Keywordsbranding consumer-based brand equity South Africa wearable activity trackers

JEL Classification M30, M31, I11

Full Article

1. Introduction

Wearable activity tracking devices (WATs), also known as fitness trackers or activity trackers, by design have a combination of embedded accelerometers, SpO2 sensors, altimeters, barometers, thermometers, GPS chips and several other sensors that generate health-related and activity data such as heart rate data, step and distance data, calories burnt, floors climbed, active minutes and basic to advanced sleep data (Walker-Todd, 2021). Some other major and updated features include stress tracking, on-screen workouts for multi-sport profiles, food logging, blood oxygen tracking (Stables, 2021), and cardio load status and recovery. These metrics generated is executed by a pre-coded algorithm and complex software in conjunction with the sensors of the specific device, based on the user’s profile. The health benefits of using such devices are endless.

In accordance with the scope of this study, a wearable activity tracking device is defined as “any type of device that is attachable to the human body, including clothing items, capable of measuring the user’s movement and fitness-related metrics, whilst simultaneously providing real-time feedback by means of a smart device” such as a smartphone or desktop application or web service (Muller, 2019). Examples include fitness watches, fitness bands, head/arm/chest HR-straps, smart clothing such as smart socks, smart shoes or shirts/pants, smart jewellery such as necklaces and rings, clip on pedometers, head/ear phones.

The exponential growth and importance of the wearable tracker market are highlighted by the estimated US$134 million generated in 2021 (Statista, 2021) While growth is low and slow, new data shows the wearable device market is estimated to generate revenue close to US$134 million (approx. R1.8bn) in 2021, followed by the expected 48.2 billion USD by 2023 (Statista, 2021; P&S Market Research, 2018). South Africa recorded a WAT penetration rate of South Africa is reported to be the next big market for WAT devices and smartwatches (Business Tech, 2018), since, despite the lower penetrations rate (7.24 percent, with 4.3 million active paying users in 2020), the country ranked among 150 of the world’s leading digital economies for the wearables segment (Statista, 2020). The WAT market is crowded with brands competing for market share and revenue, both globally and in South Africa. Consequently, WAT brands need to find a way to stand out amongst the competition. This means going beyond research and development of the latest and most advanced devices to offer to consumers. Instead, the focus should shift to branding since people purchase brands, not products (Fearless, 2019).

Branding is the foundation for the success of any brand. From a consumer-oriented approach, a brand can be defined as: “the promise of the bundles of attributes that someone buys and provide satisfaction” (Ambler, 1992). Brands can be envisioned as living beings with an identity and personality, name, culture, vision, emotion and intelligence (The Economic Times, 2021). According to Chung, Jang & Han (2013), a brand may be classified as one of an company’s most important intangible assets. A brand communicates a promise to consumers regarding the product or service while signifying a set of brand values in the consumer’s mind (Kapferer, 2012). These values refer to everything the consumer considers to be important regarding the brand. Brand names are also a means of quality assurance and influence consumers’ brand choice (Strizhakova et al., 2011). Quality assurance can be based on the brand’s reputation, which is maintained through various touchpoints with consumers (Dranove & Jin, 2010). Brand reputation is among the most critical factors for a brand since it will inevitably determine consumers’ brand loyalty, brand trust and brand attachment.

Branding is broadly referred to as “the perpetual process of identifying, creating, and managing the cumulative assets and actions that shape the perception of a brand in stakeholders’ minds” (Dandu, 2015). Suitably, branding is recognised as one of the most essential marketing activities (Srinivasan et al., 2011) and has become a top management priority (Keller & Lehmann, 2006). Of note is the construct of brand equity, broadly described as the value of a brand as determined by consumers’ perception, be it positive or negative (Corporate Finance Institute, 2021). Various aspects influence the brand’s equity among consumers. This study will explore these brand equity dimensions, guided by the seminal consumer-based brand equity model of Aaker (1996), utilising modern branding scales to understand WAT brand perceptions better.

With the focus of enhancing brand equity, WAT brands will be able to charge premium prices for their products, transfer their equity to new product lines and increase their market share (Corporate Finance Institute, 2021) – enabling them to thrive in the WAT market. However, despite the substantial size of the WAT market and its revenue-generating capacity, there is a dearth of academic research regarding the brand equity of WAT brands, particularly in the South African context. To date, no academic literature is noted that investigated WAT brand equity. This study aims to explore the influence of consumer-based brand equity dimensions on the purchasing intentions of WAT brands among South African consumers. These findings will assist WAT brands in rethinking and optimising their branding strategy and better target this group of consumers.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Brand Equity

Brand equity refers to the value a brand adds to a product or service beyond its functional attributes. It represents the set of assets and liabilities associated with a brand that contribute to a product or service beyond its functional benefits (Kotler & Keller 2016, Lam, Hair & McDaniel, 2016; Jobber, 2010). In other words, branding is the increase in profit or demand based on the influence of the brand’s name (Kapferer 2008). Brand equity refers to “the power of a brand to create demand” (Cant & Van Heerden, 2013). A strong brand can provide significant added value to a company by creating a positive image, building customer loyalty, and commanding a premium price for its products or services due to the positive associations and emotions that customers have with the brand, as well as their perceptions of the brand's quality and reliability. Brand equity can differentiate a company's offering from its competitors and make it easier for the company to introduce new products or expand into new markets (Lamb et al., 2013; Du Toit & Erdis, 2013). By creating a positive image and reputation in the minds of consumers, a company can enjoy a competitive advantage and be better positioned for long-term success and ultimately lead to higher profits (Keller, 2013).

2.2. Measuring Brand Equity

Brand equity is a complex phenomenon and the measurement thereof is widely debated (Wood, 2000). Numerous brand equity models have been developed, of which the most prevalent model is Aaker’s (1996) (Klopper & North, 2011; Jooste, Strydom, Berndt & Du Plessis, 2012; Kotler & Keller, 2012). David Aaker is considered the father of modern branding based on his ground-breaking work regarding brand equity (Adamson, 2015). Aaker’s (1996) brand equity model comprises five dimensions namely: market behaviour, brand awareness, perceived quality, brand loyalty and brand associations. Aaker’s model makes use of a combination of firm-based and consumer-based brand equity. The consumer-based brand equity approach focuses on the consumers’ perception of the brand over time (Kotler & Keller, 2012) while the firm-based brand equity approach focuses on the impact of the brand on the financial performance of a company (Aggarwal, Rao & Popli, 2013).

Schiffman and Kanuk (2014) argue that consumer perceptions of the brand’s superiority influence the financial value of the brand. Consequently, brand equity may be considered a consumer-based concept. The market behaviour of a brand is the only brand equity measure (of the Brand Equity Ten) where no consumer inputs are required, as the measure utilises market share, market price and distribution coverage (Aaker, 1996). Consequently, this measure is relatively objective and quantifiable (Phipps, Brace-Govan & Jevons 2010). It should be noted that market behaviour aspects are not applicable when measuring consumer-based brand equity as it is considered as a firm-based approach to brand equity (Veloutsou, Christodoulides & De Chernatony, 2013). The remaining four categories are classified as antecedents of consumer-based brand equity.

2.3. Antecedents of Consumer-Based Brand Equity

Consumer-based brand equity is built over time through various brand-related experiences and marketing efforts and is influenced by factors such as brand awareness, brand loyalty, perceived quality, and brand associations. The higher the consumer-based brand equity, the more favourable and valuable the brand is perceived by consumers, leading to higher demand.

Brand Awareness

Brand awareness may be defined as the extent to which a consumer can recall and recognise a particular brand (Du Toit & Erdis, 2013). Brand awareness forms the foundation of brand equity (Kotler & Keller, 2012) and is the groundwork for all other connections with the brand (Jooste et al., 2012). Brand awareness leads to a better understanding of the brand and its offerings, which in turn leads to greater brand recall and recognition, resulting in more favourable brand associations (Aaker, 1996). When consumers are aware of a brand, they are more likely to form attitudes and beliefs about it, which contribute to them becoming repeat customers (Erdem & Swait, 2004). Brand awareness plays a crucial role in the creation and maintenance of brand equity. It is the first step in the process of building a positive brand image and creating a lasting impression in the minds of consumers (Keller, 2013). Several authors (Hyun, Park, Hawkins, & Kim, 2022; Yoo et al., 2000; Berry, 2000; Kim & Hyun, 2011) indicate that there is a positive relationship between brand awareness and consumer-based brand equity.

Perceived Quality

Perceived quality may be defined the consumer's overall evaluation regarding the brand’s performance, reliability, functionality and superiority, regardless of its objective or actual quality (Kotler & Keller, 2016, Baalbaki & Guzmán, 2016; Keller, 2013; Chi, Yeh & Yang, 2009). Consumer perceptions regarding the quality of a brand impact brand preference as well as the brand’s equity (Gill & Dawra, 2010). Consumers will be more willing to purchase a brand that is considered as the top brand in a product category based on the quality assurance. Consequently, higher quality brands can often charge premium prices based on the higher value attached to the brand (Dibb, Simkin, Pride & Ferrell, 2012). Perceived quality has been found to have a significant impact on consumer decision-making and brand loyalty. Consumers are often willing to pay a premium price for products or services that they perceive to be of high quality, as they associate high quality with greater value and benefits (Chen et al. 2021; Šugrová, Šedík, Kubelaková & Svetlíková, 2017). Moreover, perceived quality can also have an impact on a consumer's level of satisfaction and likelihood of repeat purchase behaviour. Brands that are consistently perceived to be of high quality are more likely to be associated with positive attributes and values, which can result in increased consumer trust and loyalty (Aaker, 1996). Perceived quality is a critical factor that should be carefully managed and cultivated by companies, as it is considered one of the key drivers of consumer-based brand equity.

Brand Loyalty

Brand loyalty refers to a consumer's willingness or preference to repeatedly purchase the same brand (Jooste et al., 2012; Lamb et al., 2013). It is considered a central component of brand equity (Aaker, 1996; Moisescu, 2007) and the ultimate consumer learning outcome for a company (Schiffman et al., 2010). Tong and Hawley (2009) concur that brand loyalty is a critical dimension of brand equity. Loyal consumers, who frequently return to make purchases, are highly valuable to a company. Jooste et al. (2012) argue that retaining current customers is more cost-effective than acquiring new ones. The benefits of brand loyalty are numerous and can have a substantial impact on a company's financial performance. Research has shown that loyal customers are more likely to make repeat purchases, purchase additional products and services, and recommend the brand to others (Schiffman et al., 2010). These actions can result in increased sales and reduced marketing costs, as loyal customers effectively serve as ambassadors for the brand. Moreover, brand loyalty can also enhance brand image and reputation. Loyal customers are more likely to have positive perceptions of the brand, which can lead to improved brand recognition and favourability (Jooste et al., 2012). Meeting or exceeding consumer expectations is crucial for creating brand loyalty (Keller, 2013). A consumer whose expectations are met will consistently return to the company, ultimately leading to brand loyalty. However, there is often a discrepancy between a consumer's expectations and a company's understanding of those expectations (Wilson et al., 2012). To ensure consumer satisfaction and foster brand loyalty, companies must strive to close this gap.

Brand Associations

Brand associations may be defined as “all brand-related thoughts, feelings, perceptions, images, experiences, beliefs, attitudes, and so on” that the consumer attaches to a brand (Kotler & Keller, 2012). According to Chen (2001), brand associations stem from the connection between two nodes in the consumer's mind. Essentially, consumers associate certain memories with a brand, thereby forming distinct brand associations (Fayrene & Lee, 2011). Keller (2013) highlights the importance of the strength, favourability and uniqueness of all the brand associations as a differential response that constitutes brand equity. Brand associations shape the perceptions and attitudes of consumers towards a particular brand by creating positive associations (Aaker, 1997). Brands can enhance their image, establish a unique identity, and increase consumer loyalty through strategic marketing activities to instil specific brand associations (Chatzipanagiotou, Christodoulides & Veloutsou, 2019). The strength, favourability, and uniqueness of brand associations serve as crucial differential factors that contribute to the formation of brand equity. These attributes of brand associations generate a distinctive response from consumers, thereby elevating the value and worth of a brand, and providing a foundational basis for brand equity (Keller, 1993). Hence, the prominence of brand associations in the determination of consumer-based brand equity underscores their essential significance in the marketing of brands.

2.4. Purchase Intention

The consumer's intention to purchase is defined as the initiative taken by the consumer to acquire a product or service from a specific brand (Sharma, Dwivedi, Arya & Siddiqui, 2021). Consumer-based brand equity has a significant impact on consumer purchase intention, and it can be argued that higher brand equity results in higher levels of purchase intention. Brand equity is essentially the value a brand adds to a product, and it represents the worth that a consumer perceives in a brand over and above its functional attributes (Moreira, Fortes & Santiago 2017; Kotler & Keller, 2016). Brand equity can increase consumer willingness to purchase a product due to its perceived added value, and it can also impact the price that a consumer is willing to pay for the product (Arya, Paul & Sethi, 2022; Erdem & Swait, 2004). Consumers who have favourable associations with a brand are more likely to have trust and confidence in the brand and its offerings, which in turn leads to higher levels of purchase intention (Aaker, 1996). Furthermore, brand equity also affects the consumer's choice of products by creating an advantage over competitors and increasing the brand's salience in the minds of consumers (Kapferer, 2012). Brands with high brand equity are more easily remembered by consumers, and they are more likely to be considered in future purchase decisions (Kotler & Keller, 2016).

2.5. Hypotheses

Based on the literature review, the following hypotheses were tested in this study:

H1: Brand awareness has a positive statistically significant influence on purchase intentions of WAT brands.

H2: Brand association has a positive statistically significant influence on purchase intentions of WAT brands.

H3: Perceived quality has a positive statistically significant influence on purchase intentions of WAT brands.

H4: Brand loyalty has a positive statistically significant influence on purchase intentions of WAT brands.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Participants and Procedures

The study’s target population comprised adult consumers aged between 18 and 56 years in 2022, residing in South Africa. A sample of 500 was drawn from a South African computer-administered online survey provider with 40 000 panellists. The provider adheres to ethical standards and POPI Act regulations during the data gathering process. Data was gathered from general South African consumers aged 18-56 using a computer-administered online survey guided by a descriptive research design.

The electronic research instrument comprised a cover page containing the study’s information, specifically the scope of the topic, namely wearable activity trackers with its definition and an illustration to avoid confusion when responding to the items. The survey gathered demographic information, followed by a section regarding respondents’ background regarding wearable activity trackers and brand preferences. Based on their preferred brand, participants had to respond to specific scaled items on a six-point Likert scale, where 1=strongly disagree and 6=strongly agree. These scales were adapted from previously validated research and included the consumer-based brand equity dimensions: brand awareness, perceived quality, brand association and brand loyalty (Besharat, 2010; Yoo et al., 2000 and Cheung et al., 2020) as well as purchase intention (Grace & O’Cass, 2005; Besharat, 2010).

3.2. Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS and AMOS Version 27.0. Analysis techniques comprised a Mahalanobis distance test to remove any outliers, descriptive statistics, factor analysis and structural equation modelling.

4. Results Reporting

Using a research company to collect the data automatically ensures that the intended 500 responses were received. However, following the data cleaning process and performing a Mahalanobis Distance Test to eliminate multivariate outliers (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013), 487 cases (97.4% success rate) were viable for data analysis. The demographical data revealed more female respondents (51.1%) and most of the respondents resided in the Gauteng province (49.9%), with the dominating home language being English (39.8%), followed by IsiZulu (14.0%). All South Africa’s nine provinces and 11 official languages were represented to a varying degree.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Factor Analysis Results

Evidently in Table 1, based on a six-point Likert scale, this sample of South African consumers have a statistically significant high-quality perception (mean = 4.96 ± 0.87; p=0.000) of their preferred wearable activity tracker brand and are likely to purchase (mean = 5.04 ± 0.96; p=0.000) such a device in the near future. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted on the scaled items. The EFA (KMO = 0.959; Bartlett’s test of sphericity: p = 0.000) was conducted by means of a principal component analysis using Varimax rotation. Five factors were extracted based on priori criterion and explained 74.2% of the total variance. All items loaded as expected with acceptable factor loadings and Cronbach alpha (α) values above 0.8 as presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and EFA results

| Descriptive statistics | EFA | |||||

| Latent factors | Mean | Std. dev. | t-value | p-value | Factor loadings | a |

| Brand Awareness | 4.70 | ± .97 | 27.17 | 0.000 | 0.52 - 0.81 | 0.86 |

| Brand association | 4.90 | ± 0.91 | 33.78 | 0.000 | 0.52 - 0.75 | 0.90 |

| Perceived quality | 4.96 | ± 0.87 | 37.11 | 0.000 | 0.64 - 0.76 | 0.88 |

| Brand loyalty | 4.65 | ± 1.00 | 25.50 | 0.000 | 0.59 - 0.86 | 0.88 |

| Purchase intention | 5.04 | ± 0.96 | 35.31 | 0.000 | 0.68 - 0.73 | 0.91 |

4.2. Reliability, Validity and Structural Model

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted, and the results presented in Table 2 were determined by means of structural equation modelling (SEM). The measurement model had acceptable model fit (CMIN/DF=2.99; CFI=0.95; IFI=0.95; SRMR= 0.038; RMSEA = 0.064). Furthermore, the reliability of the measurement model was acceptable with CR values above 0.7. The standardised loading estimates (>0.50) and AVE values (>0.50) suggest the convergent validity, while all the HTMT ratios meet the conditions for discriminant validity (Henseler, Ringle & Sarstedt, 2015).

Table 2. Estimates for the measurement model and correlation analysis

| CFA | Correlation analysis | |||||||

| Latent factors | Standardised estimates | CR | AVE | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 |

| Brand Awareness | 0 0.72 - 0 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.60 | 1 | ||||

| Brand association | 0 0.73 - 0 0.81 | 0.90 | 0.59 | 0.86* | 1 | |||

| Perceived quality | 0 0.78 - 0 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.65 | 0.74* | 0.83* | 1 | ||

| Brand loyalty | 0 0.65 - 0 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.66 | 0.71* | 0.74* | 0.77* | 1 | |

| Purchase intention | 0 0.86 - 0 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.76* | 0.82* | 0.84* | 0.80* | 1 |

| Note: *p < .001 | ||||||||

| HTMT ratios | F1↔F2: 0.86 ; F1↔F3: 0.74 ; F1↔F4: 0.70 ; F1↔F5: 0.76 ; F2↔F3: 0.83 ; F2↔F4: 0.72 ; F2↔F5: 0.83 ; F3↔F4: 0.77 ; F3↔F5: 0.84 ; F4↔F5: 0.78 | |||||||

| Model fit indices | CMIN/DF=2.99; CFI=0.95; IFI=0.95; SRMR= 0.038; RMSEA = 0.064 | |||||||

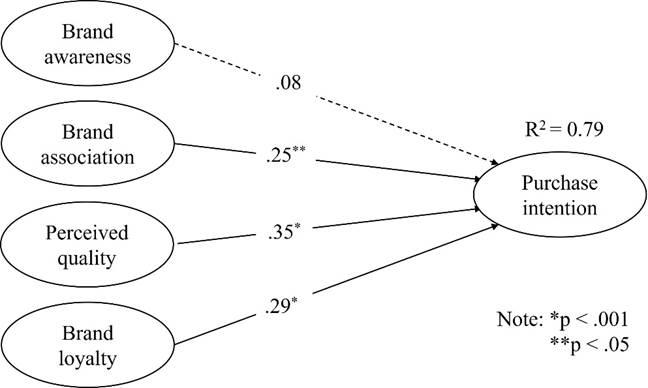

The structural model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Structural Model

The path coefficients of the structural model suggest that quality perception (β = 0.35, p < 0.001), brand loyalty (β = 0.29, p < 0.001) and brand association (β = 0.25, p < 0.05) are significant positive predictors of WAT purchase intention. As such, as shown in Table 3, H2, H3 and H4 were accepted. On the contrary, brand awareness was not proven to be a significant predictor of purchase intentions (β = 0.08, p > 0.05), therefore as shown in Table 3, H1 was rejected. A squared multiple correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.79 explains 79 percent of the variance in their purchase intention of Wearable activity tracker brands. Moreover, the fit indices remained unchanged, once again indicating good model fit.

Table 3. Outcome of the hypotheses testing

| Hypotheses | Paths | Standardised β | t-values | p-values | Outcome |

| H1 | Brand Awareness àPurchase intention | 0.0819 | 1.1094 | 0.2673 | Reject |

| H2 | Brand association àPurchase intention | 0.2539 | 2.8356 | 0.0046** | Accept |

| H3 | Perceived quality àPurchase intention | 0.3473 | 5.0317 | 0.0000* | Accept |

| H4 | Brand loyalty àPurchase intention | 0.2856 | 5.3513 | 0.0000* | Accept |

| Note: **p<0.05; *p<0.001 | |||||

5. Discussion and Conclusion

The consumer-based brand equity dimensions of quality perceptions, brand loyalty and brand associations are predictors WAT purchase intention among South African consumers. When consumers perceive a WAT brand to have high quality products, they are more likely to have a positive attitude towards the brand, which in turn leads to increased purchase intention. Furthermore, consumers who are loyal to a WAT brand are more likely to remain loyal in the future and make repeated purchases. This is because brand loyalty creates a sense of trust and confidence in the brand, which can lead to greater satisfaction and a stronger emotional connection with the brand. Finally, brand associations that consumers have with a WAT brand, also play a significant role in driving purchase intention. Positive brand associations can create a favourable image of the brand in the minds of consumers and increase the likelihood of future purchases. These findings echo those from studies who explored the factors influencing the purchase intention of wearable technology (Debnath et al., 2018; Ramkumar & Liang, 2020; Liao et al., 2021; Rahman et al., 2022).

6.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

The findings of this study have several theoretical and managerial implications. This study is among the first to investigate the influence of consumer-based brand equity in the context of wearable technology adoption. These results enable WAT brands to optimise their marketing strategy and identify areas of improvement to boost their sales and market share in South Africa. WAT brands require a dedicated focus on enhancing quality perception, build strong brand loyalty, and create positive brand associations in order to succeed in the market. By implementing such strategies, these brands can establish customer attraction and retention, promote brand recognition, and secure sustained success in the market.

Consumer-based brand equity plays a critical role in the purchase intention of WAT brands. Quality perception, brand loyalty, and brand associations are all critical drivers of purchase intention. WAT brands need to focus on delivering high-quality products that meet the expectations and needs of their customers. This can help to build a positive reputation for the brand and increase the likelihood that consumers will choose to purchase its products over those of its competitors. Brands can invest in research and development to continuously improve their products and ensure they are of the highest quality. Furthermore, building strong brand loyalty among customers is essential for WAT brands. This can help to ensure repeat purchases and increase the likelihood that customers will recommend the brand to others. Brands can create loyalty programs and offer incentives for customers to continue using their products. Additionally, companies can focus on creating an excellent customer experience to encourage customers to remain loyal to the brand. WAT brands need to develop positive brand associations in the minds of consumers. This can be achieved through targeted marketing and advertising campaigns that emphasize the brand's strengths and benefits. Brands can also focus on building relationships with customers through social media and other online channels to further strengthen their brand associations.

6.2. Limitations and Future Directions of Research

The limitations to the study include the restricted sample size and exclusive reliance on interview-based data collection. The inclusion of a broader sample paired with alternative data collection methods could have contributed to the acquisition of more comprehensive and diverse data. Future research should include an evenly distributed sample of different types of participants namely: teaching professionals, administrators, and players from all parts of South Africa. Future studies should also consider using a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative interviews with quantitative questionnaires for comprehensive insights. Furthermore, longitudinal studies can examine the long-term effects and changes that occur in the context of wearable activity tracker brands and their perceived equity.

---

Author Contributions: Re-an Müller: Conceptualization, Methodology, Statistical analysis, Writing- Original draft preparation. Chantel Muller: Data curation, Data cleaning, Validation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Acknowledgements: We extend our gratitude to the Faculty of Economic Management Sciences at North-West University and the WorkWell Research entity for their invaluable support in providing resources for this study.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest: Theauthors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

---

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The views, statements, opinions, data and information presented in all publications belong exclusively to the respective Author/s and Contributor/s, and not to Sprint Investify, the journal, and/or the editorial team. Hence, the publisher and editors disclaim responsibility for any harm and/or injury to individuals or property arising from the ideas, methodologies, propositions, instructions, or products mentioned in this content.

References

- Aaker, D.A., 1996. Measuring brand equity across products and markets. California management review, 38(3), pp.102-120

- Aggarwal, S.A., Rao, V.R. and Popli, S., 2013. Measuring consumer-based brand equity for Indian business schools. Journal of marketing for higher education, 23(2), pp.175-203.

- Ambler, T., 1992. Need-to-Know-Marketing. Century Business, London.

- Arya, V., Paul, J. and Sethi, D., 2022. Like it or not! Brand communication on social networking sites triggers consumer‐based brand equity. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 46(4), pp.1381-1398.

- Baalbaki, S. and Guzmán, F., 2016. A consumer-perceived consumer-based brand equity scale. Journal of Brand Management, 23, pp.229-251.

- Besharat, A., 2010. How co-branding versus brand extensions drive consumers' evaluations of new products: A brand equity approach. Industrial Marketing Management, 39, pp.1240–1249.

- Business Tech., 2018. South Africa expected to be the next big market for smartwatches and fitness trackers. [online] Available at: https://businesstech.co.za/news/mobile/243043/south-africaexpected-to-be-the-next-big-market-for-smartwatches-and-fitness-trackers/

- Cant, M.C. and Van Heerden, C.H., 2013. Marketing Management, A South African perspective. Cape Town, South Africa: Juta.

- Chatzipanagiotou, K., Christodoulides, G. and Veloutsou, C., 2019. Managing the consumer-based brand equity process: A cross-cultural perspective. International Business Review, 28(2), pp.328-343.

- Chen A.C.H., 2001. Using free association to examine the relationship between the characteristic of brand association and brand equity. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 10(7), pp.439-451.

- Chen, L., Halepoto, H., Liu, C., Kumari, N., Yan, X., Du, Q. and Memon, H., 2021. Relationship analysis among apparel brand image, self-congruity, and consumers’ purchase intention. Sustainability, 13(22), pp.12770.

- Cheung, M.L., Pires, G. and Rosenberger, P.J., 2020. Exploring synergetic effects of social-media communication and distribution strategy on consumer-based Brand equity. Asian Journal of Business Research, 10(1), pp. 126-149.

- Chung, T.W., Jang, H.M. and Han, J.K., 2013. Financial-based brand value of Incheon international airport. The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics, 29(2), pp.267-286.

- Corporate Finance Institute., 2021. What is Brand Equity? [online] Available at: https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/other/brand-equity/

- Dandu, R., 2015. What Is Branding and Why Is It Important for Your Business? https://www.brandingmag.com/2015/10/14/what-is-branding-and-why-is-it-important-for-your-business/ Accessed 26 May 2021.

- Dibb, S., Simkin, L., Pride, W.M. and Ferrell, O.C., 2012. Marketing: concepts and strategies. 6th ed. Andover: South-Western Cengage Learning.

- Dranove, D. and Jin, G.Z., 2010. Quality disclosure and certification: Theory and practice. No. w15644. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Du Toit, M. and Erdis, C., eds., 2013. Fundamentals of branding. Cape Town, South Africa: Juta.

- Erdem, T., & Swait, J., 2004. Consumer and brand evaluations as drivers of brand equity: A dynamic capabilities framework. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 21(3), pp.299-316.

- Fearless., 2019. People Buy Brands, Not Products. Here's Why. [online] Available at: https://fearless.com.au/our-blog/people-buy-brands-not-products-heres-why

- Gill, M.S. and Dawra, J., 2010. Evaluating Aaker's sources of brand equity and the mediating role of brand image. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 18(3), pp.189-198.

- Grace, D. and O’Cass, A., 2005. Service branding: consumer verdicts on service brands. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 12, pp.125–139. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2004.05.002

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M. and Sarstedt, M., 2015. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-based Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), pp.115-135.

- Hyun, H., Park, J., Hawkins, M.A. and Kim, D., 2022. How luxury brands build customer-based brand equity through phygital experience. Journal of Strategic Marketing, pp.1-25.

- Jobber, D., 2010. Principles of Marketing 6th ed. McGraw-Hill.

- Jooste, C.J., Strydom, J.W., Berndt, A. and Du Plessis, P.J., 2012. Applied strategic marketing. 4th ed. Cape Town, South Africa: Pearson.

- Kapferer, J.N., 2012. The new strategic brand management: Advanced insights and strategic thinking. Kogan Page Publishers.

- Keller, K. L., 2013. Strategic brand management: building, measuring, and managing brand equity. Upper Saddle River, USA: Pearson Education.

- Keller, K.L. and Lehmann, D.R., 2006. Brands and branding: Research findings and future priorities. Marketing Science, 25(6), pp.740-759.

- Kim, E-J., Kim, S-H. and Lee, Y., 2019. The effects of brand hearsay on brand trust and brand attitudes. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(7), pp.765–784.

- Klopper, H.B. and North, E., 2011. Brand management. Cape Town, South Africa: Pearson Education.

- Kotler, P. and Keller, K., 2012. Marketing Management. 14th Edition. Upper Saddle River, USA: Pearson Education.

- Lamb, C.W., Hair, J.F., McDaniel, C., Boshoff, C., Terblanche, N., Elliott, R. and Klopper, H. B., 2013. Marketing. 4th Ed. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press.

- Moreira, A. C., Fortes, N., & Santiago, R., 2017. Influence of sensory stimuli on brand experience, brand equity and purchase intention. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 18(1), 68–83. https://doi.org/10.3846/16111699.2016.1252793

- Muller, C., 2019. Generation Y students’ attitude towards and intention to use activity-tracking devices. Doctoral Thesis. Vanderbijlpark: North-West University.

- P&S Market Research., 2018. Wearable fitness trackers market to reach $48.2 billion by 2023. [online] Available at: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2018/03/28/1454453/0/en/Wearable-Fitness-Trackers-Market-to-Reach-48-2-Billion-by-2023-P-S-Market-Research.html

- Phipps, M., Brace-Govan, J. and Jevons, C., 2010. The duality of political brand equity. European Journal of Marketing, 44(3/4), pp.496-514.

- Sharma, A., Dwivedi, Y.K., Arya, V. and Siddiqui, M.Q., 2021. Does SMS advertising still have relevance to increase consumer purchase intention? A hybrid PLS-SEM-neural network modelling approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 124, 106919.

- Srinivasan, S., Hsu, L. and Fournier, S., 2011. Branding and firm value., In Ganesan, S & Bharadwaj, S., eds., Handbook of Marketing and Finance, Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Stables, J., 2021. Best fitness tracker 2021: top picks for all budgets. [online] Available at: https://www.wareable.com/fitness-trackers/the-best-fitness-tracker

- Statista., 2020. Wearables South Africa. [online] Available at: https://www.statista.com/outlook/319/112/wearables/south-africa Accessed 8 June 2020.

- Statista., 2021. Wearables South Africa. [online] Available at: https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/eservices/fitness/wearables/south-africa

- Strizhakova, Y., Coulter, R.A. and Price, L.L., 2011. Branding in a global marketplace: The mediating effects of quality and self-identity brand signals. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 28(4), pp.342-351.

- Šugrová, M., Šedík, P., Kubelaková, A. and Svetlíková, V., 2017. Impact of the product quality on consumer satisfaction and corporate brand. Економiчний часопис-XXI, 165(5-6), pp.133-137.

- Tabachnick, B.G. & Fidell, L.S., 2013. Using multivariate statistics. 6th ed. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- The Economic Times., 2021. Definition of 'Brands'. [online] Available at: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/definition/brands Accessed 26 May 2021.

- Tong, X. and Hawley, J.M., 2009. Creating brand equity in the Chinese clothing market: the effect of selected marketing activities on brand equity dimensions. Journal of fashion marketing and management, 13(4), pp.566-581.

- Veloutsou, C., Christodoulides, G. and De Chernatony, L., 2013. A taxonomy of measures for consumer-based brand equity: drawing on the views of managers in Europe. Journal of product and brand management, 22(3), pp.238-248.

- Walker-Todd, A. 2021. Best Fitness Tracker 2021. [online] Available at: https://www.techadvisor.com/test-centre/wearable-tech/best-fitness-tracker-3498368/ Accessed 9 June 2021.

- Wood, L., 2000. Brands and brand equity: definition and management. Management decision, 38(9), pp.662-669.

- Yoo, B., Donthu, N., & Lee, S., 2000. An examination of selected marketing mix elements and brand equity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(2), pp.195-211.

Article Rights and License

© 2024 The Authors. Published by Sprint Investify. ISSN 2359-7712. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.