Keywordshigher education marketing international education international students study abroad word-of-mouth communication

JEL Classification M31

Full Article

1. Introduction

Participating in an education program abroad is not a habitual decision a student makes daily. Not only they need to adjust to unfamiliar academic and cultural realms (Chirkov et al., 2007), they also need to face issues pertaining in the post-covid 19 era. Recent research suggests that international students are more prone to feeling lonely compared to local students (Neto, 2021). This will be inevitably exacerbated by the restrictions during the pandemic that discourage people to gather in a large group. Indeed, prior to the pandemic, friendship groups with compatriots were found to be helpful for international students to understand the local culture and norms (Woolf, 2007).

Even before the pandemic, education’s offering was heterogeneous and intangible (Pimpa, 2005). From the students’ and their families’ point of view, this makes determining its investment return difficult. Considering the already high risk (Pimpa, 2005), Fischer (2020) expressed her concern that parents will be hesitant to allow their children to study abroad during this pandemic. Therefore, it is conceivable to believe that international students receive considerable inputs from their social surroundings when making a decision to study abroad. Indeed, interpersonal influence has been noted as a major factor in industries of which offerings are intangible (Mourali et al., 2005)

Word-of-mouth communication, referred as WOMC hereafter, and its importance in marketing have been well documented over the past several decades (Harrison-Walker, 2001). WOMC literatures (e.g. Bansal and Voyer, 2000; Ha and Lee, 2018) argued that the communication method is more meaningful in the service sectors since the risks associated with a purchase in the sector is considerably higher. Over the last decade, studies on WOMC have been dominated by online WOMC in which customers find reviews or online discussions about certain products (e.g. Jiménez-Castillo and Sánchez-Fernández, 2019; Lee et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2020), with the so-called digital influencers dominating its discussion.

WOMC has also been a fruitful topic in the higher education (HE) marketing sector. Mazzarol and Soutar’s (2002) work highlighted the importance of recommendation from peers and relatives when choosing a destination to study abroad. Akin to the service sector in general, recent works on WOMC in HE marketing, such as those conducted by Le et al. (2019), Perera et al. (2020) and Yang and Mutum (2015), are also dominated by online WOMC.

However, crucially, the studies mentioned above focused on WOMC that prospective students received during the university selection process. International students, meanwhile, go through a prior yet more pivotal decision making before choosing which university to attend. They first have to form an intention that they actually want to study abroad as opposed to studying locally. The Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1985) provides a suitable ground to distinguish intention from actual behavior in this research. While the actual behavior can mean a student’s act to apply in their selected school, intention forming stage refers to the time during which the students are still deciding to study abroad.

More importantly, intention provides a better measure in assessing one’s attitude towards something compared to the actual behavior. Indeed, factors such as “dependance on others” (Ajzen, 1985, p.28) as well as unpredictable situational context (Peter and Olson, 2009) can hinder someone in turning their intention into the actual behavior. These factors are prevalent during this pandemic. Prospective international students might possess an intention to study abroad but travel restriction or parents’ disapproval may prevent them to study abroad.

Therefore, this research will focus its endeavor on identifying the WOMC that prospective international students receive during the intention-forming stage. The purpose of this study is to identify the WOMC that prospective international students receive when they are deciding to get involved in an international education program. As aforementioned, WOMC studies in international HE have largely focused on the university selection phase during which their intentions are more concrete. However, prospective international students might be more susceptible to the WOMC that they receive during the intention forming stage as their attitude towards international education might not be as strong as during the university selection phase.

This study sought to identify that WOMC and how, or if, it has influenced their attitude towards studying globally. International students possibly have different attitudes towards WOM when it comes to studying abroad since international education offers lifelong benefit that is still felt way beyond graduation (Forsey et al., 2012). It is distinct with, for instance, in the streaming service which benefits are somewhat limited to the period of the subscription.

Adding a point previously inferred, the intention forming stage refers to the period of time during which the students had already had an intention to study internationally but they had not explicitly shown an effort to search for information and alternatives. This study sought to identify the WOMC that they received during this exact stage. Therefore, unlike Le’s et al. (2019) and Yang and Mutum’s (2015) works, this study will not focus on the WOM that prospective students receive during the later stages. Indeed, Bearden et al. (1989) asserted that an individual’s susceptibility to other individuals’ inputs is multidimensional in nature, so it is recommendable to conduct a study focused on a particular stage.

2. Literature Review

2.1. WOM Communication and Higher Education Marketing

Word-of-mouth Communication (WOMC) has been heralded as a wide-reaching, effective and credible marketing communication (Özdemir et al., 2016; Patti and Chen, 2009). WOM is particularly useful in the service sector since the offerings are intangible so it is difficult to judge the perceived risk associated with the purchase (Bansal and Voyer, 2000). The higher education sector is a beneficiary of WOMC since the sector’s offerings are credence of which ROI is difficult to predict (Patti and Chen, 2009).

Further, Bansal and Voyer (2000) argued that WOM’s strength is influenced by two factors, namely interpersonal and non-interpersonal factors. Interpersonal factors include the tie-strength between the WOM receiver and giver and the degree to which the WOM is actively sought. Non-interpersonal factors refer to the receiver’s and sender’s expertise as well as the receiver’s perceived risks. Their conception has been crucial to WOM literatures. Recently, the formulation is studied in E-WOM settings (e.g. Le et al., 2020; Yang and Mutum, 2015; Zhang et al.,, 2020). It is interesting to examine the prevalence of the tie strength factor (the relationship between the WOM sender and receiver) in E-WOM as the parties involved might be anonymous. While Zhang et al. (2020) found that interpersonal closeness is influential to purchase intention, Yang and Mutum (2015) noticed that the sender’s expertise is more decisive than the interpersonal ties with the senders. For the current study, tie strength is particularly relevant if the WOM sender is someone whom the receiver did not personally know prior to their WOM seeking activity. Indeed, international students often consult to those outside of their immediate surroundings for study abroad advice (Maulana, 2020).

Another crucial WOM definition specifically important to this study is related to the underlying motive on which the sender is giving WOM. It is argued that WOM is a form of communication involving no commercial intent (Patti and Chen, 2009). This aspect rules out a number of potential sources whom international students might see them as capable of giving informed inputs. For example, studies have shown that prospective international students often turn to international student agents (Zhang and Hagedorn, 2011) or prospective professors (Maulana, 2020). However, since it is hard to imagine that international student agents and prospective professors have no commercial intent at all when giving suggestions to future students, these groups are not considered as WOM resources.

2.2. Intention

Connecting someone to their future behavior (Peter and Olson, 2009), intention is defined as a point at which someone decides to start a set of actions to perform a behavior. While intention is a less concrete phenomena as opposed to behavior (Nasir, 2015), intention is arguably more telling when it comes to assessing someone’s attitude on an object. Therefore, understanding one’s intention towards something is pivotal, and, at the same time, challenging.

Theory of Planned behavior (Ajzen, 1985), one among many theories examining the distinction between intention and behavior, believes that intention evolves over time. Kim and Lawrence (2021) further argued that intention is the number of efforts that an individual plans to perform. Therefore, external circumstances, either perceived or real, often become a hindrance for the execution of behavioral intention.

Indeed, even before the start of the pandemic, Kim and Lawrence (2021) have noticed that there are reoccurring disparities between students who claim to intent to study abroad and those who actually study abroad. The plummeted number of enrolling international students during this pandemic has been well reported (Baer and Martel, 2020). However, that number only represents those who perform the actual behavior (studying abroad). That number fails to capture prospective international students who intent to study abroad but external circumstances prevent them to do so. This urges international student market researchers to understand behavioral intention more thoroughly. Therefore, the current study is focused on the word-of-mouth inputs that prospective international students receive during the intention stage and not during the later stages.

3. Research Method

This research is qualitative and employed interviews to meet the research objectives. Ten international students enrolled in various graduate degree programs at a mid-size university in the United States of America were involved as the respondents. The ten international students come from various cultural backgrounds; this was purposively done to aid the representability of international students in general, as such is the suggested measure in such a qualitative study (Susila, 2016).

This study focused on graduate program students since they might consider more variables when deciding to undertake a graduate education abroad including inputs from their social surroundings. Most graduate students start graduate programs after spending some time in their professional careers. Therefore, compared to undergraduate students, they might have received more WOMC when they were deciding to go abroad to study.

3.1. The Respondents

Opposed to Pope’s et al. (2014) inquiry which researched American students studying outbound, this study researched international students who were enrolled in graduate programs in the USA. Contrastive to Maringe and Carter (2007) and Pimpa (2003b, 2003a, 2005) who focused on international students from certain countries, this study included students from various countries in the world, as displayed by table 1.

To make sure that the respondents remained anonymous and felt free to express their stories, they were given a chance to pick random names for themselves. The data-collection stage mainly focused on the word-of-mouth that they received when they were deciding to enroll in their then current study programs. Therefore, the study was not discussing another program that they were planning to join in the future.

Table 1. The Respondents

| No | Random names | Home country | Program | Previously graduated abroad? |

| 1 | Amara | India | Master | No |

| 2 | Dann | China | Master | Yes, undergraduate |

| 3 | Halim | Pakistan | Master | No |

| 4 | Han | China | Master | Yes, undergraduate |

| 5 | Jessie | Germany | Master | No |

| 6 | Jake | India | Master | No |

| 7 | Tony | Cameroon | PhD | Yes, undergraduate and master’s |

| 8 | Amy | China | PhD | Yes, master’s |

| 9 | Soma | Saudi Arabia | PhD | Yes, undergraduate and master’s |

| 10 | Maria | India | PhD | No |

It is important to distinguish that this study refers international students as those who held a US student visa (either J or F visa) during their enrollment in the programs. A student whose origin is outside of the USA but possessed a US green card or citizenship was excluded from this research.

Table 1 also suggests the previous involvement in a degree seeking program outside of their home countries. As elaborated further in the discussion section, international experience was identified as a major variable in their attitudes towards WOMC.

4. Research Results

As aforementioned, the respondents of this study were purposively selected to represent the varied international student backgrounds in terms of their culture, social surrounding and nationality. As such, generality became a challenge in drawing noteworthy conclusions from the data-collection process. The following points are several insights that can be drawn from the respondents’ inputs.

4.1. Variations in the WOM Seeking Behaviors and the Susceptibility

When it comes to selecting which university to attend, recent studies conducted by Le et al. (2019, 2020) and Yang and Mutum (2015) found that WOMC is a decisive variable for prospective students. Yang and Mutum (2015) even went on to urge higher education institutions (HEIs) to build strong ties with their alumni to facilitate the growth of positive WOM.

However, this study crucially differs with those studies on two different fronts. Firstly, those studies were not conducted in international education settings. Secondly, the studies above were focused on the university selection process, which is a much later stage in the students’ journey in enrolling in an academic program. This study, meanwhile, zeroed in on WOMC that international students received during the intention forming stage, a much earlier stage in the journey.

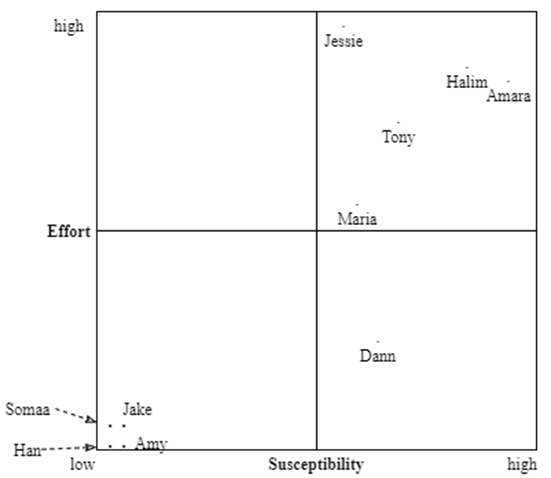

This study, therefore, found differing WOM seeking behavior patterns among the international students. While the previous studies almost unanimously concluded that the students used WOMC that they receive in making their decision (Le et al., 2020, 2019; Yang and Mutum, 2015), this study found that that is not always the case. Figure 1 is a helpful visual representation of the degree of each student’s susceptibility to WOM (horizontal axis) and their effort to seek WOMC inputs (vertical axis). It should be noted that this study only employed qualitative methods, so the basis of the figure is solely from the researcher’s interpretation.

Figure 1. the respondents’ WOMC seeking behavior and their susceptibility

Generally, students who graduated overseas showed less effort to seek WOM as well as lower susceptibility if they get WOM input. As suggested by table 2, there were 5 students who earned at least one of their previous degrees abroad. On the bottom left quadrant, Somaa, Han and Amy, have all earned at least one of their degrees abroad. These students showed little to no effort to seek WOMC input, and when they did receive WOMC, they suggested that those suggestions had little to not influence on their intention.

Table 2. respondents who have graduated abroad

| No | Student | Previous degree abroad |

| 1 | Amy | USA – master’s degree |

| 2 | Dann | Scotland – undergraduate degree |

| 3 | Han | USA – undergraduate degree |

| 4 | Somaa | USA – undergraduate and master’s degrees |

| 5 | Tony | Bangladesh – undergraduate and master’s degrees |

Dann did not actively seek input when deciding to study in the USA again after he attained his undergraduate degree in the country. However, he recounted that his father, a successful international businessman, recommended him to pursue his MBA in the USA since his father encountered a lot of striving businessmen/women who possess an MBA degree. He also conveyed how he randomly found a video online suggesting the auspicious expected financial ROI from an MBA degree. While he felt that he already knew what he was getting from an MBA degree earned in an American institution, he concurred that those WOMCs that he received earlier in the process strengthened his intention.

Tony earned both his undergraduate and master’s degrees abroad. However, he was concerned that academic demands in developed countries such as the USA would be more challenging than those he encountered in Bangladesh. It urged him to seek inputs from his social surroundings whom he felt have expertise and experience.

4.2. Friends and Relatives who Study or Graduated Abroad as the Most Influential WOMC Givers

As shown in figure 1, this study identified five students who actively sought WOMC and were susceptible to the inputs that they received during the intention-forming stage. Each of these students listed a friend or a relative who were studying or have graduated abroad as an important WOMC source, as further elaborated by table 3.

Table 3. WOMC received by the respondents

| No | Student | Cited friends / relatives | WOMC received |

| 1 | Amara | Brother who graduated and lived in the USA | Guided her from the beginning all the way through her arrival in the USA |

| 2 | Halim | Sister who graduated and lived in the USA | Told him to pursue master’s education in the USA instead of in the home country |

| 3 | Maria | Seniors in undergraduate who applied for PhDs in the USA her work supervisor who has a PhD | They helped her narrowing down her options and told her the social demands of living in the USA |

| 4 | Jessie | A high school friend who studied and lived in the USA | They told her what living in another country would bring and feel like |

| 5 | Tony | His master’s professor who got his PhD from Canada His undergraduate classmates who pursued further education abroad | They told him that he got all the qualities needed to have successful PhD experience in a developed country |

Moreover, Dann was the only student involved in the study who admitted to have been influenced by an online WOM when it comes to deciding to study abroad, as it has been mentioned in the previous subsection. It means that when they did actively seek WOM, prospective international students preponderantly turned to those closest to them to find suggestions when making a decision to study abroad.

4.2. Prospective Professors as an Input Source

Two students, Maria and Tony, intensively corresponded with their then prospective professors. While Tony talked to the professor because he wanted to be in the professor’s milieu, Maria’s communication with the prospective professors includes addressing the challenges of studying abroad.

This finding needs not be reported for two reasons. Firstly, this study was focused on the intention forming phase while the aforementioned inputs received by Tony and Maria were mostly during the later stages. Secondly and more importantly, as elaborated in the literature review, professors should not be considered as WOM sources since they might have commercial intent when giving suggestions to future students.

However, neither Tony or Maria seemed to realize, nor did it seemed they cared, that the prospective professors might have commercial intents. Therefore, it can be suggested that professors may have a unique position compared to other parties involved in the student recruitment. They are in a strategic position when it comes to student recruitment as they are seen more like role models or figures to turn to rather than marketers. Therefore, they have the potential to be even more impactful in recruiting new students.

5. Discussion

This study produced some opposing findings with those of Yang and Mutum (2015). Not all respondents in this research sought WOMC when they were deciding to study abroad. There is a couple of explanations to what has brought about this variation. Firstly, the students involved in this study are graduate students. Graduate students tend to have higher level of independence. For instance, Han repeatedly mentioned that he felt trapped in a “career gap” and wanted to study abroad to find more opportunities. Indeed, some students argued that they know what they were getting from postgraduate education and how it could help them professionally. Secondly, Yang and Mutum’s (2015) research was conducted on the context of university selection. This study, however, focused on identifying the WOMC that the respondents received in the earlier stage of the process during which they were still deciding to study abroad or not.

This study, in opposite, largely confirms Bansal and Voyer’s (2000) assertion. They argued that the higher the perceived risk of a purchase, the higher the probability of someone seeking for WOM inputs. Since this research involves prospective international students who were deciding to go on a global journey of which outcome might change their lives, there was monumental perceived risk involved and so they would be eager to find suggestions through WOMC. Those who have graduated abroad, however, have gone through an international education experience before so they perceived lower risks compared to those novice international students. Therefore, they felt less need to reach out to others for considerations.

Also in line to Bansal and Voyer’s (2000) conclusion, the students also sought WOMC sources who are perceived to possess expertise power. Friends and relatives who study abroad were found to be the most dominant WOMC source. Alumni has been heralded as a predominant WOM source in higher education marketing context as they are seen as an “insider” (Yang and Mutum, 2015, p.9). Bruce and Edgington (2008) who studied MBA alumni behaviors in giving WOM have found that the WOM that they give is far more than mere recommendation or discouragement to enroll. Alumni will also share the financial benefits and professional as well as personal gains that a student will get from a degree.

The findings also suggest that those closest to the students are the preponderant WOMC source. Indeed, tie strength with WOMC senders is an influential factor when seeking inputs from the social surrounding (Bansal and Voyer, 2000). “Social links”, the number of friends or relatives who are in the host country, often hold a key role in international students decision making (Mazzarol and Soutar, 2002, p.86). It is even suggested that these families and friends cast superior influence compared to education agent recruiters although the latter logically have stronger expertise power than the former (Mazzarol and Soutar, 2002). Culture also dictates how they seek for WOM sources (Özturgut, 2013). Most respondents in this study who sought WOM come from the same country or speak the same language.

Moreover, interestingly, this study only found one student who was exposed to online WOMC. Another student even refused to read online reviews because she was only willing to listen to her family members’ input. This is stark contrast with findings from recent literatures who asserted the strength of online WOM (Le et al., 2020, 2019; Yang and Mutum, 2015). This particular finding, in opposite, resonates better with older WOMC views by Bansal and Voyer (2000) and Mazzarol and Soutar (2002) who mentioned the people closest to the WOM recipients as the most powerful referrents.

This research also concludes that the international students who graduated abroad were less inclined to seek WOMC inputs. This is noteworthy since Bansal and Voyer (2000) viewed that the relationship between a WOM recipient’s expertise and their inclination to seek WOM resembles an inverted U relationship. According to Bansal’s logic, students who possess moderate understanding of the demands posed by international education would show more willingness to seek WOM source compared to students who have either low or high understanding of the matter. This research employs qualitative method, so to assess the expertise of the students who previously graduated abroad was unattainable. Therefore, there was little way to judge on which end of the inverted U these students’ expertise lie.

6. Conclusion

The findings of this study reaffirm Bansal and Voyer’s (2000) idea on WOM communication. Firstly, since international education is an investment of which return is uncertain, it increases the risk associated with it. This accordingly adds the likelihood of prospective international students seeking WOMC inputs. Secondly, however, students who have been abroad before are less likely to seek WOM inputs. Indeed, Bansal and Voyer (2000) have noted that the more perceived expertise power the WOM seekers possess, the less likely they actively seek WOM inputs.

Thirdly, this study found that friends or relatives who have studied abroad are a major source of WOMC. They are both personally close to the students and are perceived to have expertise power. It means that during the intention forming stage, international students do not have a plethora of WOMC sources as they mainly rely on those personally closest to them. It also means, however, that most students involved in this study did not turn to E-WOM inputs when deciding to study abroad. This opposes recent WOMC studies which show the strength of online word-of-mouth (e.g. Le et al., 2019; Yang and Mutum, 2015).

This inclination towards their immediate social surrounding as opposed to online strangers provides valuable managerial insights for higher education marketers seeking to attract prospective international students’ interests. The fact that the most prevalent WOMC source, as this study found, is friends or relatives who have studied abroad suggests that providing prime quality education service and experience will provide twofold benefits for the institution. Not only it will satisfy their current students, it will also enlarge the prospective international students pool as their current students can invite their close friends or families who previously do not intent to study abroad.

Moreover, this finding also suggests that universities can focus their online presence for prospective international students who have passed the intention forming stage. For instance, instead of writing lengthy blog-posts about the benefits of studying overseas, universities can instead show how their education offerings differ compared to other institutions’. Indeed, future international students who have progressed beyond the intention forming stages pay more attention on specific details such as a university’s course offering and future career prospects (Le et al., 2020).

Few studies have attempted to investigate the word-of-mouth communication that prospective international students receive when they are deciding to go abroad. This study offers insights on how these WOM communications are sought and which students are susceptible to the inputs. Further studies are encouraged to employ quantitative study to test the generality of this finding. It also behooves future inquiries to measure the effect of the WOMC that they receive during the intention forming stage. It is interesting to see if the WOMC that they have received in the earlier stages will transcend into the next stages or is limited in the earlier stages’ ambit.

Finally, while this study was able to meet its objective and provide some managerial insights, it possesses some inevitable limitations. While employing qualitative approaches provided deep understanding on the students’ attitudes on WOMC, it was done so by sacrificing generalizability. Other international students in other parts of the world might have differing views compared to the ones reported here. Moreover, this study was conducted long before the world was certain of the extent to which the COVID-19 pandemic alters the international education industry. With the changes as well as the innovation surrounding international education since the turn of the decades, this study might have yielded a different result had this study been conducted a few years after the start of the pandemic.

---

Acknowledgements: The author is particularly grateful to University of Dayton for their generous support in this research

Funding: This research was funded by Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta.

Conflicts of Interest: The author state that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ajzen, I., 1985. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In: J. Kuhl and J. Beckmann, eds. Action Control: from Cognition to Behavior. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.pp.11–39.

- Baer, J. and Martel, M., 2020. Fall 2020 International Student Enrollment Snapshot.

- Bansal, H.S. and Voyer, P.A., 2000. Word-of-Mouth Processes within a Services Purchase Decision Context. Journal of Service Research, 3 (2), pp.166–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/109467050032005

- Bearden, W.O., Netemeyer, R.G. and Teel, J.E., 1989. Measurement of consumer susceptibility to interpersonal influence. Journal of Consumer Research, 15 (4), pp.463–481.

- Bruce, G. and Edgington, R., 2008. Factors influencing word-of-mouth recommendations by MBA students: An examination of school quality, educational outcomes, and value of the MBA. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 18 (1), pp.79–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841240802100303

- Chirkov, V., Vansteenkiste, M., Tao, R. and Lynch, M., 2007. The role of self-determined motivation and goals for study abroad in the adaptation of international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 31 (2), pp.199–222.

- Fischer, K., 2020. Confronting the seismic impact of covid-19: The need for research. Journal of International Students, 10(2), pp. i-ii. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v10i2.2134.

- Forsey, M., Broomhall, S. and Davis, J., 2012. Broadening the mind? Australian student reflections on the experience of overseas study. Journal of Studies in International Education, 16 (2), pp.128–139.

- Ha, E.Y. and Lee, H., 2018. Projecting service quality: The effects of social media reviews on service perception. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 69, pp.132–141.

- Harrison-Walker, L.J., 2001. The Measurement of Word-of-Mouth Communication and an Investigation of Service Quality and Customer Commitment As Potential Antecedents. Journal of Service Research, 4 (1), pp.60–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/109467050141006.

- Jiménez-Castillo, D. and Sánchez-Fernández, R., 2019. The role of digital influencers in brand recommendation: Examining their impact on engagement, expected value and purchase intention. International Journal of Information Management, 49, pp.366–376.

- Kim, H.S. and Lawrence, J.H. 2021. Who Studies Abroad? Understanding the Impact of Intent on Participation. Research in Higher Education, 62(7), pp. 1039-1085. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-021-09629-9

- Le, T.D., Dobele, A.R. and Robinson, L.J., 2019. Information sought by prospective students from social media electronic word-of-mouth during the university choice process. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 41 (1), pp.18–34.

- Le, T.D., Robinson, L.J. and Dobele, A.R., 2020. Understanding high school students use of choice factors and word-of-mouth information sources in university selection. Studies in Higher Education, 45 (4), pp.808–818. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1564259

- Lee, D., Ng, P.M.L. and Bogomolova, S., 2020. The impact of university brand identification and eWOM behaviour on students’ psychological well-being: a multi-group analysis among active and passive social media users. Journal of Marketing Management, 36 (3–4), pp.384–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2019.1702082

- Maringe, F. and Carter, S., 2007. International students’ motivations for studying in UK HE: Insights into the choice and decision making of African students. International Journal of Educational Management, 21 (6), pp.459–475.

- Maulana, H., 2020. Relevant Others: Identifying the Reference Groups of International Students in the USA. Journal of Nonprofit and Public Sector Marketing. pp. 1-24 . https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2020.1798858.

- Mazzarol, T. and Soutar, G.N., 2002. ‘Push-pull’ factors influencing international student destination choice. International Journal of Educational Management, 16 (2), pp.82–90.

- Mourali, M., Laroche, M. and Pons, F., 2005. Individualistic orientation and consumer susceptibility to interpersonal influence. Journal of Services Marketing, 19 (3), pp.164–173.

- Nasir, M., 2015. Analisis pendekatan internal dan eksternal konsumen terhadap keputusan pembelian produk batik di kampoeng batik laweyan surakarta. Benefit: Jurnal Manajemen dan Bisnis, 19 (1), pp.1–11.

- Neto, F., 2021. Loneliness among African international students in Portugal. Journal of International Students, 11(2). [online]. Available at: https://www.ojed.org/index.php/jis/article/view/1379 [Accessed 24 February 2021].

- Özdemir, A., Tozlu, E., Şen, E. and Ateşoğlu, H., 2016. Analyses of Word-of-mouth Communication and its Effect on Students’ University Preferences. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 235, pp.22–35.

- Özturgut, O., 2013. Best practices in recruiting and retaining international students in the U.S. Current Issues in Education, 16(2).

- Patti, C.H. and Chen, C.H., 2009. Types of word-of-mouth messages: Information search and credence-based services. Journal of Promotion Management, 15 (3), pp.357–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496490903185760.

- Perera, C.H., Nayak, R. and Nguyen, L.T. Van., 2020. The impact of subjective norms, eWOM and perceived brand credibility on brand equity: application to the higher education sector. International Journal of Educational Management, 35 (1), pp.63–74.

- Peter, P. and Olson, J., 2009. Consumer Behavior and Marketing. Ninth ed. New York: McGaw-Hill.

- Pimpa, N., 2003a. The influence of family on Thai students’ choices of international education. International Journal of Educational Management, 17 (5), pp.211–219.

- Pimpa, N., 2003b. The Influence of Peers and Student Recruitment Agencies on Thai Students’ Choices of International Education. Journal of Studies in International Education, 7 (2), pp.178–192.

- Pimpa, N., 2005. A family affair: The effect of family on Thai students’ choices of international education. Higher Education, 49, pp.431–448.

- Pope, J.A., Sánchez, C.M., Lehnert, K. and Schmid, A.S., 2014. Why Do Gen Y Students Study Abroad? Individual Growth and the Intent to Study Abroad. Journal of Teaching in International Business, 25, pp. 97–118.

- Silva, M.J. de B., Farias, S.A. de, Grigg, M.K. and Barbosa, M. de L. de A., 2020. Online Engagement and the Role of Digital Influencers in Product Endorsement on Instagram. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 19 (2), pp.133–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332667.2019.1664872.

- Susila, I., 2016. Pendekatan kualitatif untuk riset pemasaran dan pengukuran kinerja bisnis. Benefit: Jurnal Manajemen dan Bisnis, 1 (1), pp.12–23. [online]. Available at: https://journals.ums.ac.id/index.php/benefit/article/view/1413 [Accessed 7 December 2021].

- Woolf, M., 2007. Impossible Things Before Breakfast: Myths in Education Abroad. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11 (3–4), pp.496–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307304186

- Yang, H.-P. (Sophie) and Mutum, D.S., 2015. Electronic Word-of-Mouth for University Selection. Journal of General Management, 40 (4), pp.23–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/030630701504000403

- Zhang, H., Liang, X. and Qi, C., 2021. Investigating the impact of interpersonal closeness and social status on electronic word-of-mouth effectiveness. Journal of Business Research, 130, pp.453-461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.020

- Zhang, Y. and Hagedorn, L.S., 2011. College Application with or without Assistance of an Education Agent: Experience of International Chinese Undergraduates in the US. Journal of College Admission, n212, pp.6-16. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ939061

Article Rights and License

© 2022 The Author. Published by Sprint Investify. ISSN 2359-7712. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.