectation–confirmation model. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 141, pp. 1145-1149.

- Clemes, M.D., Cohen, D.A. and Wang, Y., 2013. Understanding Chinese university students’ experiences: an empirical analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 25(3), pp. 391-427.

- Dado, J., Petrovicova, J. T., Riznic, D. and Rajic, T., 2011. International review of management and marketing an empirical investigation into the construct of higher education service quality. International Review of Management and Marketing, 1(3), pp. 30-42.

- Dehghan, A., Dugger, J., Dobrzykowski, D. and dan Balazs, A., 2014. The Antecedents of Student Loyalty In Online Programs. International Journal of Educational Management, 28(1), pp. 15-35.

- Esterhuizen, H., 2015. Technology Enhanced Learning in Open Distance Learning at NWU. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 14 (3), pp. 120-137.

- Goolamally, N. and Latif, L. A., 2014a. Determinants of student loyalty in an open distance learning institution. In Seminar Kebangsaan Pembelajaran SepanjangHayat, pp. 390-400.

- Goolamally, N. and Latif, L. A., 2014b. Validating the student loyalty model for an open distance learning institution. ASEAN Journal of Open and Distance Learning (AJODL), 6(1), pp. 78-88.

- Han, H. and Ryu, K., 2009. The roles of the physical environment, price perception, and customer satisfaction in determining customer loyalty in the restaurant industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 33(4), pp. 487-510.

- Hair Jr, J.F., 2020. Next-generation prediction metrics for composite-based PLS-SEM. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 121(1), pp. 5-11.

- Han, H. and Hyun, S.S., 2015. Customer retention in the medical tourism industry: Impact of quality, satisfaction, trust and price reasonableness. Tourism Management, 46, pp. 20-29.

- Hellier, P. K., Geursen, G. M., Carr, R.A. and Rickard, J.A., 2003. Customer repurchase intention: A great structural equation model. European Journal of Marketing, 37(11/12), pp. 1762-1800.

- Henning-Thurau, T., Lager, M.F. and Hansen, U., 2001. Modelling and managing student loyalty: an approach based on the concept of relationship quality. Journal of Service Research, 3(1), pp. 331-44.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M. and Sarstedt, M., 2015. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 43(1), pp. 115-135.

- Helgesen, O. and Nesset, E., 2007. Images, satisfaction and antecedents: Drivers of student loyalty? A case study of a Norwegian university college. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(1), pp. 38-59.

- Herman, H., 2017. Loyalty, Trust, Satisfaction and Participation in Universitas Terbuka Ambiance: Students’ Perception. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 18(3), pp. 84-95.

- Kilburn, A., Kilburn, B. and Cates, T., 2014. Drivers of student retention: System availability, privacy, value and loyalty in online higher education. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 18(4), pp. 1-14.

- Kunanusorn, A. and Puttawong, D.D., 2015. The mediating effect of satisfaction on student loyalty to higher education institutions. European Scientific Journal, 1, pp. 449-463.

- Kunene, M.F. and Barnes, N., 2017. Perceptions of the open distance and e-learning model at a South African University. International Journal of Education and Practice, 5(8), pp. 127-137.

- Kuo, Y. K., and Ye, K. D., 2009. The causal relationship between service quality, corporate image and adults’ learning satisfaction and loyalty: A study of professional training programmes in a Taiwanese vocational institute. Total Quality Management, 20(7), pp. 749-762.

- Lai, S.L., Pham, H.H. and Le, A.V., 2019. Toward sustainable overseas mobility of Vietnamese students: understanding determinants of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty in students of higher education. Sustainability, 11(2), pp. 1-17

- Latif, L.A. and Bahroom, R., 2014. Relationship-based student loyalty model in an open distance learning institution, pp. 1-15.

- Lee, W.J., 2010. Online support service quality, online learning acceptance, and student satisfaction. Internet and Higher Education, 13, pp. 227-283.

- Lusch, R.F. and Vargo, S.L., 2014. The service-dominant logic of marketing: Dialog, debate and directions. London: Routledge.

- Manyike, T.V., 2017. Postgraduate supervision at an open distance e-learning institution in South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 37(2), pp. 1-11.

- Marimo, S.T., Mashingaidze, S. and Nyoni, E., 2013. Faculty of Education Lecturers’ and students’ perceptions on the utilization of e-learning at Midlands State University of Zimbwabwe. International Research Journal of Arts and Social Science, 2(4), pp. 91-98.

- Martínez-Argüelles dan J.-M. Batalla-Busquets., 2016. Perceived Service Quality and Student Loyalty in an Online University. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(4), pp. 264-279.

- Martinaityte, I., Sacramento, C. and Aryee, S., 2019. Delighting the customer: Creativity-oriented high-performance work systems, frontline employee creative performance, and customer satisfaction. Journal of Management, 45(2), pp. 728–751.

- Masserini, L., Bini, M. and Pratesi, M., 2019. Do quality of services and institutional image impact students’ satisfaction and loyalty in higher education?. Social Indicators Research, 146(1-2), pp. 91-115.

- Mbango, P. and Toerien, D.F., 2019. The role of perceived value in promoting customer satisfaction: Antecedents and consequences. Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1), pp. 1-16.

- Mwiya, B., Bwalya, J., Siachinji, B., Sikombe, S., Chanda, H. and Chawala, M., 2017. Higher education quality and student satisfaction nexus: evidence from Zambia. Creative Education, 8(7), pp. 1044-1068.

- Mohamad, M. and Z. Awang., 2009. Building Corporate Image And Securing Student Loyalty In The Malaysian Higher Learning Industry. The Journal of International Management Studies, 4(1), pp. 30-40.

- Mulyono, H., 2014. Mediating Effect Of Trust And Commitment On Student Loyalty. Business and Entrepreneurial Review, 14(1), pp. 57-76.

- Mwiya, B., Siachinji, B., Bwalya, J., Sikombe, S., Chawala, M., Chanda, H., Kayekesi, M., Sakala, E., Muyenga, A. and Kaulungombe, B., 2019. Are there study mode differences in perceptions of university education service quality? Evidence from Zambia. Cogent Business and Management, 6(1), pp. 1-19.

- Ofole, N.M., 2018. Curbing attrition rate in Open and Distance Education in Nigeria: e- counselling as a panacea. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

- Parahoo, S. K., Harvey, H. L. and Tamim, R. M., 2016. Factors influencing student satisfaction in universities in the Gulf region: Does gender of students matter?. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 23(2), pp. 135-154.

- Parahoo, S.K., Santally, M.I., Rajabalee, Y. and Harvey, H.L., 2016. Designing a predictive model of student satisfaction in online learning. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 26(1), pp. 1-19.

- Parves, S. and Ho Y, W., 2013. Antecedents and consequences of service quality in a higher education context: A qualitative research approach. Quality Assurance in Education, 21(1), pp. 70-95.

- Paul, R. and Pradhan, S., 2019. Achieving student satisfaction and student loyalty in higher education: A focus on service value dimensions. Services Marketing Quarterly, 40(3), pp. 245-268.

- Pham, L., Limbu, Y.B., Bui, T.K., Nguyen, H.T. and Pham, H.T., 2019. Does e-learning service quality influence e-learning student satisfaction and loyalty? Evidence from Vietnam. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16(1), pp. 1-26.

- Pritchard, M. P., Havitz, M. E. and Howard, D. R., 1999. Analyzing the Commitment- Loyalty Link in Service Contexts. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(3), pp. 333-348.

- Rodić Lukić, V. and Lukić, N., 2018. Assessment of student satisfaction model: evidence of Western Balkans. Total Quality Management and Business Excellence, pp. 1-13.

- Sharma, P., 2015. Organizational commitment among faculty members in India: a study of public and private technical schools. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 34(5), pp. 30-38.

- Teeroovengadum, V., Nunkoo, R., Gronroos, C., Kamalanabhan, T.J. and Seebaluck, A.K., 2019. Higher education service quality, student satisfaction and loyalty: Validating the HESQUAL scale and testing an improved structural model. Quality Assurance in Education, 27(40), pp. 427-445.

- Tladi, L., 2018. The requirements of success in an open, distance and eLearning (ODeL) institution: the case of Unisa (Doctoral dissertation). Unisa.

- Tinto, V., 1975. Drop-out from Higher Education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45, pp. 89-125.

- Wong, A., Tong, C. and Wong, J.W., 2017. The relationship between institution branding, teaching quality and student satisfaction in higher education in Hong Kong. Journal of Marketing and HR, 4(1), pp. 169-188.

- Xiao, J. and Wilkins, S., 2015. The effects of lecturer commitment on student perceptions of teaching quality and student satisfaction in Chinese higher education. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 37 (1), pp. 98-110.

- Yusuf, Y., 2019. Services quality and images: satisfaction and loyalty of students face to face tutorial services. AFEBI Management and Business Review, 4(1), pp. 48-59.

- Zhao, X., Lynch Jr, J. G. and Chen, Q., 2010. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), pp. 197-206.

Article Rights and License

© 2022 The Authors. Published by Sprint Investify. ISSN 2359-7712. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.