Keywordsexport items exports framework National export strategy portal South Africa

JEL Classification M30

Full Article

1. Introduction

With the importance of exports to economic growth acknowledged by numerous authors over the years (Shihab and Abdul-Khaliq, 2014; United States Department of Commerce, 2014; Cross, 2016; Ali, 2017; Mabuyane, 2019), it makes sense for governments of countries to take proactive steps to promote exports in whatever way possible as this should have a direct and positive impact on the country’s economic output, growth and development (Belloc and Di Maio, 2011; United States Department of Commerce, 2014). The activities and policies to promote the growth of a country’s exports are defined by Belloc and Di Maio (2011) as a single concept, namely ‘export promotion’ (see also Cuyvers and Viviers (2012) where they further describe export promotion). Olarreaga, Lederman and Payton (2010), identified 103 countries around the world with national export promotion agencies and programmes, including South Africa.

National export promotion efforts come in various forms. Financial export promotion includes government-provided subsidies, incentives, drawbacks, export credits, export-credit guarantees, free trade zones, and other similar financial offerings and services. Marketing/administrative export promotion (which may be provided by the public or private sector) includes providing training and seminars on exporting, running mentorship programmes for exporters, promoting exports via a global network of foreign-based trade representatives, providing telephone and face-to-face advice to exporters, recognising successful exporters by way of export awards, providing export incentives, helping with trade dispute settlement, providing export and credit finance, facilitating a clearinghouse for overseas trade enquiries, and, not least of all, providing reference, how-to and networking information to exporters (Cuyvers and Viviers, 2012; International Trade Centre [ITC], 2004; Lahtinen and Rannikko, 2018; Lederman, Olarreaga and Payton, 2009; Yuzawa, 2012). ‘Export promotion’ is sometimes included under the title of ‘trade promotion’ (a broader term that includes both export and import promotion)

One way of facilitating the promotion of exports, is to use online technologies to create a national export portal (NEP) or system from where exporters can obtain the information they need and seek out relevant support providers from within the local export support community. Chuvakin (2007), in his doctoral thesis, defines a portal as “…a term, generally synonymous with a gateway [to information], for a World Wide Web (WWW) site that either proposes to be a major starting site for users when they get connected to the web, or that users tend to visit as an anchor site.” In other words, a portal serves as a ‘one-stop-shop’ or ‘single-window’ to greater width and depth of information about a particular topic or industry than might otherwise be available through other means (Double, 2005). An export portal can thus be described as a starting website for individuals from the export community who are looking for more information about exports and exporting. The recent “Study on best practices on national export promotion activities” undertaken by the European Economic and Social Committee (Lahtinen and Rannikko, 2018), highlights the value of portals and repeatedly refers to examples among export promotion agencies of the provision of export information through online means.

Several countries around the world, including the United States of America (USA), Canada, the United Kingdom (UK), Australia, New Zealand and Malaysia, have already developed national export information portals with the aim of assisting their own export communities to succeed in exports. South Africa, however, is still without such a portal at this stage, although, the Department of Trade and Industry did investigate developing such a portal a number of years ago but the project never came to fruition (Audier, 2007; Gouws, 2013).

In 2016, the DTI announced its Integrated National Export Strategy (the INES, also referred to as Export 2030) (DTI, 2016). The INES identifies a national export information system (analogous to the NEP that this article discusses) as a key element of the country’s proposed export promotion efforts (Gouws, 2013; Gouws and Moore, 2012). However, to date, an NEP or any other similar online export information system has not been developed by the DTI.

With an export portal having been identified as an important export promotion channel and tool, the question arises as to what information and resources the portal should contain. This study attempts to gain insight into the information and resources that should populate the portal, and proposes a framework for the establishment of an NEP for the country. As the study argues that information is a key contributor to success in exporting, an NEP should prove of value to the local export community by serving as an easy-to-access ‘gateway’ to information, as well as to other resources (such as networks) that exporters can use in their exporting endeavours. By taking the initiative to research the requirements of such a portal, it is hoped that the study would contribute to the development of the framework for a proposed NEP that would, in turn, ultimately help promote future export not only in South Africa, but globally.

1.1. Study Objectives

The main objective of this study was to develop a framework outlining the specific information, as well as the organisational structure which could then be used to develop and implement an NEP in South Africa specifically, but which could also be used as a basis for starting or redeveloping a similar portal in another country.

2. Study Methodology

A broad research approach was envisaged incorporating an extensive review of the literature examining (i) the nature and extent of the export environment in South Africa to determine what information about the export environment (including role players) should be incorporated in the proposed portal; (ii) the nature of the information required by exporters as far as the exporting process is concerned, while (iii) also reviewing 12 NEPs around the world to compliment the information already gathered. The portals reviewed comprised those of Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, Ireland, Jamaica, Kenya, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, Uganda, the UK and the USA. These portal web addresses are provided in the reference section. In addition, the ITC’s Trade Portal Tool (2003), Cateora, Graham and Gilly’s Country Notebook (2019), and the export promotion efforts of a host of local organised commerce organisations were also examined as part of the literature review.

Clearly, the literature is replete with academic texts and articles, as well as practical guides on export information, and, as the focus of this article is more about presenting a framework for an NEP, this extensive literature will therefore not be repeated here. What the article does wish to highlight is the empirical research undertaken by the authors in seeking to capture the views of exporters, as well as respondents from the export support community, as to the how this information might best be organised and delivered to the local exporter community via an online NEP. As South Africa does not yet have an NEP, it was felt that this insight could be of value to the country to develop the proposed NEP.

The purpose of the literature survey and review of existing portals was to identify the information items that should be included in the proposed NEP. In addition, the literature survey provided some understanding of the use of information (particularly online information) by exporters. It is believed that their use of information would dictate the way the portal is ultimately organised and developed.

A multi- and mixed-method approach was subsequently adopted involving the following tasks:

- A series of in-depth personal interviews with 30 purposively-selected respondents from the exporter community around the country with the purpose of reviewing, expanding on and revising the list of export information items identified from the literature survey.

- A card-sorting exercise in which the same 30 respondents were also asked to sort these information items into logical categories (that would ultimately represent the portal structure) using a card-sorting methodology, combined with software from OptimalSort.

- The standardisation of the card-sorting data with the input from an expert group comprising five individuals.

- A series of in-depth personal interviews with 20 purposively-selected respondents from the export support community (e.g. government, banks, export councils, compliance assurers, credit providers, freight forwarders, etc.) to solicit their insight into the suitability of the framework. The export support community, it was felt, often plays a pivotal role in the export process and their insight within the context of this study was considered vital in developing an effective NEP.

- Finally, once the interviews were completed, the revised framework for the proposed NEP was presented to the same database of exporters used for the earlier INES survey undertaken by the DTI. This was done through an online survey. Two thousand seven hundred and forty-four (2 744) firms from the exporter community were emailed an online questionnaire using Lime Survey. The survey included Likert-type questions and other descriptive measures to obtain a rating of respondents’ views of the importance of the information topics, subtopics and items uncovered from the earlier research. One hundred and seventy-one exporters (171, 6.2% of the sample) completed the survey. Respondents were also surveyed on their views about the importance of the proposed portal generally and on a variety of other issues pertaining to the implementation of the proposed NEP.

During this research process use was made of an external trade expert to provide oversight over, as well as objectivity on the transparency and validity to an otherwise subjective process.

3. Findings

The multi- and mixed-method research approaches adopted in this study led to a portal framework being synthesised from the research. The literature identified 149 information items for the proposed portal. Following the survey of the export community, these 149 information items were ultimately clustered under 45 different subtopics, after which the subtopics were grouped into seven major topics according to the mean importance rating scores allocated by respondents to the information items and topics in the survey. The resultant framework based on these findings is discussed in more detail in the next section.

4. Discussion

The findings led to the development of a framework which is outlined in point 4.1 below.

4.1. Framework of Information Topics to be used as a Structure for the Proposed NEP

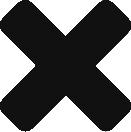

The proposed framework that can be used as a structure for an NEP is presented in figure 1 below. The findings point not only to seven primary topics, but also to numerous secondary subtopics per primary topic (ranging from four to nine subtopics), as depicted in figure 1. In figure 1, the primary topics are presented in the rectangular blocks, while the secondary subtopics associated with each primary topic are listed below the topic in question. The importance ratings of the topics and subtopics were obtained from the online survey of exporters and have also been included in figure 1.

Figure 1. Proposed framework for the NEP

Source: Author’s own compilation

4.2 Importance Ratings for the Information Topics

As part of the online exporter survey, respondents were asked to rate the importance of the various topics and subtopics. The conclusion based on these findings is that there is a preferred organisational structure that can be applied to the framework of topics and subtopics. This hierarchy of importance is already reflected in figure 1 starting with the ‘financial’ topics (numbered as 1), through to the ‘general information’ topic (numbered as 7). Under each topic, the subtopics have also been ordered according to their perceived importance as reflected in the findings. It is also suggested that in developing a NEP, that starting content should be prioritised according to these importance ratings. By ‘starting content’ is meant the content that will be most visible to users. Over time the information topics and subtopics can be expanded on and ‘fine-tuned’ according to usage and user feedback such as reviews, ratings and online up- and down-voting.

4.3 The Proposed NEP is Seen as Important

The above conclusion can be drawn with some certainty considering the fact that 89.2% of respondents indicated that they perceived the proposed NEP to be important for South Africa., Even if only the ‘very important’ ratings are considered (i.e. excluding ‘important’), then the findings reveal that 63.7% of respondents perceived the proposed NEP to be very important for South Africa.

The respondents from the exporter community were also asked to comment in an open-ended question about the role and importance of the proposed portal. The comments by exporters generally supported the positive ratings awarded by respondents in respect of the importance of the proposed portal.

Although the need for the proposed portal had already been identified by the INES as mentioned earlier, the value of reconfirming the importance of and need for the portal underscores the key role the proposed export portal is expected to play in the South African context, and this conclusion is expected to drive the implementation of the portal. These facts can be used to convince the authorities who will ultimately be responsible for initiating, deciding on and implementing the proposed NEP in South Africa (i.e. the DTI), to make their decision and to undertake this venture sooner rather than later.

4.4 The Proposed NEP should be Owned and Run by a Public-Private Partnership

One of the questions put to respondents from the exporter community was to ask them who should run the proposed portal. Of the seven options respondents could choose from, almost a third of the respondents (30.3%) opted for a public–private partnership. A further fifth of the respondents (20.0%) felt that organised commerce should run the proposed portal, with only 18.7% choosing the DTI. The DTI is currently the ‘mother organisation’ for export promotion in South Africa and this is true of many other countries. For this reason, the DTI was specifically named in the survey. The private sector received 17.4% support, while industry associations received 11.6% of the support.

A closer examination of these findings reveal that, while 20% of respondents opted for a government-run portal (18.7% support for the DTI, suggesting that 1.3% of the respondents felt that some other government department and not the DTI should run the portal), an overwhelming 80% of the respondents felt that it should not solely be run by government. As alluded to in the preceding paragraph, the preferred alternative was a public–private partnership, followed by organised commerce, the private sector, or a sectoral/industry partnership (such as an export council or industry association).

The commentary from respondents was revealing in that, while there were numerous positive comments about the need for the portal, the negative comments included comments such as:

- “The country needs a portal, but it should not be implemented by government”.

- “… government does not understand its own laws and regulations, so portal [sic] will have zero benefit”.

- “The portal is very important, but the problem in SA is that government is creating too much bureaucracy for businesses and they also do not ‘talk-the-talk’ with assistance”.

What was clear from these comments was that respondents saw a difference between ‘owning’ the portal and ‘running’ the portal. By ‘owning’ is meant that the owner has oversight over the strategic direction of the portal but is not necessarily involved in the day-to-day running of the portal (which should be in the hands of the private sector; hence, a public–private partnership).

The export support community was asked a similar question, but the focus was on who should ‘own’ the proposed portal. Most respondents (60%) felt that it should be government-owned, but privately run (echoing the sentiment of exporters), with only 20% supporting a government-owned and government-run portal (the remainder – also 20% – supported a privately owned and privately-run portal). Because of the small non-random sample size (n=20) these figures cannot be considered statistically meaningful, but the figures do support the views held by the exporter community, which was discussed in the paragraph above.

These findings lead to the conclusion that the proposed NEP should be owned by the DTI, who should give credibility and legitimacy to the proposed portal as they are the recognised export promotion authority in South Africa, but that the day-to-day running of the portal should be in the hands of the private sector (i.e., emphasising the public–private partnership view supported by respondents

4.5 The Proposed NEP should be Developed on a Hybrid Model

The findings suggest that the most support amongst respondents from the exporter community (41.3%) was for an NEP, followed closely by a hybrid model (33.5%).A hybrid model is one that includes national, as well as regional and sector perspectives. Just over a fifth of respondents (22.9%) supported the idea of industry-based portals, while very few respondents (2.6%) supported regional portals. The strong support for a national portal suggests that the portal should be entirely national (i.e. with little or no focus on industry and/or regional needs) or, if it is developed as a hybrid model, that the focus should be predominately national, but with considerable support for industry (and even regional) needs. If one compares the desire for an industry portal versus a regional portal (22.9% vs. 2.6%), one can see that satisfying industry needs are more important than satisfying regional needs.

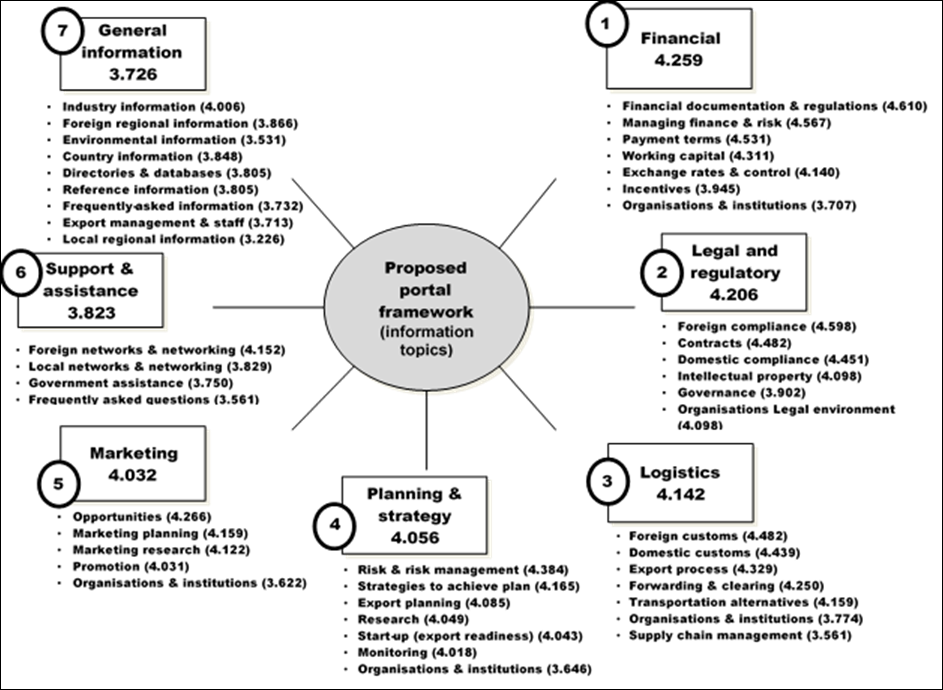

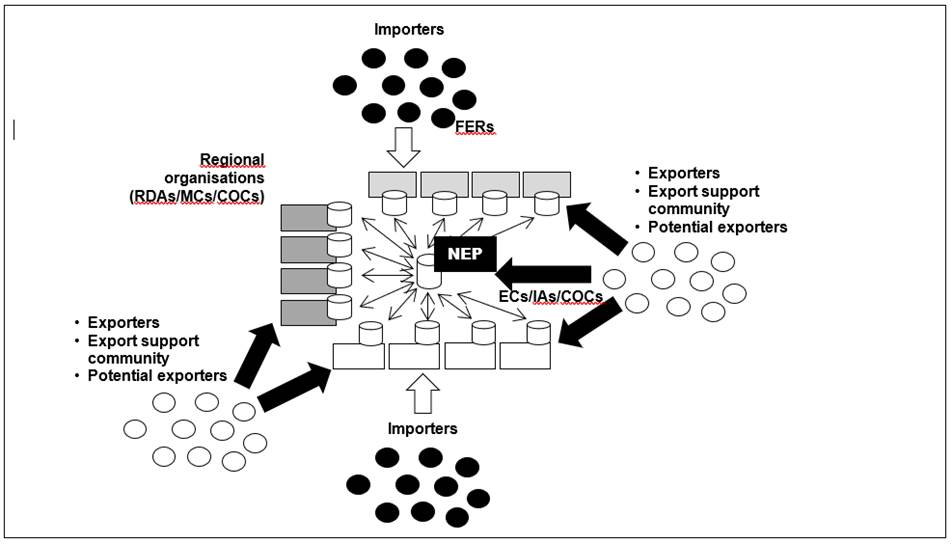

Although the largest support was for a national portal (41.3%), a hybrid portal arguably makes better sense as it makes it possible to address national needs, industry needs and even regional needs within a single portal framework. The idea of a hybrid model was discussed during the series of interviews with the export support community, and a model was developed conceptually based on the feedback received from interview to interview. Unfortunately, given the graphic and composite nature of the model, it was not possible to present the model to respondents from the exporter community in the somewhat restricted online survey in order to get their response to the model. The reality of web technology is, however, that a portal can, be developed in a way that appears outwardly to be predominately national, yet still meets industry and regional needs, that is, a hybrid model. It is proposed that a hybrid model is the preferred approach as it addresses all the needs of respondents. The proposed hybrid model is outlined in figure.2 below, a central database (or more likely a system of databases) would contain a spectrum of information that would service the NEP – primarily either company or contact information, statistical information or textual/web content.

Figure 2. Industry and regional integration with portal

Notes: * In the case of regional information, the COC would a regional or city COC, while in the case of industry information, the COC would be an industry COC. EC=export council; IA=industry association; COC=chamber of commerce; RDA=regional development agency; FER= foreign economic representative; MC=metropolitan councils

Source: Authors’ own creation

4.6 The Proposed NEP should be up to Date, Easy To Use, Comprehensive, and Detailed

One of the key questions put to respondents from the online survey of exporters was to ask each of them to identify two critical success factors for the proposed portal. Overall, the three critical success factors receiving the most support are:

- The content needs to be up to date;

- the portal should be easy to use; and

- the content should be comprehensive and detailed.

While there were other critical success factors identified, the above three critical success factors stood out with the first of these being the most important by far. Thus, it can be concluded that proposed NEP should be up to date, easy to use, comprehensive and detailed if it is to succeed.

4.7 The Export Community Knows and Understands Online Business Well Enough to Use the Proposed NEP

The findings point to respondents being au fait with online business, with 71.9% of respondents rating themselves either ‘very able’ to deal with online business (27.5%) or ‘able’ (44.4%). None of the respondents considered themselves not able to work online. A similar, question was put to the export support community and three quarters (75%) of the small non-random sample considered themselves to be experienced online users. Based on these findings, it can be concluded that the export community (i.e. comprising the exporter community and the export support community) were experienced enough to use the proposed NEP. Put another way, the technical skills of potential users of the proposed portal should not be a stumbling block to its use or success. However, based on comments made by respondents, it is suggested that the proposed portal, once developed, should include a self-help or self-learning component.

4.8 The Proposed NEP should not include a Local Trading Hub

Two questions as to whether a trading hub is required in South Africa and whether the hub should be included as part of the portal, were put to the respondents. The findings suggested indecision on the part of respondents. Half (50%) of the respondents felt that a trading hub was not needed in South Africa, and, the other 50% felt that it was. Of the respondents who felt a portal was required, only 40% felt it should be included as part of the proposed export portal. It is therefore suggested that a trading hub should probably not be built into or incorporated with the proposed portal. This conclusion is supported by the fact that none of the researched NEPs currently have a built-in trading hub as part of the portal. The reason for this could be because a trade hub and an information portal are essentially two very different entities with different target audiences (one is about information and the other about buying and selling). Said trading hub and the information portal may be related, but it is proposed that they need to be run separately, albeit linked.

4.9 Ensure that the NEP is Dynamic and User-Driven

Another key success factor for the proposed portal as identified by respondents was that the portal should be dynamic as well as user driven. While the concept of dynamism is closely related to the idea that the portal should be well-maintained, a dynamic site is one that changes regularly (sometimes from an appearance perspective and not necessarily from an update perspective). In other words, the focus of the site may change in appearance from day-to-day, or even from user-to-user. On one day the focus may be on logistics, while on another day the focus may be on financing exports. Similarly, depending on how the site is developed, a user that is recognised as being a start-up exporter may receive different information than an exporter who is recognised as being an experienced exporter (the two exporters may have indicated their experience when they originally registered on the portal). The portal would draw on its database of information and present the relevant information given certain circumstances (e.g. the experience of users or perhaps given their most recent search activities on the portal).

The focus of a dynamic site is to provide relevant information to users with the understanding that users are different and have different information needs. This links to the second point, namely that the portal should be user driven. The portal should be developed in such a way that it can track a user’s needs either on the information they provide upon registration, in answer to survey questions, or based on their onsite behaviour as tracked by the server software.

Consequently, it is recommended that the site be developed in such a way that it provides dynamic and ever-changing information depending on users’ needs. The site should be user-centric, with, users’ needs being determined through, sign-up information, surveys, and discussion forums, while also tracking users’ online browsing/searching behaviour to provide further clues as to their information needs.

4.10 The Proposed NEP should have a Learning Role and an Informational Role

Although the proposed portal was originally seen to be an information portal for exporters, and although the export experience of respondents appeared to be reasonably good, the need to constantly grow export knowledge amongst the export community as determined by the National Exporter Development Plan (NEDP) (especially amongst potential exporters not included in this study, as well as developing or inexperienced exporters), supports the idea of developing the proposed NEP as a learning portal in addition to an information portal. In addition, the findings, revealing that less experienced exporters considered the proposed portal as more needed than experienced exporters, support the view that a learning function would be beneficial to less experienced exporters. This should not be difficult to implement as information and learning are closely linked (i.e. learning is based on the assimilation, codification and application of information). Based on these findings, it is therefore concluded that the proposed NEP should have a learning role in addition to an information role.

4.11 The NEP should be run on a Public-Private Partnership Basis

Respondents were generally in agreement that the proposed portal, or at least the establishment of the proposed portal, should be driven by government (in the case of South Africa, the DTI). It is therefore recommended that the DTI support the establishment of a public-private partnership to run the proposed portal. Questions such as who should be part of the partnership and what their roles should be, still need to be clarified.

4.12 The NEP should not be Developed in Isolation

Notwithstanding the overwhelming support for the proposed NEP, the portal is not a panacea that will address all the country’s export development and promotion needs at once. A portal is only part of the total solution, and other solutions that will contribute to an improved export sector include, for example:

- Exporter training (as identified in the NEDP);

- a national vision as captured in the INES;

- continuation of the export marketing incentives; and

- export villages to bring the efforts of exporters within sectors to address global needs.

Several such solutions are discussed in the INES (Gouws 2013). It is therefore recommended that the proposed portal be seen part of a bigger solution and that the portal be developed and managed in a way that supports a comprehensive export promotion strategy.

4.13 The Proposed NEP Should Draw on an Include Existing Export Information Sources

The findings suggest that there are already existing sources of export information that respondents are using. It is therefore concluded that, in order to facilitate the speedy development and launch of the proposed NEP, the team selected to develop the proposed portal should draw on and include these existing information sources in the proposed NEP. Some of these sources are seen as more important than others, and more emphasis could be put into incorporating those sources seen as more important.

4.14 The NEP Should Establish a Network of Information Partners

In addition to using existing sources of export information, the proposed portal should develop a network of information partners to become part of the content creation for the portal. The information partners would comprise two main groups, namely corporates such as banks and freight forwarders, export advisors, insurance providers, courier companies, airlines and shipping lines, and individuals who write about specific topics about which they are knowledgeable. A leading bank or freight forwarder may be willing to write about the role of banking or freight forwarding in exports as long as they can share information about their own services with readers – it is a form of publicity for them. As far as individuals are concerned, there are many individuals who are experts about very specific topics, and they could be encouraged to share their expertise with exporters via the portal. Although a network of information partners will help in growing and improving the content on the portal, the network still needs to be managed and there may also be costs associated with this network (i.e. payment of freelance fees). However, this network can also assist in marketing the portal to the export community as each information provider encourages his/her contacts to use the portal.

Via the NEP (as depicted in figure 2) users would be able to access a wealth of general export information, as well as exporter information (e.g. contact and product details, industry information both local and foreign, regional information such as local support programmes, as well as contacts and foreign country information supplied by the foreign economic representatives). The NEP would serve as a ‘single window’ access to all this information. How the information is organised in the database would be of no concern or interest to exporters. All they would be concerned with is accessing the information they need as easily as possible.

It is quite possible that export councils and/or industry associations may also want to have their own ‘mini-industry portals’ and this can be done in the model as depicted in figure 2. Each export council or industry association or other industry-related organisation would have its own industry site to which the exporters in its sector can be linked. The exporter information would however be accessed from the central NEP server. In addition, both local and international industry information can be compiled and stored in a database for easy access by exporters or foreign buyers. Again, this information would be stored in the central NEP database. The owner of the industry site would contribute to maintaining the exporter database for the companies in their respective sectors. They would also contribute to adding relevant industry information to the content database housed with the NEP. In this way, owners of industry sites could have their own websites, but could draw on the relevant exporter and content information contained in the NEP and present that information as their own and integrated with their websites.

The owner of another industry could follow a similar path, while two organisations in the same industry could offer a similar path. Their various websites would appear different to their respective users with different branding and a different look and feel, but would draw on similar export information from the NEP. There would need to be strict administrative and security protocols in place to ensure that the information is not abused and that only those organisations who have entered the information may access the information (where this may be desirable).

In a similar way, the various regions could also have information from the NEP integrated with their respective sites. Thus, on one regional development agency (such as WESGRO [www.wesgro.co.za] in the Western Cape, one of nine provinces in South Africa), a local user (or even a foreign visitor) would be able to access a list of all the exporters in the Western Cape, including their company and product details. Users could also access export information pertinent to the region in question, so they might only be able to see those events and services available in the Western Cape (and not elsewhere). Certain information about events, such as overseas trade missions, overseas national trade pavilions, local and international industry expositions and training, could be made available to everyone. It would make no sense to keep a national industry fair in Johannesburg or an up-coming national trade mission to Bulgaria secret from exporters in the Western Cape. However, the Gauteng Growth Development Agency (GGDA) (Gauteng is another province in South Africa) may not want the rest of the country to know that they are planning a special event and this event would only be made available to firms that have been flagged as being linked or associated with the GGDA. Therefore, there would be information that is flagged as only local, while other information is flagged as local, national and/or international (i.e. you may want foreign companies to see the information as well – examples might include industry fairs in South Africa, outgoing missions, exporter information and export service providers). Exactly how this flagging is done would need to be carefully considered and the algorithms built into the portal and database, thereby controlling who has access to what.

Finally, the information gathered by the DTI’s foreign economic representatives (FERs) based at the embassies and consulates in various countries abroad should also be made available to exporters. Thus, if the FER in London compiles a marketing research report, such report would immediately be made available to all exporters who might be interested in the report. In addition, any trade leads or trade opportunities identified by the FER would also be sent to the relevant exporters in South Africa directly via the database. Thus, if there was a query for the supply of contemporary wooden furniture, for example, the query would be sent to those exporters registered on the database for that particular product, or product category.

In this proposed model, the NEP becomes a clearing house of information that is syndicated to various information intermediaries (in this regard, for instance, the export councils, industry associations, regional development agencies and metropolitan councils could also be seen as information intermediaries). Not only could these information intermediaries serve as a targeted outlet for export information (i.e. enabling their respective constituencies [i.e. exporters] to access relevant information as and when they require), but they could also assist in gathering and adding information to the portal. In this way, they would be both an outlet and inlet for information to and from the portal. These intermediaries could be described as ‘information partners’. They would take charge of gathering, filtering, editing and contributing relevant information to the NEP, and would also provide appropriate access to this information via their respective websites to their respective target audiences. In this way, the NEP would have tens or even hundreds of information partners that could assist in compiling and disseminating information. The partners benefit because the information is more complete than without the input from all the information partners and they can offer their clients a greater scope of export information, which, for all intents and purposes, appears as their information.

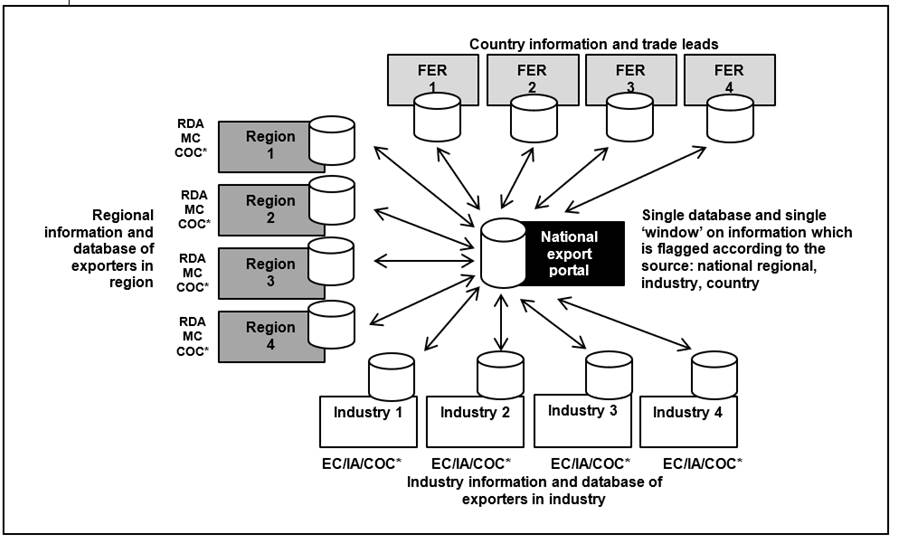

The ownership and management of the proposed portal would be linked to the underlying information framework. Drawing on the findings of exporters discussed earlier, it is proposed that the DTI would own the portal. However, it is further proposed that an advisory board comprising government, private sector, non-government and organised commerce representatives would set the strategic direction for the portal, and that a small private-sector team should run the portal on a day-to-day basis. This relationship is depicted in figure 3 below. Although the exact relationship would need to be decided on by all the parties involved, especially the DTI, it is proposed that the DTI should set very broad policies within their INES and may even document an NEP policy that dictates the portal’s vision, mission and objectives, as well as identifying the individuals and organisations involved in implementing the portal. The DTI would bring together all the key role players in export promotion for a planning workshop. Likely participants would include other government departments involved in exports, the export councils, the main chambers in the country, the rail operators, the South African Association of Freight Forwarders, leading industry associations, the main shipping lines, airlines, the main regional development agencies, the ports and harbours authorities, key role players from the export support community, selected exporters (perhaps recent export award winners as it would be impractical to invite all exporters), as well as any other organisations that could play a role in export promotion in the country.

In addition to the DTI, the workshop and its small executive, a small management team should be appointed to run the portal. A small team of approximately five persons should run the technical and content aspects of the portal ensuring that the content is updated daily and that the portal functions effectively and reaches the audience it is aimed at. Part of the task of the management team would be to promote the portal to its various audiences.

Figure 3. Ownership and management of portal

Source: Authors’ own creation

Finally, a significant benefit of the proposed model would be to provide multiple access routes to the portal for users. These users can be divided into four broad groups. These groups are exporters, the export support community, potential exporters, and others (e.g. students, journalists, researchers and government officials) who could access the portal via the websites of regional organisations such as metropolitan councils, local chambers of commerce and RDAs, including WESGRO, TIKZN and GGDA. The export portal is not aimed at importers, but it could be extended to serve foreign importers with the main aim of bringing them in touch with local suppliers. Bearing in mind that imports are the other side of the ‘trade coin’. If the portal does attempt to serve foreign importers, they would probably enter the site via the websites of the FERs or, in some instances, may even enter the site via the websites of the industry associations if they are focusing on industry-related information and suppliers. Alternatively, they could enter via the websites of the various ECs, IAs, or industry chambers (e.g. Chamber of Mines), or via the main NEP website. If they are interested in foreign country information, their first port of call might even be the websites of the dti’s FERs. These various routes into the NEP are depicted in figure 4 below.

4.15 Adopt a Federal Approach for the NEP

It is further recommended that the portal take a federal approach to information management, rather than a unitary or confederal approach. This suggests that, while the dti would take the lead in launching the portal and setting its strategy and that the portal would run primarily as a national portal, regional and industry partners would share in the dilution of the information to their respective constituents, and even as a source of information. Each of the stakeholders would have their own website and the information on the portal would be accessible via the stakeholders’ respective websites – a federal system (see figure 4).

Source: Authors’ own creation

4.16 Maintain and Update the NEP Daily

Both the exporter community and the export support community were adamant that the key to the success of the proposed portal would be well-maintained and up-to-date information. Maintaining information is often one of the biggest challenges of any website (McNamara 2018). Placing the NEP in the hands of a small management team that will focus on content generation, and maintenance should contribute to an up-to-date portal. In addition, making use of information partners and export experts to contribute information and to maintain that information will be an important part of the management of the portal. The underlying technology should facilitate this maintenance process by automatically identifying information that is older than a certain date. Information identified as ‘old’ would need to be certified as ‘reviewed and updated’ by a content manager or outside expert.

Up-to-date information will engender trust amongst the user (i.e. export) community, and this should contribute to reuse and word-of-mouth promotion. If a well-maintained portal is also linked to a real-time live (i.e. staffed by people) export helpdesk (as is currently available from the DTI) where exporters could call someone for assistance, these services will go a long way to ensuring the success of the NEP.

Content is clearly highly dynamic and needs to be updated constantly and adapted and expanded over time. The lack of the update of information was a key reason why the export community did not want the DTI (or any other government department) to run the portal because they felt that the DTI would not be competent to do so, and that update and maintenance of the portal should instead be left in the hands of either the private sector or organised commerce.

Not only does the content need to be updated regularly, but the content width and depth needs to be increased regularly. By ‘width’ is meant the range of topics covered by the content, and increasing width means constantly including new topics. By ‘depth’ is meant the extent of content related to a particular topic. In this last-mentioned instance, it is proposed that supporting each topic should be information related to:

- Key content to do with the topic;

- export guidelines and checklists that can assist exporters to complete or attend to the topic in question;

- networking information (i.e. pointers to individuals and organisations who can assist the exporter);

- a link that places the topic within the overall export value chain or export process (thus providing the exporter with contextualisation);

- cases and success stories (i.e. examples from which exporters could learn);

- frequently-asked questions (FAQs);

- news items related to the topic in questions;

- links to and from similar or related topics;

- articles from other sources (i.e. to provide alternative perspectives);

- mouseover explanations of key terms;

- graphical information (such as videos, diagrams, photographs, graphics and infographics) to aid in understanding;

- links to industry bodies or organised commerce that can assist with exporting;

- commentary by other exporters (i.e. to gain insight from the experience of others); and

- in-text links to supporting information and related services.

The proposed portal should be developed in such a way that the usage of the content can be tracked statistically. In this way, popular content (perhaps based on user reviews and/or ratings) as well as deficiencies in the content can be determined and adjusted accordingly. Feedback from FAQs and even from user surveys can also be used to fine-tune the content to meet exporter needs better. The study has provided a good starting point, but the proposed framework is not an end-in-itself. It is therefore recommended that the starting content as identified in this study be improved upon and fine-tuned using input from the actual users of the portal over time.

5. Conclusion

This study in the South African context, draws on the extensive literature and research on export promotion and combines this literature with an empirical study that incorporates the views of South African exporters and the local export support community, to propose a framework for an NEP for the country. In this article, a framework is presented for how the NEP should be organised and the information it should include, as well as incorporating insights from the empirical data to propose how the portal should be developed (in respect of the information on offer, the management of the portal, the partners to the portal and the routes to the information). Although intended to provide a ‘roadmap’ for the development of a South African NEP, the findings, the authors suggest, are just as relevant for other countries planning to implement or redevelop their own NEPs.

References

- Ali, Q., Shaikh, M., Shah, A.B. and Shaikh, F.M., 2017. Relationship between export and economic growth in Pakistan by using OLS technique. International Journal of Case Studies, 6(4), p.22.

- Audier, N., 2007. National export strategy. Presentation of the Department of Trade and Industry, Pretoria, 2007.

- Belloc, M., and Di Maio, M., 2011. Survey of the literature on successful strategies and practices for export promotion by developing countries. Working paper, International Growth Centre, June 2011.

- Cateora, P.R., Graham, J. and Gilly, M.C., 2019. International Marketing. 18th Edition. New York, USA: McGraw Hill.

- Chuvakin, V., 2007. Some aspects of internet portal market competition. Unpublished DPhil thesis, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook.

- Cross, P., 2016. The importance of international trade to the Canadian economy: An overview. Article published in the Fraser Institute Research Bulletin, October 2016.

- Cuyvers, L., and Viviers, W., 2012. Export promotion: A decision support model approach. South Africa: SUN MeDIA METRO.

- Double, Z., 2005. Up to standard? Containerisation International, November: 89. [online] Available at: http://www.inttra.com/home/Assets/News/News_156.pdf [Accessed on 11 March 2021].

- Gouws, A., and Moore, A., 2012. National Exporter Development Plan. Project report prepared on behalf of the DTI, September. [online] Available at: http://www.dti.gov.za/DownloadFileAction?id=745[Accessed on 11 March 2021].

- Gouws, A., 2015. Series of personal interviews, January-December 2015 in Pretoria.

- International Trade Centre, 2004. TPO best practices: Strengthening the delivery of trade support services. Geneva: International Trade Centre, United Nations Council on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and World Trade Organisation (WTO).

- International Trade Centre, 2003. Trade Portal Tool. An electronic checklist developed by the International Trade Centre Geneva, United Nations Council on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and World Trade Organisation (WTO).

- Lahtinen, H., and Rannikko, H., 2018. Study on best practices on national export promotion activities. The European Economic and Social Committee (EESC), September 2018.

- Lederman, D., Olarreaga, M. and Payton, L., 2009. Export promotion agencies revisited. Policy research working paper no. 5125, November 2009. [online] Available at: http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/pdf/10.1596/1813-9450-5125 [Accessed on 11 March 2021].

- Lederman, D., Olarreaga, M. and Payton, L., 2010. Export promotion agencies: Do they work?. Journal of Development Economics, 91(2), pp.257-265.

- Mabuyane, O., 2019. Address by the Executive Mayor of Buffalo City Metro. Eastern Cape Export Symposium on 27 March 2019. [online] Available at: https://www.ecexportsymposium.co.za/opening-address [Accessed on 11 March 2021].

- McNamara, S., 2018. The importance of updating your website. [online] Available at: https://medium.com/@Sionaainn/the-importance-of-updating-your-website-49c9468ff731[Accessed on 11 March 2021].

- Shihab, R.A., and Abdul-Khaliq, T.S.S., 2014. The causal relationship between exports and economic growth in Jordan. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 5(3), pp.203–208.

- United States Department of Commerce, 2014. The role of exports in the United States economy. [online] Available at: http://trade.gov/neinext/role-of-exports-in-us-economy.pdf [Accessed on 11 March 2021].

- Yuzawa, S., 2012. Practical measures of export promotion: Experience at JETRO and EEPC [online] Available at: https://www.grips.ac.jp/forum/af-growth/support_ethiopia/document/2012.01_ET/Mr.Yuzawa_Practical_WEB.pdf [Accessed on 11 March 2021].

Websites reviewed in the study

| Portal | Acronym | Web address* |

| Australia Trade and Investment Commission | AUSTRADE | https://www.austrade.gov.au |

| Bulgaria Small and Medium Enterprises Promotion Agency | BSMEPA | https://export.government.bg |

| Department for International Trade United Kingdom Trade and Investment (UKTI) | DIT | https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/ department-for-international-trade* http://www.ukti.gov.uk |

| Enterprise Singapore International Enterprise Singapore (IES) | ES | https://www.enterprisesg.gov.sg* http://iesingaport.gov.sg |

| Export Canada | EC | https://www.canada.ca/en/services/ business/trade/export.html |

| Enterprise Ireland | EI | https://www.enterprise-ireland.com |

| Jamaica Investment Promotion Jamaica Trade and Investment (JTI) | JAMPRO | https://dobsinessjamaica.com/trade* http://www.jamiacatradeandinvestment.org |

| Kenya Export Promotion and branding Agency Export Promotion Council Kenya (EPC) | BRAND.KE | https://brand.ke* http://epckenya.org |

| Malaysia External Trade Development Corporation | MATRADE | http://www.matrade.gov.my |

| New Zealand Trade and Enterprise | NZTE | https://www.nzte.govt.nz |

| Uganda Export Promotion Board | UEPB | http://ugandaexports.go.ug* http://ugandaexportsonline.com |

| International Trade Administration (USA) | ITA | https://www.trade.gov |

*Some of the export portals have changed their web address and or name since the study. Their latest web name/web address is provided in the table, with the previous name/web address provided below in italics.

Article Rights and License

© 2021 The Authors. Published by Sprint Investify. ISSN 2359-7712. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.